![]()

E. B. Gareth Jones, Kevin D. Hyde and Ka-Lai Pang

1 Introduction

Why do we need a book on freshwater fungi? Within the last decade a number of books on freshwater fungi have been published: Freshwater Mycology (Tsui and Hyde 2003) and Genera of Freshwater Fungi (Cai et al. 2006), or reviews (Wong et al. 1998; Shearer et al. 2007; Wurzbacher et al. 2010, 2012). Most texts on freshwater fungi however, deal with specific or ecological groups, e.g. Ascomycota, chytrids, fungal diseases, ultrastructure of ascospore appendages (Barr 1980; Wong et al. 1999; Shearer and Raja 2010). Thus, none gives the overall picture of the diversity to be found in freshwater habitats. Such vital groups of organisms as Pythium/Phytophthora are rarely considered. Many reviews do not include up to date data or ignore certain taxonomic groups (yeasts) or habitats (peat swamp fungi). Freshwater yeast populations have been almost ignored, despite the fact that they are common in aquatic systems (Hagler and Ahearn 1987; Gadanho and Sampaio 2004; Libkind et al. 2010; Fell et al. 2011). There is no overall estimate of the number of freshwater fungi. Jones (2011) undertook such a review of marine fungi which concluded that present day estimates were way out. So what of the estimates of freshwater fungi? This lack of an overall picture of freshwater mycology led Wurzbacher et al. (2010, 2012) to conclude that research on freshwater fungi is much neglected.

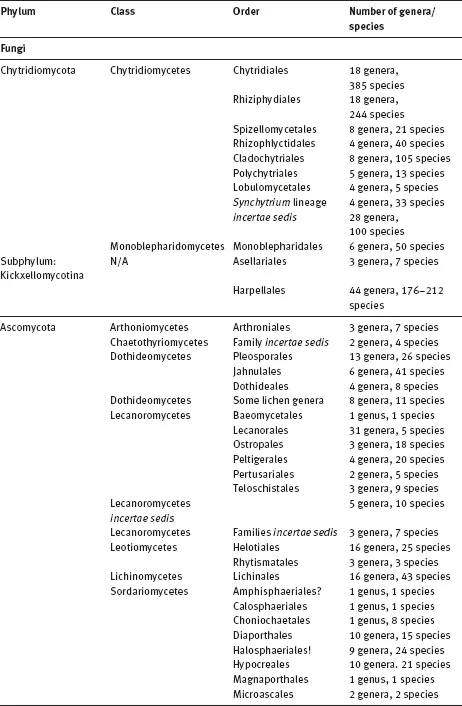

Freshwater fungi with unusual branched conidia were reported in the 1890s (Saccardo and Therry 1880; de Wildeman 1884, 1893, 1895; Rostrup 1894) with descriptions of the taxa: Heliscus lugdunensis, Tetracladium marchalianum, T. maxilliformis, Clavariopsis aquatica and Anguillospora longissima (as Fusarium longissimum), but it was not until the early 1940s that it was appreciated that these fungi formed a unique community on senescent leaves in streams and rivers (Ingold 1942, 1944). Since then there has been a steady stream of papers reporting on their occurrence from all over the world (Nawawi 1985; Goh and Hyde 1996). Ingold also drew attention to the existence of abundant ascomycetes in temperate freshwater habitats (Ingold 1951, 1955), while Hyde highlighted their occurrence in tropical locations: Australia (Hyde 1992), the Philippines (Hyde and Wong 2000) and Hong Kong (Tsui et al. 2001). The early 1850s saw the first report of chytrids in freshwater habitats (Braun 1856) which lead to the publication of the book on Aquatic Phycomycetes (Sparrow 1960). These early studies culminated in a wealth of data on freshwater fungi as can be seen from the list of taxa in Tab. 1.1, with particular major revisions in their taxonomy in the period 1990–2013(Shearer 2010; Kurtzman et al. 2011; Powell and Letcher 2012).

Studies of freshwater fungi and fungal-like organisms to date have largely been morphological with sequence data used to help resolve phylogenetic relationships. These studies are largely surveys of different taxonomical or ecological groups with few focusing on an all taxa inventory (Bärlocher 2007; Wurzbacher et al. 2010, 2012).

Tab. 1.1: Classification and estimate of numbers of freshwater fungi and fungal-like organisms.

Complied with data from FWA data base; Martha Powell; Sally Glocking; Robert Lichtwardt; Lei Cai; and data presented in various chapters in this volume.

Neubert et al. (2006) undertook a molecular survey of fungal diversity of the phanerogam Phragmites australis and identified 350 distinct operational taxonomic units (OTU). Many were fungal species yet to be identified and similar observations have been made on chytrids in sediments (Luo et al. 2004; Slapeta et al. 2005).

In this introductory chapter, we consider some of the general concepts that apply to all groups of freshwater fungi and fungal-like organisms. They include the composition of major groups and their origin, numbers of species and their distribution. Finally we discuss the organization of this volume and the contents of each major section. Chapters are written by specialists in the field of freshwater mycology and incorporate the latest published data.

1.1 Origin of freshwater fungi and fungal-like organisms

Freshwater fungi may have their origins in the sea while others are migrants from terrestrial habitats (Vijaykrishna et al. 2006; Beakes and Sekimoto 2009; Beakes et al. 2012). Keeling (2009) opined that the stramenopiles form a monophyletic clade with the alveolates as a sister group and evolved some 570 million years ago (mya). All osmotrophic stramenopiles are thought to have originated in the sea and migrated into freshwater as nematodes and insect larvae became terrestrial (Beakes et al. 2012).

Fungi may also have evolved in the sea and migrated into freshwater, e.g. the chytrids Rozella (Beakes and Sekimoto 2009; Lara et al. 2009; Jones et al. 2011) and subsequently became terrestrial. Bass et al. (2003) recovered novel lineages of chytrids from environmental DNA from marine ecosystems, supporting the marine affinities of primitive chytrids. Vijaykrishna et al. (2006) were of the opinion that freshwater ascomycetes evolved from terrestrial fungi probably circa 390 mya.

1.2 Classification of freshwater fungi

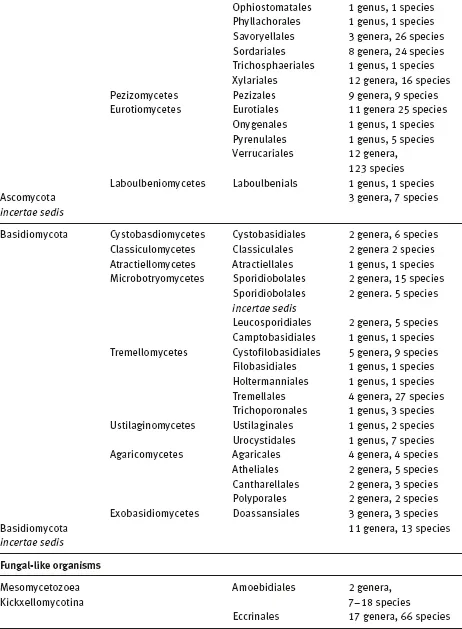

Jones et al. (2009) published a classification of marine fungi, but nothing similar is available for freshwater fungi with exception of the Fresh Water Ascomycetes (FWA) Database for the Ascomycota (http://fungi.life.illinois.edu/). Hibbett et al. (2007) list six phyla in the Kingdom Fungi, of which four have freshwater representatives: Chytridiomycota, Blastocladiomycota, Ascomycota and Basidiomycota (Tab. 1.2). Estimates of the number of freshwater species are given in Tabs. 1.1 and 1.2, but these are conservative as such lists are not available for many of the groups. For example: there is little data on the number of aquatic Mortierellales, Mucorales or Kickxellales.

The most specious phylum is the Ascomycota with freshwater representatives in 33 orders (622 species and excluding ascomycetous yeasts), while other taxa remain to be referred to orders, e.g. asexual taxa total 531 (Fallah and Shearer 2013) most of these with sexual stages in the Ascomycota (Tab. 1.2). Two orders of the Dothideomycetes support common freshwater fungi: Pleosporales and Jahnulales, the former comprises primarily terrestrial forms, while the Jahnulales is a novel lineage in the phylum with both freshwater and marine species (Suetrong et al. 2011; Zhang et al. 2012). The discomycetes are represented by two orders: Helotiales (16 genera, 25 species) which has many asexual morph connections, and the Rhytismatales which has primarily taxa that are found on leaves of terrestrial plants. Fourteen orders in the Sordariomycetes have freshwater members, with the Microascales (Halosphaeriaceae) and Savoryellales comprising both marine and freshwater taxa (Jones et al. 2009; Boonyuen et al. 2011). The Pezizomycetes and Laboulbeniomycetes are represented by the orders Pezizales and Laboulbeniales, respectively. The order Eurotiales and Verrucariales are members of the phylum Eurotiomycetes, with the lichen order accounting for 13 genera and 123 species, the most speciose genus in the Ascomycota. Cai et al. (See Chapter 3) put the number of freshwater ascomycetes as 622 while in Tab. 1.1 we calculate there are 556, which we regard as a conservative estimate. Many asexual morphs belong in the ascomycetes and are not counted in this table (Jones et al. 2008; Shearer et al. 2009; Hu et al. 2012).

Tab. 1.2: Estimates of freshwater fungi and fungal-like organisms.

| Group | Number of species |

| Ascomycota | 622 |

| Basidiomycota (not yeasts) | 41 |

| Chytridiomycota | 500–1,289 |

| Asexual taxa | 531 |

| Trichomycetes | 183 |

| Basidiomycota yeasts | 74 |

| Peat swamp fungi | 317+ |

| Fungi on Phragmites litter | 600 |

| Lichens | 270 |

| Predacious fungi | 40 (200?) |

| Endophytes | 40? |

| Oomycota | 49–87 |

| Total | 3,069–4,145 |

Freshwater Basidiomycota are represented by 19 orders and comprise many yeasts and asexual morphs whose phylogenetic relationships are not fully resolved. Although a few produce fruiting bodies visible to the naked eye, most occur as single cells (yeasts) or as variously branched conidia (See Chapter 4). One hundred and fifteen taxa have been attributed to the Basidiomycota (in 50 genera), the most numerous referred to Tremellales (27 species) and Sporidiobiales (20 species).

The Chytridiomycota may appear well represented by 611 freshwater species, in 103 genera, however, not all these species are to be found in freshwater habitats as many occur as parasites of terrestrial plants and animals, as long as there is a film of water for the development and dispersal of their zoospores. The taxonomical placement of many of these taxa is supported by molecular data. The final phylum is the Blastocladiomycota, a group previously assigned to the Chytridiomycota.

The fungal-like organisms, Straminipila, are represented by the orders Leptomitales, Saprolegniales (Saprolegniomycetes), Rhipidiales and Peronosporales (Peronosporomycetes). With the exception of the Saprolegniales, most taxa referred to these orders are terrestrial and do not occur in fully aquatic habitats (Beakes et al. 2013).

1.3 Estimated number of freshwater fungi

Estimates of freshwater fungi are perfunctory as they do not include all taxa and how the data is calculated not often known, but the figures generally quoted are: 622 species (170 genera) ascomycetes (Cai et al., Chapter 3); more than 531 named hyphomycetes, 226 species (55 genera); trichomycetes (which includes three orders no longer regarded as fungi), while the basidiomycetes and zygomycetes are poorly documented (Misra and Lichwardt 2000; Tsui and Hyde 2003). Shearer et al. (2007) opine there are circa 500 ascomycetes, 405 asexual morphs, aero-aquatic 90, and no basidiomycetes are mentioned, other groups they include are 576 chytrids and 138 members of the Saprolegniales (fungal-like organisms), but no figure for freshwater yeasts (Shearer et al. 2007). Wurzbacher et al. (2011) indicate there are 2,535 freshwater fungi, which include ascomycetes, asexual morphs (which predominate), four basidomycetes (as aero-aquatic fungi), and 200 lichenized fungi. Jones and Pang (2013) estimated the nu...