eBook - ePub

Contrasting English and German Grammar

An Introduction to Syntax and Semantics

- 327 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Contrasting English and German Grammar

An Introduction to Syntax and Semantics

About this book

This book offers an introduction to the derivation of meaning that is accessible and worked out to facilite an understanding of key issues in compositional semantics. The syntactic background offered is generative, the major semantic tool used is set theory. These tools are applied step-by-step to develop essential interface topics and a selection of prominent contrastive topics with material from English and German.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Contrasting English and German Grammar by Sigrid Beck,Remus Gergel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Languages. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Structure and Meaning: An Introduction to Syntax and Semantics

dp n="14" folio="" ? dp n="15" folio="" ?Chapter I-1 Introduction to the field: Syntax and semantics

No matter what you do, somebody always imputes

meaning into your books.

meaning into your books.

(Dr. Seuss)

We give a short introduction to the field of linguistics in section 1. We explain what linguists mean by a grammar. In section 2 we introduce the components of the grammar that we investigate in this book: syntax and semantics, the study of sentence structure and sentence meaning. Sections 3 and 4 give a short preview of the book and its first part, respectively. Further readings are suggested in section 5.

1. The scientific study of language

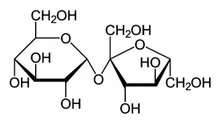

Linguists study language and languages, like biologists study life and living organisms, and chemists study the structure and behavior of matter. The scientific study of language develops a formal or mathematical model of language. This model mirrors the properties of language in those respects that are under investigation. This is parallel to the way the natural sciences work. Chemistry, for example, has developed a model of substances that associates them with molecular structures. The chemical structure for sugar is given in Figure 1:

Fig. 1. Structure of sucrose also known as sugar1

This formula is not related in a very obvious way to how you normally encounter sugar: it’s white grainy stuff, it tastes sweet, you put it in your tea, you buy it by the kilogram and it is relatively inexpensive. Why do chemists associate it with the above formula? Because it allows them to explain the properties and behavior of sugar: that it dissolves in water, how it can be produced or reduced and so on. The formula does have something to do with your everyday experience of sugar (you wouldn’t put it in your tea if it didn’t dissolve), but it is pretty abstract. And it is at most very indirectly related to how sugar is sold and how much it costs.

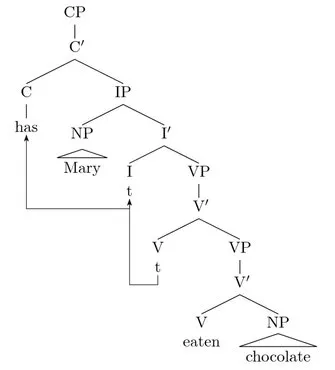

Similarly, linguists associate the sentence in (1) with the structure in (2):

- (1) Has Mary eaten chocolate?

- (2)

Here, also, the relation between your everyday experience of such a sentence and the model developed in the scientific study of the phenomenon is rather abstract. You would normally hear such a sentence as a sequence of sound waves. It would be produced by someone interested in communication, and it might convey emotion (outrage, perhaps). The representation in (2) has something to do with your everyday experience (it is related to a sequence of sound waves by representing a sequence of words). But it is at most very indirectly related to the communicative needs and emotional states of someone who utters (1).

Why do linguists associate the sentence with the structural representation? Because it allows us to explain the properties and behavior of the sentence and the elements contained in it. Linguistics, like other sciences, aims to provide models that make falsifiable predictions. For example, the fact that the question expressed in (1) cannot be expressed as in (3) follows from the representation in (2). The model also helps us to understand why English today cannot form the question in (4), although it once could, and has to use (5) instead; why (6) is word salad; and so on.

- (3) Eaten Mary has chocolate?

- (4) Ate Mary chocolate?

- (5) Did Mary eat chocolate?

- (6) Has Mary likes the linguist who been to Samoa?

Like the chemists’ formal model of substances, the linguists’ formal model of linguistic expressions allows us to explain the properties and behavior of the area under investigation. In our case, this is basically what you know when you know a language. For example, what is the knowledge that you possess which makes you accept (1) and (5), but reject (3), (4) and (6)? How do you know what (1) means? Relatedly, how was the knowledge of someone who accepted structures like (4) different from yours? Why were structures like (6) never accepted in the history of English or (as far as we know) in any other language? What information allows a child learning a language to acquire this kind of knowledge?

In short, linguists model knowledge of language. This textbook is an introduction to the scientific study of language in the sense of developing a formal model of knowledge of language.

This way of studying language scientifically is something many people encounter late in life or not at all. Most people are more familiar with the study of language as it is pursued in traditional grammars. Typically, in such a grammar you are told in a language that you have already mastered about a different language that you have probably not mastered. To stick with our example, you might consult a German grammar book about how to phrase questions that are answered by “yes” or “no. “ You might find the example in (7) as an illustration together with the information that it means the same as English (1).

- (7) Hat Maria Schokolade gegessen?

This is certainly helpful for the traveller and the language student. But notice how it does not model knowledge of language. It transfers your knowledge of English by way of analogy to another language. It presupposes a large part of what the linguist still wants to explain. For example: What is a question? How do (1) and (7) come to express a question? Moreover, there is an interesting difference between (1) and (7): in (7), the verbal participle gegessen ‘eaten’ follows the object Schokolade ‘chocolate’, while it’s the other way around in (1). Further examples would reveal a parallel effect. What is the systematic source of this difference? How is the knowledge that a German speaker posseses different from the knowledge that an English speaker has to produce this effect? Native speakers have this knowledge. But they are not aware of it: a native speaker’s knowledge of the rules of language is subconscious. Linguistics brings this subconscious knowledge to light. (As a possible analogy, consider bats, w...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Table of Contents

- Part I - Structure and Meaning: An Introduction to Syntax and Semantics

- Part II - Extending the Theory and Applying it to Crosslinguistic Differences

- References

- Index