- 246 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

There is no written grammar of Colloquial Israeli Hebrew whatsoever. This book is the first written grammar of the spontaneous language spoken in Israel that describes Colloquial Israeli Hebrew from a synchronic point of view, and that is not a text book based on normative Hebrew rules.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Colloquial Israeli Hebrew by Nurit Dekel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Communication Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Israeli Hebrew – an introduction

In this chapter Israeli Hebrew is defined and presented, as well as grammar and description books written on Israeli Hebrew and/or Modern Hebrew.

As of December 2012 (CBS 2013), Colloquial Israeli Hebrew, elsewhere also referred to as Modern Hebrew, is spoken among 7,984,500 Israeli residents within the state of Israel, out of whom 4,378,000 are native speakers, and the rest are either bilingual, or speak Israeli Hebrew as a second language. According to various, unofficial, estimates, Israeli Hebrew is also the native language of over half a million speakers, living outside Israel. Slight linguistic differences can be observed between different populations of Israeli Hebrew speakers ; such differences can be noted in some vocabulary items, phonological features (specifically intonation), and perhaps some syntactic features. Yet, these differences altogether are assumably insufficient to determine separate dialects, and Israeli Hebrew is considered a language with no dialectal variances (Hoffman 2004:193, Glinert 1989 [2004]:2, Coffin-Amir & Bolozky 2005:31, Weninger 2011:524).

1.1 Hebrew, Modern Hebrew, Israeli Hebrew, Israeli, and in-between

Most people refer to Israeli Hebrew simply as Hebrew. Hebrew is a broad term, which includes Hebrew as it was spoken and written in different periods of time, and according to most of the researchers as it is spoken and written in Israel and elsewhere today.

Several names have been proposed for the language spoken in Israel nowadays, Modern Hebrew is the most common one, addressing the latest spoken language variety in Israel (Berman 1978, Sáenz-Badillos 1993:269, Coffin-Amir & Bolozky 2005, Schwarzwald 2009:61). The emergence of a new language in Palestine at the end of the nineteenth century was associated with debates regarding the characteristics of that language. Some scholars supported the direction of the language by normative approaches. It was finally decided to use, as much as possible, the grammar of Biblical Hebrew as the basis of the new language variety, with some components based on Mishnaic Hebrew. The instruction of Hebrew language in schools was strict and completely followed the normative approach (Sáenz-Badillos 1993:272-273).

Not all scholars supported the term Modern Hebrew for the new language. Rosén (1977:17) rejected the term Modern Hebrew, since linguistically, he claimed that ‘modern’ should represent a linguistic entity, which should command autonomy towards everything which preceded it, while this was not the case in the new emerging language. He also rejected the term Neo-Hebrew, because the prefix ‘neo’ had been previously used for Mishnaic and Medieval Hebrew (ibid, p. 15-16); additionally, he rejected the term Spoken Hebrew as one of the possible proposals (ibid, p. 18). Rosén supported the term Israeli Hebrew, as in his opinion it represented the non-chronological nature of Hebrew, as well as its territorial independence (ibid, p. 18). Rosén then adopted the term Contemporary Hebrew from Téne (1968) for its neutrality, and suggested the broadening of this term to Contemporary Israeli Hebrew (ibid, p. 19).

After the Second World War the language spoken in Israel became standardized. This standard is believed to be taught in Hebrew schools today in Israel and elsewhere.

In 2006, the term Israeli was proposed by Zuckermann (2006, 2008), to represent both the multiple origins of the language spoken in Israel, and the territory where it is mostly spoken. Zuckermann (2006) argues that what he labels Israeli is a hybrid language containing elements both from Semitic and from Indo-European languages as its building blocks, and following Wexler’s approach (1990), he thinks that it is not a direct, purely genetic, subsidiary of earlier Hebrew forms. He claims that there were two main contributors to the establishment of this language, which were Yiddish and Hebrew in its earlier forms. He suggests that secondary contributors were also involved in the process, and these were European languages and Arabic (Zuckermann 2006:58-59). Zuckermann claims that morphological forms of Israeli are Hebrew, and thus Semitic, whereas its syntax and phonology, including syllable structure and intonation, are European (2006:60-61).

Even today there is no consensus about how to name the language spoken in Israel. As demonstrated above, most of the researchers are dedicated to the Hebrew origins of the language, and therefore use a naming convention that includes the term Hebrew. I believe that the adoption and use of the term Hebrew originally represented a much wider range of views and intentions rather than just linguistic considerations. I believe that the term Israeli is more adequate to represent the language spoken in Israel without involving nonlinguistic considerations; yet, I follow Rosén’s terminology herein (1977:18) and use the term Israeli Hebrew, since it is more common among most researchers. Since the colloquial language, spontaneously spoken in Israel, is discussed herein, I am also using the term colloquial Israeli Hebrew.

Being natural and spontaneous, and fundamentally different from Hebrew, Israeli Hebrew often does not follow the Normative Hebrew rules; it has an independent, unique, structure, which is different from that of Hebrew. In general, similarly to European languages, Israeli Hebrew is characterized by a more analytical structure, whereas Hebrew is characterized by a more synthetic structure. This book presents the structure of spontaneously spoken Israeli Hebrew.

1.2 Grammar books

Several grammar books are available on Modern Hebrew, reviewing its structure, from different points of view: Berman 1978, Glinert 1989 [2004], 1994, Schwarzwald 2001, Coffin-Amir & Bolozky 2005. There is no unified structure to these books, each of them discusses different phenomena from a different point of view. Also, all of them pre-suppose that Modern Hebrew is a modern variety of Hebrew, and therefore all these descriptions are based upon and compared with Hebrew normative rules. They do share some characteristics: all of them present a bulk of examples from various Hebrew layers and registers, some of which include spoken phrases, others are only written norms; and all of them use transliteration rather than actual phonetic transcription. Apart from Berman (1978) that partially relies on real data collected among children, these grammars are not based on any substantial data, but rather on the authors’ impressions and assumptions. Borochovsky-Bar-Aba (2010) describes widespread phenomena in spoken Israeli Hebrew, but calls it ‘a description’ rather than ‘a grammar.’ She uses authentic examples from different registers and styles, including formal circumstances, such as court speech and the media, which are not purely spontaneous. In addition to these, text books are available (Blau 1967, 1975, Antebi 2008, Berkovich 2008), mainly for school students, presenting normative Hebrew grammar. None of these grammar books refers to colloquial Israeli Hebrew only; Borochovsky-Bar-Aba (2010) declares referring to spoken Hebrew, including all kinds of spoken data which are not spontaneous.

In this book, I describe colloquial Israeli Hebrew, which is the daily spontaneous spoken language only.

1.3 The research corpus

This book describes colloquial Israeli Hebrew, which is the daily spontaneous spoken language in Israel. Only spontaneous speech is described; no formal speech is referred to whatsoever.

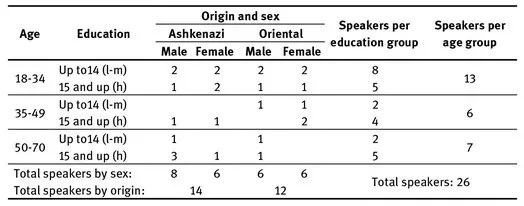

The corpus consists of over 50,000 words from over 50 native speakers of Israeli Hebrew, collected between 2005-2013. The corpus was built according to the reports of the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics (ICBS 2013), and demographically corresponds to the Israeli population, as presented hereafter.

The research was performed on Israeli Hebrew native speakers exclusively. A corpus of more than 50,000 words was established for that purpose. The recorded conversations included at least 8 minutes of speech per each speaker. According to measurements performed prior to 2009 for a preliminary pilot research (Dekel 2009a), continuous speech of 8 minutes contains at least 1000 words of the tested speaker, including conjunctions, and excluding truncated words, unclear speech and chunks of laughter. These 8 minutes of recordings also contain the speech of the speaker’s conversation mates, in a similar quantity of words, i.e. about 1000 additional words, that were not uttered by the speaker. These 1000 additional words were also collected from all the recordings. For each speaker, there was at least one additional conversation mate.

The research corpus includes Israeli Hebrew native speakers exclusively, that are not bilingual, to avoid the interference of other native languages. Only spontaneous conversations were used for the analyses that were recorded independently by the author; these conversations were held in a wide variety of contexts and situations. The research group included Israeli citizens and residents, native speakers of Israeli Hebrew, in different cross-sections. Non-native speakers were excluded from this research, in order to determine the basic language rules among Israeli Hebrew native speakers only. Also, this research did not include minority groups such as Arabs, Druze, and others, who use Israeli Hebrew as a second language. These populations usually live in areas where Arabic is the first spoken language, and their contact with Israelis is unlike that of other groups of Hebrew speakers, such as new immigrants, who are scattered among the Israeli population. The group of conversation mates includes at least 26 additional speakers from the informants’ surroundings, who actively took part in the conversations. The demographic distribution of the population is based upon the reports of the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics (ICBS 2013), and includes Israeli Hebrew native speakers, males and females, ages 16 and up, from different backgrounds, origins, and educational levels.

Table 1-1: Distribution of the main informants in the research corpus according to cross-sections

The conversations were manually transcribed and annotated by the author. Transcriptions and annotations were done according to the audio files containing the conversations, using the programs PRAAT and CoolTalk for the phonetic, phonological and prosodic analyses. After the corpus was fully transcribed and annotated, all the data were inserted into a database computer file, where they could be easily filtered and analyzed according to different criteria. The data were then sorted according to the relevant tags and analyzed to obtain the regularity of that tag.

The corpus was divided into speech units (SUs) rather than into sentences. Since discourse contains units, which are not sentences, the latter are irrelevant to analyze spontaneous speech. For an explanation on speech units and the division guidelines, see chapter 5: Syntax.

2 Israeli Hebrew phonology

In this chapter the phonological structure of Israeli Hebrew is presented. The following phonological characteristics of Israeli Hebrew are discussed and illustrated with examples: phonological inventory, phonological rules, consonant clusters, syllable structure, stress.

2.1 Phonological inventory

The phonological inventory of Israeli Hebrew phonemes is presented in Tables 2-1 and 2-2 below, showing consonants, then vowels, respectively. IPA symbols are used to represent the phonemes1.

It is important to bear in mind that any reference to phonological entities herein,...

Table of contents

- Colloquial Israeli Hebrew

- Trends in Linguistics Studies and Monographs

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1 Israeli Hebrew – an introduction

- 2 Israeli Hebrew phonology

- 3 Israeli Hebrew morphology

- 4 Parts of speech

- 5 Syntax

- 6 The correlation between form and meaning

- 7 Discourse structure in Israeli Hebrew

- 8 Appendices

- 9 Bibliography

- Index