![]()

1 Introduction

The typological phenomenon of non-expressed subject pronouns has constituted a major research topic in the generative literature and as such has provided an empirical basis for the Principle and Parameters approach to generative syntax (Chomsky 1981, 1986, 1993, 1995, Chomsky & Lasnik 1993). Since the seminal work of Perlmutter (1971), a two-fold major distinction between languages has been maintained: on the one hand, languages allowing for non-expressed subject pronouns, so-called null subject or pro drop languages, and, on the other, languages not allowing for non-expressed subject pronouns, referred to as non-null subject or non-pro drop languages.

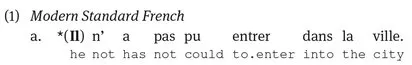

In Modern Standard French, subject pronouns are generally expressed in finite clauses, unless the subject is expressed by a non-pronominal DP or by a pronoun other than a subject pronoun.

‘He could not enter the city.’

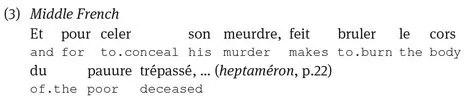

‘And to conceal his murder, he has the body of the poor dead man burnt.’

This stage of French has therefore usually been analyzed as a non-null subject language.

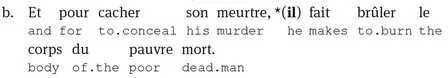

In Old French (9th-13th centuries) and Middle French (14th-16th centuries), on the contrary, subject pronouns are not consistently expressed in these contexts, as illustrated in (2) and (3) by the Medieval French equivalents of the Modern Standard French sentences in (1).

dp n="12" folio="2" ? ‘He could not enter the city;’

‘And to conceal his murder, he has the body of the poor deceased burnt, …’

The medieval stages of French are therefore generally analyzed as null subject languages. Still, these stages of French differ considerably from modern Romance null subject languages such as Italian and Spanish in the possibility of non-expressed subject pronouns. Specifically, Old and Middle French show characteristics reminiscent of non-null subject rather than null subject languages.

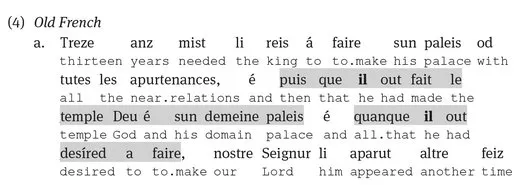

In Italian and Spanish, considered prototypical null subject languages in the generative literature, the expression of referential subject pronouns usually follows from specific semantico-pragmatic reasons such as emphasis or contrast. In the absence of such reasons, i.e. in cases of an extremely high degree of antecedent accessibility (Givón 1983, Ariel 1990), these pronouns are generally non-expressed, and this independently of the clause type. In Old and Middle French, however, referential subject pronouns are frequently expressed when their antecedent is extremely highly accessible (Morf 1878, Foulet 1928, Franzén 1939, Price 1966, Vanelli, Renzi & Benincà 1985, Roberts 1993, Vance 1997). What is more, these stages of French stand out due to a root-embedded-asymmetry, in that these pronouns are considerably more frequently expressed in embedded than in root clauses (Morf 1878, Foulet 1928, Franzén 1939, Wagner 1974a, b, Vanelli, Renzi & Benincà 1985, Adams 1987a, b, c, Roberts 1993, Vance 1997). These characteristic traits of the medieval stages of French are illustrated in (4) by means of a comparison of an extract from a 12th century French prose text with its Italian and Spanish equivalents.

‘The king needed thirteen years to build his palace together with his near relations, and when he had built the temple of the Lord and his own palace and all what he had desired to do, the Lord appeared to him another time, just as He had done at Gibeon.’

In contrast to Italian and Spanish in which for reasons of an extremely high degree of antecedent accessibility, the third person singular masculine referential subject pronoun is consistently non-expressed in the relevant embedded clauses, this pronoun is invariably expressed in the Old French source text. Crucially, this non-restriction of the expression of referential subject pronouns to contexts of emphasis or contrast as well as the frequent expression of these pronouns in embedded clauses results in an overall high frequency of expressed referentials in Old and Middle French.

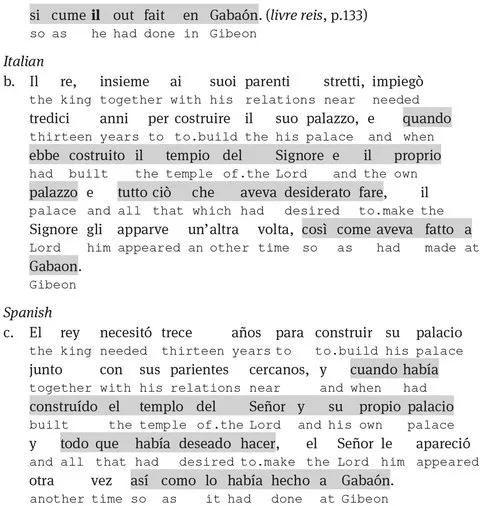

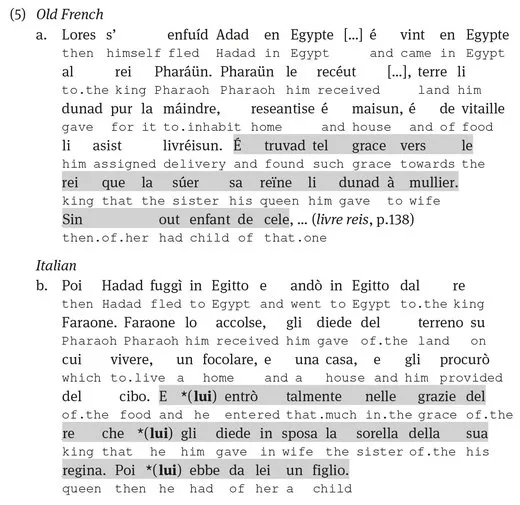

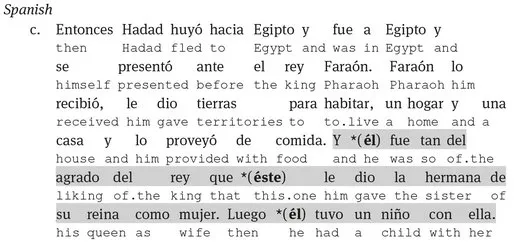

dp n="14" folio="4" ? This inclination for the expression of referential subject pronouns notwithstanding, the medieval stages of French also allow for the non-expression of these pronouns in contexts of emphasis or contrast (Etienne 1895, Franzén 1939, Price 1966, Sandqvist 1976, Schøsler 1988, Jensen 1990, Buridant 2007), i.e. in the very contexts to which the expression of these pronouns is generally restricted in modern Romance null subject languages such as Italian and Spanish. This is illustrated in (5), again by means of a comparison of an extract from a 12th century French prose text with its Italian and Spanish equivalents.

dp n="15" folio="5" ? ‘Then Hadad fled to Egypt […] and went to Egypt to the King Pharaoh. Pharaoh received him, gave him land to inhabit, a home, and a house, and provided food for him. And he [= Hadad] found such favor with the king that he [= the King Pharaoh] gave him the sister of his queen in marriage. Then he [= Hadad] had a child from her, …’

In contrast to Italian and Spanish in which the third person singular masculine referential subject pronoun is consistently expressed in the relevant clauses to avoid ambiguity, given that the subject of these clauses is different from the subject of the preceding clause(s), this pronoun is invariably non-expressed in the Old French source text. In this regard, then, Old and Middle French differ again from modern Romance null subject languages.

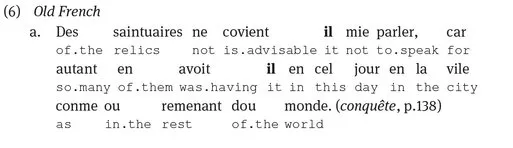

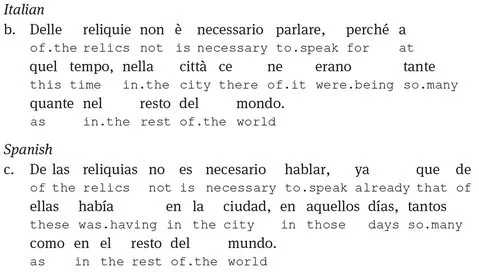

A final and fundamental contrast between the medieval stages of French and modern Romance null subject languages such as Italian and Spanish is that only the former allow for the expression of subject pronouns in impersonal constructions, while the latter have these pronouns consistently non-expressed in such constructions. This is illustrated in (6) by means of a comparison of an extract from a 13th century French prose text with its Italian and Spanish equivalents.

‘Of the relics it is not necessary to speak, for there were as many of these in those days in the city as in the rest of the world.’

Crucially, expressed subject pronouns in impersonal constructions in Old and Middle French show the same distribution as expletive subject ...