eBook - ePub

The Directionality of (Inter)subjectification in the English Noun Phrase

Pathways of Change

- 324 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Directionality of (Inter)subjectification in the English Noun Phrase

Pathways of Change

About this book

The book investigates pathways of (inter)subjectification followed by prenominal elements in the English Noun Phrase, by tracing the development of identifying, noun-intensifying and subjective compound uses. By means of in-depth corpus study, the assumed unidirectionality of (inter)subjectification in the NP is verified and refined.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Directionality of (Inter)subjectification in the English Noun Phrase by Lobke Ghesquière in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sprachen & Linguistik & Sprachwissenschaft. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Synchrony

Not chaos-like together crush’d and bruis’d, But, as the world, harmoniously confused: Where order in variety we see, And where tho’ all things differ, all agree.

Alexander Pope – Windsor Forest

Chapter 1

A functional-cognitive model of the English NP

This study assumes a constructional approach such as developed in the cognitive-functional tradition (e.g. Langacker 1991, 2007; Croft 2001; Fried 2010). The notion of construction that I will work with is that of a layered organization of functions realized by structural dependency relations between the component units (Langacker 1991: 143–146). This chapter will introduce the different functions fulfilled by the constituent elements of the English NP as distinct form-meaning pairings. Chapter 2 will then focus on the structural make-up of the English NP, i.e. how the functional layers are symbolized by dependency structures of the modifier-head kind (Langacker 1991: 146). In the following sections of this chapter, the relevant functions will be discussed as distinct form-meaning pairings with special attention for their (inter)subjective character.

Traditional approaches to the NP have often been class-based, taking word class categories such as verb, adjective and noun as the starting point for the description. In such a class-based approach of which – partial –examples are found in Quirk et al. (1972, 1985), Bache (2000) and Crystal (2003), the English NP is described as built up of elements from the traditional word classes determiner, adjective and noun, which are typically associated with identification, attribution and categorization respectively. Such an account of English NP structure is, however, problematic in a number of respects. First, there is not a one-to-one match between the ‘established’ grammatical classes and the different functions an item can have in discourse. The head of the NP, for instance, can be realized as a simple noun (a bird) or a compound noun (a blackbird), but also by adjectives (the British) and pronouns (you). Similarly, the secondary determiner function can be realized by adjectives (a similar story), adverbs (the then president), numerals (the third album), quantifiers (all the men), etc. (see Breban, Davidse, and Ghesquière 2011: 2691; §1.4.2). Second, linguistic elements can undergo syntactic-semantic changes as a consequence of which they may not only shift function but also word class in some of their uses, i.e. display layering in the sense of Hopper and Traugott (2003:124; §3.2) (e.g. Adamson 2000; Denison 2006; Breban 2010a). A well-known case is very which, along with a functional shift from attribution (‘true’) to degree modification (‘to a high degree’), has shifted from adjective to adverb.

dp n="28" folio="14" ? It is clear that a class-based approach to the NP cannot fully account for the synchronic variation and diachronic change associated with it. As Croft (2001: 8) notes, “[l]anguage is fundamentally DYNAMIC, at both the micro-level – language use – and the macro-level – the broad sweep of grammatical changes that take generations to work themselves out” [emphasis original]. Any valid model of the English NP should be designed in such a way as to be able to account for this synchronic and diachronic dynamicity. Linguistic analysis of specific items must therefore always take into account differences – distributional, syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic –relative to their function in the discourse (Croft 2001: 73).

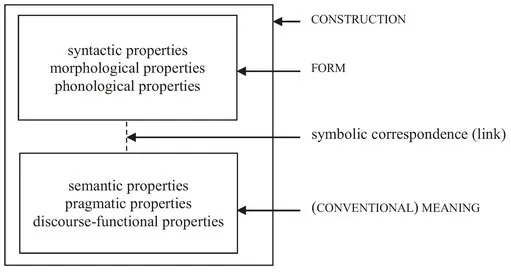

In this study it is assumed that a constructional approach of cognitive-functional orientation such as advocated by Croft (2001) is best suited to account for this. In such an approach, not grammatical classes as such, but constructions are the basic units of analysis. Constructions are conceived of here as functional structures in which grammar and lexis are integrated with each other, i.e. as distinct form-meaning pairings (Croft 2001; Fried 2010), as illustrated in Figure 1. Note that this reading of ‘construction’ comprises linguistic units of variable sizes ranging from morphemes to multi-word strings.

Figure 1. The symbolic structure of a construction (Croft 2001: 18)

As shown in Figure 1, taking a construction or functional structure as starting point for linguistic description does not preclude attention to syntactic characteristics. On the contrary, it allows linguists to attend to the full syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic diversity it displays, including scopal and collocational features.3 Grammatical categories and word classes are derived from and defined by the constructions in which they appear (Van Langendonck 1999; Croft 2001; see also Halliday [1961] 2002a). In a number of ways, cognitive-functional construction grammar incorporates, and further explicates, valuable elements from the functional tradition developed, amongst others, by Haas (1954), Firth (1959), Halliday (2002a), Matthews (1974) and linguists from the Prague school such as Danes (1964) (Fried, p.c.). Overall, the direction of linguistic description is from function to form, rather than from form to function.

The remainder of this chapter will be devoted to the development of a dynamic, functional model of the English NP that can account for the synchronically and diachronically dynamic nature of NP structure and its component elements both in terms of syntax and semantics.4 Point of departure will be existing functional models such as those proposed by Halliday (1994) and Bache (2000), and the cognitive model proposed by Langacker (1991).

1.1. The functional make-up of the English NP

1.1.1. Halliday’s structural-functional account

In Halliday’s (1985, 1994) view, the linguistic system encompasses three main functional-semantic components: the ideational, the interpersonal and the textual (see also Halliday and Hasan 1976: 26–27). First, the ideational component is concerned with representational semantics, with the expression of ‘content’. It offers the resources to describe referents. Second, the interpersonal component involves all speaker-hearer related meaning in language. All meanings related to the speech event and the deictic centre are interpersonal, as well as meanings reflecting the speaker’s personal attitudes toward, and evaluation of, what is being talked about. Third, the textual component covers all discourse-related meaning (given–new, theme–rheme, topic–focus, etc.), including cohesive elements.

Although interpersonal and textual meanings are to different degrees present in the NP, only the ideational component is, according to Halliday (1994: 190), necessary to develop an adequate functional model of NP structure. Importantly, the ideational component of language consists, in his view, of two subparts: the experiential, which is “more directly concerned with the representation of experience” and the logical, which “expresses the abstract logical relations which derive only indirectly from experience” (Halliday and Hasan 1976: 26). For the logical structure of the English NP, a dependency analysis is proposed in which the head and modifiers of the NP stand in a relation of recursive modification or subcategorization. In this univariate structure, all the elements of the NP are related by “the recurrence of the same function: α is modified by β, which is modified by γ, which is ...” (Halliday 1994: 193) (§2.1). The experiential structure, on the other hand, accounts for the distinct functions of the various component parts or constituents of the NP. It is conceived of not as a univariate but rather as a “multivariate structure”, i.e. “a constellation of elements each having a distinct function with respect to the whole” (Halliday 1994: 193). The remainder of this section will be devoted to a discussion of the NP on the basis of its experiential meaning, i.e. as an experiential constituency structure.5

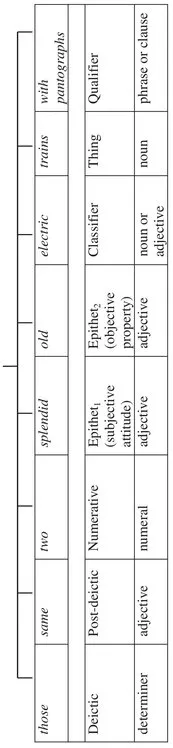

As an experiential structure, the English NP, “taken as a whole, has the function of specifying a class of things … and some category of membership within this class” (Halliday 1994: 180). Importantly, despite the misleading term ‘Thing’, the main function of the head of the NP is to denote the class or type of entity talked about, not a distinct entity. It is typically realized by common nouns, which “are precisely what their name implies, common to a class of referents” (Halliday 1985: 168). This class can be further subcategorized by one or more of the functional elements Deictic, Numerative, Epithet and Classifier. Finally, additional subcategorization can be expressed by post-modifiers, all captured under the functional label Qualifier. Halliday’s analysis of the experiential structure of the English NP is represented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The experiential structure of the English NP

The Thing is “the semantic core of the nominal group” (Halliday 1994: 189) and all other elements, both preceding and following, are claimed to further characterize the Thing. First, deictic elements indicate “whether or not some specific subset of the Thing is intended” (Halliday 1994: 181). If so, they characterize it either demonstratively, i.e. in terms of proximity (this, that, those, etc.), or by possession (my, your, his, etc.) (Halliday 1994: 181). Second, the Post-deictic, “adds further to the identification of the subset” “by referring to its fame or familiarity [regular, well-known, notorious, etc.], its status in the text [above, aforementioned, etc.], or its similarity /dissimilarity to some other designated subset [similar, same, different, etc.]” (Halliday 1994: 183). Third, Numeratives, subsuming amongst others ordinal and cardinal numbers, and relative and absolute quantifiers, “indicate some numerical feature of the subset” (Halliday 1994: 183). Fourth, Epithets indicate “some quality of the subset”, either an objective, potentially defining property (e.g. old, long, blue, fast) or an expression of the speaker’s subjective attitude (e.g. splendid, silly, fantastic) (Halliday 1994: 184).6 Fifth, the Classifier “indicates a particular subclass of the thing in question, e.g. electric trains, passenger trains, wooden trains, toy trains” (Hallida...

Table of contents

- Trends in Linguistics - Studies and Monographs 267

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgements

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables

- Table of Figures

- Introduction

- Part I - Synchrony

- Part II - Diachrony

- Part III - The case studies

- Summary - Towards a reconciliation of synchrony and diachrony

- References

- Subject index