1.1 A brief socio-linguistic history of Galician

The Galician language (Galego) is a Western Iberian Romance variety spoken primarily in the Spanish comunidad autónoma (autonomous community), or region of Galicia in the provinces of Pontevedra, A Coruña, Ourense, and Lugo. It is also spoken in the western portion of the Asturian autonomy (Principality of Asturias) in the areas to the west and east of the Eo and Navia rivers, in O Bierzo and As Portelas in the eastern portions of the Castilla-León autonomy, and in parts of the autonomy of Extremadura in areas such as Cáceres and Val de Xálima. Similar linguistic varieties are also spoken in parts of Portugal adjacent to Galician-speaking areas of Spain, including but not limited to the erstwhile northern Portuguese provinces of Tras-Os-Montes and Minho, which coincide with the contemporary distritos (districts) of Bragança, Vila Real, Braga, and Viana do Castelo. Galician also boasts diaspora communities within other parts of Spain (e.g. Catalunya), and abroad in Buenos Aires (Argentina), Montevideo (Uruguay), La Habana (Cuba), Caracas (Venezuela), and Mexico City (Mexico).

Following historical accounts (Freixeiro-Mato 1997; López Valcárcel 1991; Mariño Paz 1998; Monteagudo-Romero 1999), Galician and Portuguese were largely the same language – a language typically referred to as Galego-Portugués (Galician Portuguese) until around the 13th century. As evidenced in documents from the period, it was an everyday language among all social classes, and was the language of administrative, civil and ecclesiastical documents. It was also a literary language, and enjoyed prestige as a language of lyric poetry throughout the Iberian Peninsula. The political division of Portugal from present-day Galicia led to a differentiation of the two languages. Although the Galician language has enjoyed periods of resurgence from time to time over the years, including the present day, it has existed largely as a minority language for over five hundred years. Ramallo (2007) cites the thirteenth century as the origin of Spanish-Galician contact in Galicia, when the kingdom of Galicia became part of the Kingdom of Castile. Castilian Spanish gradually penetrated into Galicia, culminating in the sixteenth century with the installation of Castilian as the official language of the Kingdom of Castile and the disappearance of Galician from official documents (Monteagudo 1999). While Galician was still spoken in rural areas – arguably a domain in which it enjoys majority status – it was not until the second half of the nineteenth century that Galician enjoyed a renaissance as a language of culture. Galician continued on this trajectory until the end of the Spanish Civil War and the rise of the Francisco Franco regime (1939–1975), during which Galician suffered a public disappearance. While speakers of Galician were not as viciously persecuted as their Catalan and Basque counterparts (perhaps owing to the fact that Franco himself was from Galicia), Galician was strongly discouraged and stigmatized as a rural, uneducated, and uncivilized language. Urbanization and modernity arrived comparatively late in Galicia, and Spanish was seen as part of this modernity, thus leading to a gradual rise in bilingualism that left Galician relegated to serving as a chiefly rural and familial language. Since the fall of the Franco regime and the transition to democracy, the minority languages of Spain have been legalized, revitalized, and standardized (Siguán 1992), but Galician has not enjoyed the prestige of Basque or Catalan, owing principally to Galicia’s (comparatively) weaker economy. While all official minority languages co-exist with Spanish in situations of diglossia within the Spanish State, Galician differs in that Spanish is perceived to hold a high position of prestige in Galicia, while Galician is perceived to hold the low position. Galician is considered the language of the poorer, less-educated segment of society, while Spanish continues to be the language of social mobility and elite status (Murillo 1988; del Valle 2000).

According to Ethnologue (Lewis, Simons, and Fennig 2013) estimates, there were 3,170,000 speakers of Galician in 1986, and 3,185,000 speakers worldwide. According to 2001 (census) estimates, there were roughly 2.2 million speakers of Galician, 1.4 million of whom reported always speaking Galician, and 780,000 of whom reported speaking Galician occasionally. According to the Instituto Galego de Estatística (IGE, Galician Statistical Institute: www.ige.eu), the population of Galicia in 2009 was 2,796,089. Among those who were self-reported habitual speakers of Galician 779,297 reported always speaking Galician and 687,618 reported speaking more Galician than Spanish. Due to the differences in data collection methodologies behind these figures, which are complicated by population migrations in the region, it is difficult to determine if language use is in decline. In the following section, I discuss the sociolinguistic context of Galicia in greater detail.

1.2 The sociolinguistic situation in Galicia

According to the Ley Orgánica de Educación (Fundamental Law of Education), education within the Spanish state is free and compulsory from ages 6 to 16. The (re)establishment of Galician-language instruction in primary and secondary schools has been partly successful, as Del Valle (2000) reports that over 50% of speakers aged 16–25 speak only Spanish (17.7%), or more Spanish than Galician (35.7%). In 2007 the Galician Parliament issued a new decree (124/2007) requiring that a minimum of 50% of school instruction be conducted in Galician (Loureiro-Rodríguez 2009, but see also Regueira 2009 for a more in-depth history of the decree and reaction to it), a measure that was taken largely in order to address previous failures of compliance with laws in private schools and schools in urban areas (Ramallo 2007). According to Huguet (2004), linguistic normalization laws in the regional autonomies of Catalunya, Valencia, the Balearic Islands, Navarra, the Basque Country and Galicia are a response to a desire that students finish their years of compulsory education with a relatively balanced dominance of Spanish and the minority language in question. He argues that the result of bilingual education programs is that monolingual Basque (Euskera), Catalan or Galician speakers no longer exist, and that all native speakers of these languages also know and can use Spanish. In the subsections that follow, I will show statistical evidence suggesting that the majority of Galician speakers are also speakers of Spanish – especially among the younger segments of the population. This is of utmost importance with respect to the research detailed in this monograph, since many of the individuals who participated in the quantitative tasks that I describe in Chapter 3 reported being bilingual to greater or lesser degrees. It is also why I sought to determine participants’ native language in addition to their habitual language. In section 1.2.1, I discuss the bilingual situation in Galicia, presenting figures on self-reported native language and self-reported habitual language use. I also discuss how this situation relates to heritage-speaker phenomena such as attrition and incomplete acquisition. In section 1.2.2, I present figures on self-reported linguistic competence in Galicia, showing that those who claim to speak Galician to varying degrees report high levels of competence in both Spanish and Galician.

1.2.1 Heritage-speaker bilingualism in Galicia

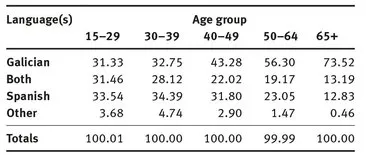

According to 2008 data reported by the Galician Statistical Institute in Table 1, 73.52% of Galicians older than 65 years of age surveyed, and 56.3% of Galicians between the ages of 50 and 64 surveyed reported having learned only Galician as their first language. For speakers younger than 50, these figures fall below 50%. Interestingly, however, younger age groups reported higher levels of exposure to both Galician and Spanish as a child. According to 2004 data gathered by the Mapa Sociolingüístico de Galicia (MSG, Sociolinguistic Map of Galicia) study (González, Rodríguez, Fernández, Loredo & Suárez 2007: 281), over 70% of those surveyed learned or acquired Galician in the family environment.

Table 1: Self-reported first language(s) percentages by age group in Galicia.

Source: Galician Statistical Institute (www.ige.eu). Santiago de Compostela, 2008.

Primary exposure to a minority language in a naturalistic setting such as the home is a typical hallmark of a heritage speaker of a language. Heritage speakers (see e.g. Montrul 2008; Rothman 2009 among numerous others) are adults who started as simultaneous bilinguals or child second language (L2) acquirers. Heritage speakers are native speakers of their first language (L1) in that they have acquired it naturalistically, but crucially, their L1 is not the dominant language of the society in which they live. The crucial factors involved in heritage language acquisition involve potential qualitative and quantitative differences in input, the influence of the societally dominant language, and difference in literacy aptitudes, potentially related to formal education in the heritage language. Typically, there is a distinct inequality between the support that the heritage language receives in the home, on the one hand, and the support that the dominant language possesses or receives in the community at large, on the other. In comparison with native monolinguals, the combination of these factors can result in what may be interpreted as either arrested development or language attrition.

Exposure to the societally-dominant L2 sets the stage for the onset of bilingualism. Sorace (2004) suggests that there is a direct association between incomplete learning and the onset of bilingualism as well as the onset of attrition. Montrul (2008) differentiates between incomplete L1 acquisition and L1 attrition as specific cases of intergenerational language loss. Montrul views L1 attrition as a phenomenon that can occur in childhood or adulthood. In attrition, a particular linguistic property that was mastered for some time with native-like proficiency is lost. For Montrul, incomplete acquisition happens in childhood when certain linguistic properties do not reach age-appropriate levels of proficiency due to intense exposure to the L2. Essentially, following childhood exposure, the L1 proficiency of the speaker fossilizes, or ceases to mature beyond a certain point as the individual matures. Although the definitions of these terms differ slightly, Montrul notes that they are not mutually exclusive concepts, as both may result simultaneously or even sequentially for any given linguistic property. There are also a variety of causes for which a certain property may not be acquired. For example, if a given property is lacking in the ambient input the child is exposed to, this can lead to incomplete acquisition. Rothman (2007) found that bilingual children who acquired Brazilian Portuguese in a purely naturalistic setting in the home but attended English-medium school did not acquire inflected infinitive forms. While one might interpret these results as suggestive that the consequence to not being exposed to schooling in a standard form of a language...