Aliens in Johannesburg: ‘District Six’ in international cinemas

In the year 1982, an alien spaceship appears over the South African city of Johannesburg. The extra-terrestrials are in a state of utter destitution, many of them dead, sick, or malnourished, and obviously unable to find their way home again. A camp is set up for these aliens just outside Johannesburg: District 9. In the decades that follow, the camp deteriorates into a slum area, ripe with violence, drug-abuse and inter-species prostitution. Because of their crustacean-like appearance, the aliens are derogatorily called ‘prawns,’ and all humans in Johannesburg seem to agree that “the prawns must go.” In 2010, the South African government decides on a relocation scheme and contracts Multi-National United (MNU), a private company mainly interested in alien weaponry, to transfer the aliens into a new camp at a safe 200 kilometers’ distance from the city. Wikus van de Merwe (Sharlto Copley), a simple Afrikaner clerk at MNU, is to lead this operation, assisted by a brutal armed force, but he fails; while handing out eviction notices to the inhabitants of District 9, he accidentally touches a spray with alien DNA, mutates into an alien, is hunted by his own government, finds refuge in District 9, and learns to sympathize with the outcasts whom he finally helps to escape in their spaceship.

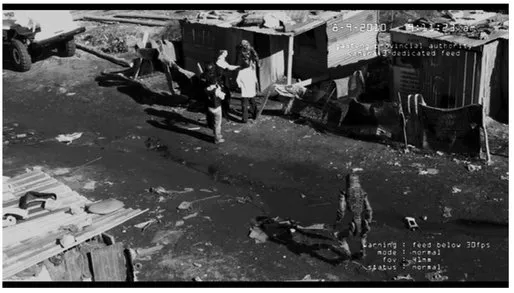

This is the story of District 9, an alien movie directed by the South African filmmaker Neill Blomkamp and produced by Peter Jackson. It came out in 2009, to great international acclaim. The movie starts as a mock-documentary, combining fictional interviews, television news footage, and videos from surveillance cameras (see Figure 4). This fictive footage, all edited at a rapid pace, reconstructs from the vantage point of a near future the fictional history of aliens in Johannesburg since 1982 and provides ‘evidence’ of Wikus van de Merwe’s actions and whereabouts up to the point at which he disappears off the radars of MNU and the South African government into District 9. Halfway through the movie, the mock-documentary mode changes into a conventional cinematic narrative. Wikus’ unrecorded further fate, his transformation into an alien, is represented much in the style of alien movies from the 1980s.

Fig. 1. The alien spaceship over Johannesburg; screenshot, District 9 (dir. N. Blomkamp, 2009).

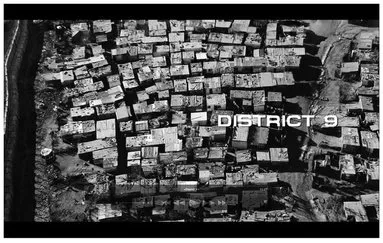

Fig. 2. District 9 (shot on location in Chiawelo, Johannesburg); screenshot, District 9 (dir. N. Blomkamp, 2009).

District 9, the alien movie set in Johannesburg, does something that seems worth drawing attention to in a collection on transnational memory, which has to do with the obvious reference, in the movie’s title, to Cape Town’s District Six. With its focus on a government scheme that aims at moving aliens dwelling in an inner-city slum area to an internment camp outside the city, the movie clearly refers to the history of apartheid and the ways in which it was acted out in South African cities. In enormous relocation schemes, the country’s less-privileged people, mostly ‘black’ and ‘colored,’ were forcibly moved from inner city compounds to townships at the fringes of the cities.

In a science fiction setting and an allegorical framework, the movie re-enacts the violent history of apartheid, which, although it belongs to the past now, has permanently shaped the face of South African cities. It does so by substituting a present-day story about speciesism for South Africa’s history of racism: humans of all races fight against the aliens. While in postcolonial studies, there has been work on how alien movies, from Alien Nation (1988) to Independence Day (1996), address, articulate, and reframe ideas and anxieties about race (see, for example, Sardar and Cubitt 2002) and it would certainly be interesting to study how this tried and tested allegorical pattern is transformed in District 9 – which leaves the spectator feeling utterly alienated by the violence and mercilessness of the human beings – the main aim of this chapter is to address a somewhat different question. If a contemporary alien movie is set in Johannesburg, if it half-mockingly, half-critically refers to segregation as it was practiced in South Africa, if it shows the inhumanity of an apartheid-legislation that enables forced removals, if, in fact, the movie is shot on location in a part of Soweto, the squatter camp of Chiawelo – why is such a movie not called ‘Aliens in Soweto,’ or, for that matter, ‘Aliens in Sophiatown,’ thus referring to the inner-city districts and townships that actually belong to the city of Johannesburg and its apartheid-history? Why ‘District 9’?

It seems that, rather than Sophiatown or Soweto, it is Cape Town’s District Six, which has, over the past two decades or so, been turned into a powerful transnationally available schema to draw on when it comes to giving form to issues of racism, segregation, victimization, and the forced removal of people from their original place.

According to cognitive psychology, schemata are patterns and structures of knowledge on the basis of which we make assumptions regarding specific objects, people, situations and the relation between them. Schemata reduce real-world complexity and guide perception and remembering. As Frederic Bartlett already showed in his Remembering, schemata are always culture-specific (Bartlett 1932) and emerge from socially shared knowledge systems. In our age of global media cultures and transnational migration, the circles, or social frameworks (Halbwachs 1925), of this sharing are ever expanding. With migrants and mass media as their carriers, cultural schemata are set to ‘travel’ and may thus acquire transnational and transcultural dimensions (see Erll 2011b). They appear and are used in different local contexts across the world. In the form of travelling schemata, patterns of knowledge cut across boundaries of language, cultural communities, or nations.

Fig. 3. Apartheid between humans and aliens; screenshot, District 9 (dir. N. Blomkamp, 2009).

In order to describe the transnational dynamics of remembering connected with ‘District Six,’ I will, in the following, distinguish between two categories of schemata: visual schemata (icons), which are the result of iconization, and story-schemata (narratives), which are the result of topicalization and narrativization. The focus will be on the medial – more precisely: plurimedial – production of key icons and narratives about District Six. The goal is to understand how the ‘District Six’-schema has been set to travel: from Cape Town to Johannesburg, from South Africa to worldwide cinemas, from the serious, and violent, history of apartheid to the half-mocking imagination of an alternative alien present.

Fig. 4. Forced removals viewed form surveillance cameras; screenshot, District 9 (dir. N. Blomkamp, 2009).

District Six and the history of South African apartheid

When the apartheid regime came into power in South Africa in 1948, an array of new laws was introduced. The Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act of 1949 put a ban on marriages between white people and people of other races. The Immorality Amendment Act of 1950 prohibited extra-marital sexual relationships between white and black people. The Population Registration Act of 1950 meant that every person’s race was classified and recorded in a national register. This register knew the categories of four racial groups: ‘native,’ ‘white,’ ‘colored,’ and ‘Asian.’ The Group Areas Act of 1950 put all these forms of segregation into spatial practice. It created apartheid within the city itself, segregating people of different ‘races’ into different urban spaces.

The aim of the Group Areas Act was to exclude non-whites from living in the most developed and attractive urban areas. They were forcibly removed from their neighborhoods and dumped in townships which were often far away from the city centers. Cape Town’s District Six was declared a ‘white area’ under the Group areas Act in 1966. In 1968, the forced removals started. The district’s inhabitants were relocated in the Cape Flats township complex, in an until then uninhabited flat and sandy area more than twenty kilometers south-east of Cape Town often called ‘the dumping ground of apartheid.’ The forced removals stretched over a period of more than fifteen years. In the end, with the exception of some places of worship, all of the old houses were bulldozed. Even today, District Six is an empty space within the city. Ironically, the district was never ‘redeveloped’ into a white area. In the 1980s, the Hands Off District Six Campaign was formed and exerted strong pressure on the government. In 1994, with the end of apartheid, the National Congress recognized the claims of former residents and started to organize their return, which, however, is still in process.

The specificity of District Six is that it was a multi-ethnic quarter with a long history. Already in the late nineteenth century it was a mixed community of former slaves, immigrants, merchants and artisans. Many so-called ‘Cape Malays,’ descendants of people who were brought from Malaysia to South Africa by the Dutch East India Company in the seventeenth century, had settled in the area. Next to them lived Xhosa people, Indians, and, in less large groups, Afrikaners, white people of British descent, and Jews. District Six, in short, featured almost all of the ethnic communities living in that part of South Africa at that time.

In the 1960s, according to the South African government, District Six had deteriorated into a slum area which had to be cleared. The government portrayed the district as a dangerous place, full of crime, gambling, drinking, and prostitution. This may have been true (the stories by Alex La Guma, for example, suggest that District Six was certainly not a convent), but for the government – with its obsession with racial purity and segregation – the ‘mixedness’ of District Six seems to have been the greatest outrage. Furthermore, the area’s location near the city centre, Table Mountain, and the harbor meant that District Six could be turned into a valuable residential area for rich white people.

Mediations of ‘District Six’

How, then, did District Six turn from such a specific historical place into a travelling schema? The clue is mediation. This can already be sensed in the prime site of District Six remembrance, the District Six Museum, which was founded in 1994 and is located in the District’s Central Methodist Church in Buitenkant Street, a former “sanctuary for political opponents and victims of apartheid” (Coombes 2003, 126). Using the terms introduced by Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin in their theory of remediation (1999), the District Six Museum can be said to bring back the disappeared quarter by means of hypermediation. Dating from its inaugural exhibition in 1994, Streets: Retracing District Six, its ground floor is covered with the painting of a large street map of District Six. There are columns of original street signs from the old district and large-scale photographic portraits of well-known former residents. The museum collection features more than 8,500 photographs of District Six and its families. It provides audio-visual material and oral history recordings. In 2000, the exhibition Digging Deeper created soundscapes out of the voices of ex-residents. Some of these various media of cultural memory are also available online on the museum’s webpage, including a virtual walk through the district.

Arguably, the museum has become such a powerful site of memory because it connects these manifold mediations with various forms of social performance. This social embeddedness can be traced back to the museum’s origins in the Hands Off District Six Campaign, and is still testified to today in the museum’s self-description as a “a living memorial” with an archive that is “a living organism,” and by its strong reliance on visitors’ and ex-residents’ active participation as well as its emphasis on being a “community museum.” According to the historian Ciraj Rassool, one of the museum’s trustees and most prolific scholars, the District Six Museum can thus be described as “a hybrid space,” which combines “scholarship, research, collection and museum aesthetics with community forms of governance and accountability, and land claim politics of representation and restitution” (Rassool 2006, 15). By offering a rich texture of medial representations, material traces of the past, and their various social uses, the museum (hyper-)mediates the district’s history and seems to recreate the real to the extent that “soon after its creation, many visitors began to refer to the museum simply as ‘District Six’.” The site of the district’s memorialization and commemoration “had to perform the work of satisfying the desire for the real” (Rassool 2006, 13).

But also beyond this particular museum, there is a long history of District Six mediations. In painting, for example, artists such as John Dronsfield, Gregoire Boonzaier, Gerard Sekoto and Kenneth Baker, have captured versions of life in the district. Professional photographers, such as Cloete Breytenbach, Jillian Edelstein, Paul Grendon, Jan Greshoff, George Hallett, Jackie Heyns, Jimi Matthews, and Jansje Wissema, have substantially shaped the imagination of District Six. Various forms of entertainment also play a key role in the memory of District Six: Hybrid Cape Jazz, for example, can be understood as a medial self-expression of the district’s creole realities. A District Six musical was produced by David Kramer and Taliep Petersen in 1986. Short films about District Six, such as Lindy Wilson’s documentary Last Supper at Horstley Street (1983) and Yunus Ahmed’s Dear Grandfather, Your Right Foot is Missing (1984) represent the time during and after the forced removals and their impact on resident families.

Literature has had its share in the representation of District Six memories, too; poetry on the topic was written by James Matthews, Adam Small, Dollar Brand (Abdullah Ibrahim), and Cosmo Pieterse. Peter Abraham’s Path of Thunder (1948) is arguably (Rive 1990, 113) the earliest published novel about District Six. The most famous works, ho...