With the recent development of new technological devices such as smartphones and tablets, and with the rise of Web 2.0 technologies, for retailers the Internet has become much more than a facilitating tool for information gathering and communication (PWC, 2013). In fact, an increasing number of consumers take advantage of these new technological devices, shopping at any time they wish and effortlessly switching between online and offline channels. Thus, consumers use online channels (e.g., online shops or in-store terminals) as well as traditional channels (e.g., bricks-and-mortar stores or catalogues) interchangeably, and along all phases of the buying process (search, purchasing, and post-purchasing phases). Research on multi-channel marketing refers to such consumer behavior as cross-channel shopping (e.g., Verhoef, Neslin and Vroomen, 2007; Chatterjee, 2010). Results from two empirical studies emphasize this change in consumer behavior by showing that, currently, 20 percent of German and Swiss shoppers are already cross-channel shoppers, preferring to switch between online and offline shopping channels (Rudolph et al., 2013).

1.1 The Rise of Cross-Channel Shopping

The following story of “Mike” demonstrates how new technological devices are revolutionizing customers’ shopping behavior. Mike, 28, works as a project manager in the pharmaceutical industry. In addition to his laptop, he also possesses one personal smartphone, one business smartphone, and a tablet PC. On Thursday night after a long business day, he is watching television and notices a commercial for a well-known outdoor sporting goods brand. This advertisement reminds him that he is in dire need of new hiking boots for a two-day hiking trip with his girlfriend. Still on his couch, he takes his tablet PC, browses through the advertised websites to find which retailer in his area has the specific brand available. He sees that the outdoor sporting goods retailer Outdoor Guy has the brand in stock and offers a function on its webpage that allows him to arrange for a personal shopping appointment. Thus, with only two clicks, he makes a reservation for in-store assistance the following day at 11 a.m., when he has free time between two business meetings. Through the website, he selects five different pairs of boots he wants to try on during his store visit. When he enters the local branch of the sporting goods store, the sales representative already waits with the reserved boots, and also shows him two additional models in the collection that had just arrived. After a few minutes, Mike considers a nice pair of boots that seems to match his needs. However, it is a brand that he has never heard of and he is not sure whether to entirely trust the salesperson. He grabs his smartphone and uses the retailer’s barcode scan function to find a wealth of online information, videos, and customer reviews. Even though the online information corresponds with the information provided by the store sales representative, he still thinks he might get a better deal if he buys the boots online, so does not make a purchase. That evening he browses through a price comparison site and the retailer’s website, where he is offered assistance from a customer service representative. He selects the “Call me now” button and receives a VoIP-call from the retailer’s call-center agent. After an informative call, Mike is finally convinced that he has found the perfect boots and orders them online from the outdoor retailers’ online shop. He is particularly pleased to note that the retailer offers free delivery, guaranteed within the next forty-eight hours, just in time for his hiking event.

Unfortunately, Mike’s hiking trip turns out to be a nightmare – an hour into the steep climb he gets blisters because the shoes are too tight at the heel. On Sunday evening after the hiking trip, he calls the online-store support team to ask for advice. The call-center agent proposes another personal shopping visit to a store location that has what the retailer calls a foot-scan service. The call-center agent arranges a store appointment in the city where Mike is traveling for a business trip on Monday morning. Because he does not want to carry the unsatisfactory boots with him on his business trip, he decides to take advantage of the free shipping service and sends the boots back by mail – getting the full refund on his loyalty card account. On Monday, Mike is pleased when, as soon as he walks into the store, the sales representative knows who he is and that he needs assistance to select boots with a better fit. Using the newly installed three-dimensional foot-scan application on the sales clerk’s tablet PC, Mike can choose between three different pairs of boots tailored to his needs. He selects a pair and, as compensation for the inconvenience caused by the ill-fitting shoe, receives an email with a ten-percent discount coupon on all apparel items, redeemable immediately through any of the retailer’s sales channels. Because Mike cannot carry the boots with him to his next business meeting, he chooses to have them shipped home free of charge, along with a fleece jacket that he bought with his coupon.

A New Customer Group

In the preceding vignette, Mike’s shopping behavior is not unusual, as it illustrates the current move toward cross-channel shopping behavior. The advent of the new shopping phenomenon has major implications for all retailers – multi-channel players, classic bricks-and-mortar players, and pure online players. On the one hand, based on evidence of channel-switching behavior, consumers seem to be less loyal to specific retailers, switching channels and retailers during the shopping process (Chiu et al., 2011). On the other hand, channel-switching consumers such as Mike are a particularly valuable and lucrative customer group. They spend more, on average, increasing their value over single-channel customers (Kushwaha and Shankar, 2008a; Neslin et al., 2006). Multi-channel retailers targeting this new customer group can achieve increased revenues if they are able to keep cross-channel customers loyal by offering channel-switching opportunities during the shopping process.

Our latest consumer survey based on close to 2,800 interviews in Austria, Germany and Switzerland proofs an increasing interest in the so-called cross-channel shopping. The following research findings urge managers from different industries to get a better understanding of consumer behavior in the digital world (Rudolph et al., 2014):

- More than half of consumers know companies that sell products online and offline. The awareness of cross-channel retailers is rising.

- More and more shoppers use different distribution channels when shopping for consumer electronics, furniture, textiles, cosmetics, shoes or even grocery. In 2014 26.5 percent visited the retailer’s online-shop and the bricks-and-mortar store in their path to purchase.

- On average among all categories 28.9 percent of consumers visited the retailer’s online shop before purchasing the product in the retailer’s bricks-and-mortar store. Research online and purchase offline, the so called ROPO-Effect, is becoming more popular.

- In terms of touch points usage when shopping online shops are getting more important. 63.3 percent of cross-channel shoppers visit the retailer’s online-shop in the purchasing process; 62.6 percent visit the retailers’ bricks-and-mortar store (N = 2,780). Allthough the online-shop is visited more frequently in the purchasing process, the retailer’s bricks-and-mortar store is still evaluated slightly more important for the purchasing decision.

Off course, our findings differ between retailing categories a lot. In consumer electronics, for example, the consumer decision journey compared to grocery purchases is much longer, consists of much more touch points and is more price driven. Therefore, each company should spend more attention to understand the consumer decision journey of their target groups. This journey was different 5 years ago and will be extended through cross-channel possibilities and more intense smartphone usage.

In order to compete with pure online players that contest their market shares, multi-channel retailers are highly challenged to harmonize their online and offline channels. If they manage to offer smooth shopping experiences and seamless switching opportunities across all online and offline channels of an integrated channel system, retailers will not only retain customer loyalty, but will also attract new cross-channel shoppers from other players (Zhang et al., 2010). However, despite the considerable potential inherent in the cross-channel shopper phenomenon, many multi-channel retailers struggle to successfully cater to this change in customer behavior. Although almost all bricks-and-mortar retailers think that cross-channel management is a key for future success, only 46 percent have already defined a cross-channel strategy (BearingPoint, 2012). Even though the change in consumer behavior toward cross-channel shopping can be viewed as the most disruptive change in the retail environment since the advent of the discount phenomenon in the late 1960’s, many multi-channel incumbents have embarked on the pursuit of cross-channel management to actively defend their market shares against pure online players (PWC, 2013).

1.2 The Era of Cross-Channel Management

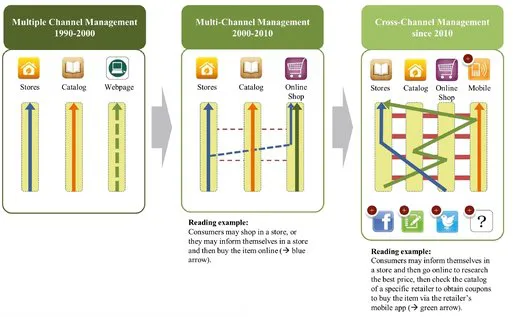

Research in channel retailing has evolved significantly in the last two decades moving from multiple channel management, to multi-channel management, to cross-channel management. Until 2000, multiple channel management simply referred to managing more than one distribution channel pipeline (Frazier, 1999). From the beginning of the digital age, around 1990, until 2010, multi-channel management indicated “a set of activities involved in selling merchandise or services to consumers through more than one channel” (Levy & Weitz, 2009). Since 2010, pure online retailers have steeply increased their market share (e.g., Amazon) and classic retailers have started to intertwine their online and offline channels (e.g., Apple) based on new technological devices that enable and inspire shoppers to switch between online and offline channels. A new era of channel management called cross-channel management was born. Compared to multi-channel management, cross-channel management goes one step further and can be described as management that deliberately focuses on the integration of all online and offline channels in order to offer customers seamless switching opportunities across all channels (Zhang et al., 2010). Figure 1.1 illustrates the three eras of channel retailing.

Fig. 1.1. The Three Eras of Channel Management.

On their journey toward channel integration, multi-channel retailers need to decide how to orchestrate their various consumer touch points. Thus, they must deal with the question of how to intertwine their online and offline distribution channels (e.g., stores, call center, webshop, mobile-device shop, or even Facebook) to be able to offer compelling switching opportunities to consumers (Zhang et al., 2010). However, they also need to think about how they can interlink classic, online, and social media communication channels (i.e., classic: events, flyers, television commercials; online: newsletters, coupons; social: tags, blogs, recommendations) to address and promote consumers’ channel-switching behavior – for example, when customers use one distribution channel for research and another for purchasing (Fram...