- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Biohydrogen

About this book

Biohydrogen is considered the most promising energy carrier and its utilization for energy storage is a timely technology. This book presents latest research results and strategies evolving from an international research cooperation, discussing the current status of Biohydrogen research and picturing future trends and applications.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Cyanobacterial design cell for the production of hydrogen from water

1.1 Introduction: Why hydrogen producing cells?

Due to energetic considerations, microalgae are becoming more and more popular for the production of biomass in general and the production of high value products in special applications. Major benefits of these organisms are the use of sunlight as a free energy source and the fixation of CO2 by incorporation into reduced carbon compounds. Both can contribute to reducing atmospheric CO2 (a “climate killer” gas) and also can be regarded as energy-rich storage compounds for periods of energy shortage. There are, however, also alternative strategies for converting sun energy directly into biofuels, i.e. high energy compounds, which are energetically and economically highly attractive: The classical route of energy storage via carbon compounds is extremely inefficient, ranging in most cases (due to metabolic constrains) from below 1 % and only in exceptional cases up to about 5 % efficiency, which is in contrast to the high efficiency of the primary (light-) reactions of photosynthesis [2], [3]. For this reason, biofuel production has to be coupled as closely as possible to the light reactions of photosynthesis, combined with a re-routing of electrons which minimizes the steps of biofuel production and also the loss of electrons due to carbon fixation [4] [5] [6]. The attractive overall strategy is to receive the required electrons from the most abundant and cheapest compound available on earth – water – and to transfer them directly to the biofuel. The most useful and most direct-to-produce biofuel would be hydrogen [6], as it is a high energy compound that releases its energy by reaction with oxygen, producing as the only “waste” product again the starting compound water. The energy of this reaction can be used directly – for instance in a fuel cell – or can be easily stored for a longer time. By transferring the electrons primarily to protons instead of reducing CO2, this process is completely environmentally acceptable. In contrast, the release of energy stored in reduced carbon compounds inevitably leads to the production of CO2 – besides the high energy loss due to the many metabolic steps involved.

As this is a new concept which is against the principles of nature – it does not secure survival of the cell by storing energy but rather “wastes” the collected sun energy by setting free the high energy compound hydrogen – the metabolism of such a cell has to be modified in many individual steps. This is also a challenge from the bioenergetic point of view, since the amount of sun energy collected by a photosynthetic cell that can be harnessed for mankind is completely unknown. Such an “exploitation”

Dedicated to Prof. Dr. K.-E. Jäger on the occasion of his 60th birthday

of cells has already been established for many biotechnological applications up to industrial scale in “white” biotechnology; it is, however, very new for “green” or “blue” biotechnology and requires new techniques of “synthetic biology” currently being developed for microalgae with very special requirements (see Chapter 8) [8] [9]. In the end, microalgal cells should be “designed” for maximal hydrogen production in specially designed photobioreactors which enable the efficient use of sun energy and the optimal harvest of hydrogen by gas separation.

Although such optimized cells – due to obvious reasons – cannot be found in nature, extremely efficient natural catalysts have been developed in the course of evolution which can synthesize hydrogen by reducing protons [10] or make use of hydrogen as an energy source in the reverse direction: The hydrogenases (H2ase) [11]. While these enzymes were essential in the early stage of evolution under anoxigenic conditions, when hydrogen could be used as energy source, such an application is today restricted to very special environmental conditions. For this reason, these enzymes exist only in small amounts and only in organisms which (partly) have to survive under anaerobic conditions – some bacteria, cyanobacteria and green algae (for details see Chapters 3, 4, 5 and 7). Since the basis of our design cell organism should be water-splitting photosynthesis, only two groups of organisms provide reasonable starting materials including pre-existing H2ases [12]: cyanobacteria or green algae. Both groups have still preserved some routes for light dependent H2 production which are illustrated in Figure 1.1

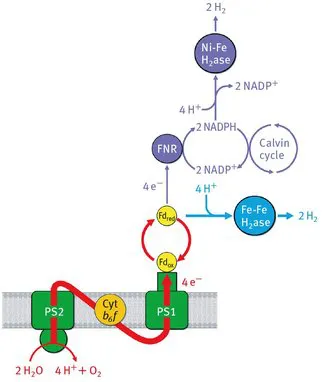

Cyanobacteria contain exclusively [NiFe]-type H2ases which are coupled to photosynthetic electron transport via NADPH [13], which in turn is produced by Ferredoxin-NADP +-Oxidoreductase (FNR), or may even be coupled directly to Ferredoxin (Fd) [14] (for details see Chapter 10). Between Photosystem 1 (PS1) and this H2ase several electron transfer steps are involved including many competitive reactions –especially involving Ferredoxin (Fd) and NADPH – which “dilute” the amount of electrons finally available for hydrogen production. In contrast, green algae contain [FeFe]-type H2ases which are most directly coupled to PS1 via Fd and also show much higher activities than [NiFe]-H2ases (for details see Chapters 3, 5 and 7).

Since cyanobacteria are much easier to genetically engineer than green algae and also are the most simple organized cells with the ability for water-splitting photosynthesis, a cyanobacterial model organism such as the well-characterized Synechocystis PCC 6803 [15] is the ideal chassis for the development of a “design cell”. An Fd-coupled high-turnover-H2ase (such as the [FeFe]-H2ase of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii –see Chapter 3) has to be integrated into this chassis – including the complete maturation machinery. In order to achieve this goal, many obstacles have to be overcome and many parameters have to be adapted or optimized.

This chapter provides information on the strategy and the realization of this long-term project; it also helps to indicate the potential and the possible limitations of this approach by some examples of practical cellular design.

Figure 1.1: Photosynthetic electron transport from water splitting at PS2 (source) to H2ase in cyanobacteria (purple, sink = [NiFe]-type H2ase) and in green algae (blue, sink = [FeFe]-type H2ase). In the case of the [FeFe]-H2ase, hydrogen production is completely uncoupled from the CO2 fixation pathway (Calvin cycle) due to an early branching off of photosynthetic electrons at Ferredoxin (Fd).

1.2 Antenna size reduction

Future hydrogen production by the design cell depends especially on the electron transport rate between water-splitting Photosystem 2 (PS2) and “integrated” hydrogenase, which is hampered by an imbalanced amount of PS2 to PS1 in Synechocystis wildtype (WT) cells. As this PS2/PS1 ratio is approximately 1/10 (F. Mamedov, personal communication) the low content of PS2 is...

Table of contents

- Also of interest

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of contributing authors

- Preface

- 1 Cyanobacterial design cell for the production of hydrogen from water

- 2 Analysis and assessment of current photobioreactor systems for photobiological hydrogen production

- 3 Catalytic properties and maturation of [FeFe]-hydrogenases

- 4 Oxygen-tolerant hydrogenases and their biotechnological potential

- 5 Metal centers in hydrogenase enzymes studied by X-ray spectroscopy

- 6 Structure and function of [Fe]-hydrogenase and biosynthesis of the FeGP cofactor

- 7 Hydrogenase evolution and function in eukaryotic algae

- 8 Engineering of cyanobacteria for increased hydrogen production

- 9 Semi-artificial photosynthetic Z-scheme for hydrogen production from water

- 10 Photosynthesis and hydrogen metabolism revisited. On the potential of light-driven hydrogen production in vitro

- 11 Re-routing redox chains for directed photocatalysis

- 12 Energy and entropy engineering on sunlight conversion to hydrogen using photosynthetic bacteria

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Biohydrogen by Matthias Rögner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biochemistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.