- 164 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Industrial Chemistry

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Industrial Chemistry by Mark Anthony Benvenuto in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Chemistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Overview and introduction to the chemical industry

1.1 Focus and depth

Over 70,000 chemicals are produced annually on a large scale and are either used in some further chemical transformation, or are incorporated into an end product. Perhaps obviously, nothing short of an exhaustive encyclopedia could discuss all of them, or even list all their uses. Some focus is required in order to cover a selected series of topics within this extensive, broad field.

Similarly, it would be difficult to produce a volume that simply lists a series of chapters corresponding to the largest commodity chemicals used in the world today which were left out of Industrial Chemistry, because such a “laundry list” does little to place any of these chemicals and materials in a larger context. This book will attempt to discuss the large process chemistry omitted in the initial volume and will also build greater context among the processes. Thus, while there are chapters on chemicals that are certainly organic – those that are only produced from the refining of crude oil –as well as on those that are distinctly inorganic, there are also several chapters that straddle borders, such as hydrogen peroxide, food additives, bromine, fluorine, and asphalt.

Most developed nations track self-determined lists of materials that are deemed vital to their economies and defense. For example, in the United States, the Department of Energy maintains a Critical Materials Strategy (Department of Energy , 2014), the Department of Defense has published a Strategic and Critical Materials 2013 Report on Stockpile Requirements (Department of Defense, 2014), and the United States Geological Survey produces a Mineral Commodities Summary each year (United States Geological Survey, 2014). These reports indicate the quantities of various chemicals that are produced annually and how much the United States imports from other nations. Similar documents are produced by the ministries of defense, education, and economic growth in most European and Pacific nations. In addition to these, several national and internationally learned societies keep track of chemical and material production, and usually publish their own lists and compilations of statistics regarding them (Chemical and Engineering News, 2014; Royal Society of Chemistry, 2014; European Chemical Industry Council, 2014; Society of Chemical Manufacturers and Affiliates, 2014; Gesellschaft Deutscher Chemiker, 2014; Chemical Society of Japan, 2014; Royal Australian Chemical Institute, 2014; International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, 2014). Also, trans-national organizations like the United Nations and the Arctic Economic Council monitor chemical production and industrial use in their annual reports and in more targeted documents (United Nations Environment Programme, 2012; United Nations Environmental Programme, 2014; Arctic Council, 2014).

The chemicals and materials in these chapters are not always produced on a large enough scale that they make it on to any “top 100” list of the above-mentioned organizations. But each material is vitally important in some way, and thus is worthy of discussion. Therefore, we have tried to include many of them in this book.

1.2 Recycling

There is no doubt that the chemical industry today has been greatly transformed from the industry of the 1960s. It has been noted that from 1945 to perhaps 1965, the generation that had fought the single largest war humanity had ever seen returned home and built a society and a quality of life that had also never been seen before. The infrastructure in the countries that had been embroiled in that war expanded greatly, which meant the use of millions of tons of refined metals, concrete, asphalt, glass, and petroleum products – the latter was in part for the fuels for the vehicles that made this all happen. Highways were constructed, cities built or rebuilt and water and energy infrastructures were put in place or replaced. All of this required massive amounts of chemicals and all of it generated waste.

The developed world has changed since that time. Now there is recognition that this level of man-made change has affected the world itself. While debate continues over resource depletion, climate change, the first priority use of arable land and the pollution of fresh and salt waters, the chemical industry has adapted and has moved toward cleaner, more environmentally benign practices for many of the production streams that manufacture and refine the chemicals we use today.

A part of each chapter in this book has been devoted to the concept of recycling and reuse of the material upon which it focuses. When no recycling or reuse is possible, this is acknowledged. But when some process has been improved, made safer, or made economically more sound through the practices of good stewardship on the part of producers, including recycling or reuse, that too is also acknowledged.

Bibliography

Arctic Council. Website. (Accessed 7 June 2014, as: http://www.arctic-council.org/index.php/en/arctic-economic-council).

Chemical & Engineering News. Website. (Accessed 5 June 2014, as: http://cen.acs.org/index.html).

Chemical Society of Japan. Website. (Accessed 5 June 2014, as: https://www.csj.jp/index-e.html).

Department of Defense. Strategic and Critical Materials 2013 Report on Stockpile Requirements. Website. (Accessed 7 June 2014, as: http://mineralsmakelife.org/assets/images/content/resources/Strategic_and_Critical_Materials_2013_Report_on_Stockpile_Requirements.pdf).

Department of Energy. Critical Materials Strategy. Website. (Accessed 7 June 2014, as: http:/energy.gov/sites/prod/files/DOE_CMS2011_FINAL_Full.pdf).

European Chemical Industry Council. Website. (Accessed 20 May, 2014, as: http://www.cefic.org).

Gesellschaft Deutscher Chemiker. Website. (Accessed 5 June 2014, as: https://www.gdch.de/home.html).

International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, IUPAC. Website. (Accessed 5 June 2014, as: http://www.iupac.org/).

Royal Australian Chemical Institute, RACI. Website. (Accessed 5 June 2014, as: http://www.raci.org.au/).

Royal Society of Chemistry. Website. (Accessed 5 June 2014, as: http://www.rsc.org).

Society of Chemical Manufacturers and Affiliates. Website. (Accessed 5 June 2014, as: http://www.socma.com/).

United Nations Environment Programme 2012 Annual Report. Website. (Accessed 7 June 2014, as: http://www.unep.org/gc/gc27/docs/UNEP_ANNUAL_REPORT_2012.pdf).

United Nations Environmental Programme “Costs of Inaction on the Sound Management of Chemicals,” Website. (Accessed 7 June 2014, as: http://www.unep.org/chemicalsandwaste/Portals/9/Mainstreaming/CostOfInaction/Report_Cost_of_Inaction_Feb2013.pdf).

United States Geological Survey. Mineral Commodities Summary 2013. Website. (Accessed 7 June 2014, as: http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/mcs/2013/mcs2013.pdf).

2 Phosgene (carbonyl dichloride)

Throughout history, certain chemicals or materials have gained fame or notoriety for a wide variety of reasons. Gold has been valued in almost all civilizations from ancient times to the present for no reason except its visual beauty. Iron has been valued because of its ability to hold an edge, which makes it useful in forming tools and weapons. Arsenic and arsenic compounds have been known to be poisons in several cultures – and indeed, have been considered a weapon within an assassin’s arsenal for hundreds of years. More recently, both phosgene and one of its starting materials, chlorine, have been considered one of the worst of battlefield weapons, namely, poison gas.

Elemental chlorine gas was indeed the first chemical warfare agent widely used on the western front of the First World War. Although the gas is poisonous, at the concentrations that were delivered by artillery in that war, it was seldom lethal by itself. It is denser than air, thus seeping and pouring into the trenches, forcing soldiers without gas helmets to rise up for air, where enemy soldiers could then shoot at them. Phosgene, used later in the war, was far more lethal. When inhaled even in small amounts, HCl forms in the lungs, affecting what is called “dry land drowning” as lung tissue was destroyed. The limited number of survivors of phosgene attacks claim that small doses of it smell like newly mown hay, or fresh-cut wheat.

It is staggeringly ironic than that elemental chlorine is today used as an inexpensive antibacterial in water, and thus has saved countless people from a wide variety of diseases. Even more so that phosgene is used as a starting material for several very useful plastics, all of which are produced in large volumes.

2.1 Method of production

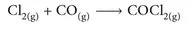

The reaction chemistry that illustrates the synthesis of phosgene is a deceptively simple addition reaction. It can be represented as

This does not however give any details about the reaction conditions, which are important for optimal yield of phosgene. The two reactants are passed through activated carbon, sometimes called activated charcoal. This serves a catalytic role. Since the reaction is exothermic and usually runs at a temperature zone of 50–150 °C, the reactor is typically cooled during the process.

The chlorine reactant is produced as one of the three products in what is called the chlor-alkali process. The other products of this process are sodium hydroxide and hydrogen gas. Carbon monoxide is usually produced by the reaction of carbon dioxide and carbon at elevated temperatures.

2.2 Volume of production annually

It is difficult to put a number on phosgene production annually, because the chemical’s toxicity dictates that it is immediately used for ...

Table of contents

- Also of Interest

- Title Page

- Author

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Table of Contents

- 1 Overview and introduction to the chemical industry

- 2 Phosgene (carbonyl dichloride)

- 3 Butyraldehyde

- 4 Acetic anhydride

- 5 Linear alpha olefins LAO)

- 6 n-Butanol (1-butanol or n-butyl alcohol)

- 7 Methyl methacrylate

- 8 Hexamethylene diamine HMDA)

- 9 Hydrogen cyanide (HCN)

- 10 Bisphenol A

- 11 Food additives

- 12 Vitamins

- 13 Hydrogen peroxide

- 14 Lithium

- 15 Tungsten

- 16 Sodium

- 17 Lead

- 18 Rare earth elements

- 19 Thorium

- 20 Catalysts

- 21 Bromine

- 22 Fluorine

- 23 Glass

- 24 Cement

- 25 Asphalt

- 26 Biofuels and bioplastics

- Index