eBook - ePub

Too Big to Fail III: Structural Reform Proposals

Should We Break Up the Banks?

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Too Big to Fail III: Structural Reform Proposals

Should We Break Up the Banks?

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Too Big to Fail III: Structural Reform Proposals by Andreas Dombret, Patrick S. Kenadjian, Andreas Dombret,Patrick S. Kenadjian in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Droit & Droit des faillites et de l'insolvabilité. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Structural Separation and Bank Resolution

1. Why Structural Separation?

The recollection in tranquillity of events of great stress usually discloses ideas which, passionately believed at the time, now appear fantastical. The first world war urban legend of Russian soldiers marching through the English countryside “with snow on their boots” was passionately believed despite its utter implausibility. A similar process of thought during the financial crisis seems to have led to an outbreak of faith in “narrow banking”; a manifestation of the belief that if only modern banks could be wished away, we could return to the comforting certainties of the fictional bankers of “Dad’s Army” and “Its a Wonderful Life”

This approach – of wishing away the world as it is in favour of a mythological past – is as old as recorded civilisation. However it had a curious offshoot in the form of regulatory proposals to separate out “Captain Mainwaring-style” banking from the frightening business of derivatives, securitisations et. al. which were confidently believed by the uninformed to have “caused the crisis”.

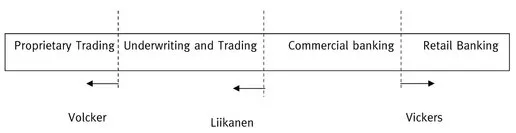

Complicating matters further is the fact that such structural separation proposals came in a variety of different flavours. In addition to “Volcker” type proposals, which prohibit bank groups from engaging in certain activities, Europe has managed to generate two different sets of proposals for separating activities within bank groups. One of these is the UK “Vickers” proposal, which is aimed at ring-fencing retail deposit taking into a separate legal entity; the other is the EU “Liikanen” proposal, which is aimed at separating market trading activity into a separate legal entity. These differing policies can best be explained graphically as follows:

The point which this illustrates is that to impose all of these simultaneously on a single entity would, in effect, involve dividing it into four, with the Volcker part being squeezed into a separate corporate group and the remaining three components coexisting under a common holding company. No policymaker currently considers that imposing all of these restrictions on a single entity would be a good idea (although this may be the ultimate fate of UK deposit-taking banks). However, it does illustrate the fact that to talk about structural separation as if it were a single concept is to misunderstand the nature of the problem.

This proliferation of structural separation proposals needs to be systematised before the impact of structural separation on resolution can be considered. Ordinarily, this could be done by reference to the policy aims which the separation is intended to secure. However, identifying these aims is curiously difficult –the documents which propose ring-fencing tend to proceed by assuming its benefits rather than setting out a case for them.

Vickers-style separation

In this regard, the observations of Sir John Vickers, the chair of the UK Independent Banking Commission report (the “Vickers Comission”) are particularly enlightening

“… the Commission sees merit in a UK retail ‘ring-fence’. This would require universal banks to maintain the UK retail capital ratio – that is, not to run down the capital supporting UK retail activities below the required level in order to shift it, say, to global wholesale and investment banking. Our current view is that such a limit on banks’ freedom to deplete capital would be proportionate and in the public interest, and would preserve benefits of universal banking while reducing risks. Without it, capital requirements higher than 10 % across the board might well be called for”.133

Leaving aside the fact that capital requirements of 10 % are now a distant memory – requirements for global banks are much higher – the underlying idea held by the commission of how a bank works, with capital being “shifted” within a single legal entity from one part to another, is particularly disturbing, in terms of highlighting the grasp of those writing the report of the topic concerned. A slightly better effort was made by HM Treasury, whose paper on the implementation of the Vickers ring-fence summed up its objectives as being:-

- – to insulate critical banking services from shocks elsewhere in the financial system; and

- – to make it easier to preserve the continuity of those services, while resolving financial institutions in an orderly manner and without injecting taxpayer funds.134

It should be reasonably clear that ring-fencing certain activities does nothing to insulate them from shocks in the financial system. If the financial system suffers a shock, that shock will be manifested in the value of the assets held by financial institutions, the extent of the impact will depend on the composition of the asset book of the institution concerned, and the Vickers report has almost nothing to say about the riskiness of the asset portfolio of the ring-fenced institutions.135 Thus we seem to conclude that the primary justification for the creation of a Vickers-style ring-fence is to facilitate resolution, enabling the retail banking part of the enterprise to be separated out and rescued.

Liikanen-style separation

The section of the Liikanen report which summarises the objectives of its structural separation proposals reads as follows.

The central objectives of the separation are to make banking groups, especially their socially most vital parts (mainly deposit-taking and providing financial services to the non-financial sectors in the economy) safer and less connected to trading activities; and to limit the implicit or explicit stake taxpayer has in the trading parts of banking groups. The Group’s recommendations regarding separation concern businesses which are considered to represent the riskiest parts of investment banking activities and where risk positions can change most rapidly. Separation of these activities into separate legal entities is the most direct way of tackling banks’ complexity and interconnectedness. As the separation would make banking groups simpler and more transparent, it would also facilitate market discipline and supervision and, ultimately, recovery and resolution.

This piece of text proceeds on the unexamined assumption that retail deposit taking is somehow “less risky” than market-based activities, and we will return to this topic in section 4. However, even assuming it were possible to separate a bank into “more risky” and “less risky” activities, it should be relatively obvious that separation of activities conducted within an institution into separate booking vehicles will not improve transparency or market discipline, since these ends are achieved by disclosure requirements and not by legal restructuring. However, if we approach the report in a sympathetic spirit and try and identify what the thought was which animated the conclusion, what appears to come through is the idea that in the public mind the customer should perceive the group as two entities rather than one, be aware of which entity he has contracted with, and be comfortable that it is possible for one of these entities to fail without his claim on the other being affected.

2. The US Experience

The enthusiastic proponents of structural separation in Europe seem to have been unaware that what they were propounding was, and had been for many decades, the state of affairs in the United States. The US regime is based on two ring-fences. The broader ring-fence is set out in the Bank Holding Company Act 1956, which effectively sets a ring-fence around the banking group and determines what any member of that group may and may not do.136 The narrower ringfence is the bank charter itself. This is the charter granted to the bank subsidiary of a bank holding company, and this limits what the bank itself and its subsidiaries may do.137 The effect of these limitations is to confine the bank itself fairly strictly to deposit-taking, lending and money-market activities, with the consequences that other activities – notably securities trading – must, to the extent that they are permitted within the group at all, be carried out within the non-bank part of the group. In order to give effect to these sections 23A and 23B of the Federal Reserve Act place strict limits on the transactions which may be entered into between the bank and its subsidiaries (generally referred to as the “bank chain”) and the other members of the group (the “non-bank chain”)138. The purpose of the 23A/23B regime was (and is) to prevent the activities of the nonbank chain receiving any cross-subsidy from the bank, on the basis that since the bank’s cost of funding is effectively subsidised through the existence of FDIC and deposit insurance, the benefit of that subsidy should be retained within the bank for the purpose of minimising losses to depositors (preservation of competitive equality between free-standing securities firms and bank securities trading subsidiaries was also a concern).

It is fair to say that the fact this fact remained as unknown in Europe after the crisis as it was before the crisis suggests that the separation itself may not have been a major factor in addressing the crisis. The idea that the problems at (say) Citibank could have been usefully addressed by separating the entity into its bank and its non-bank components and resolving the two separately does not appear to have been seriously considered by any relevant authority at any time, and it is not too hard to see why.

3. Separating Market Risk and Credit Risk

It was noted above that a canonical belief of the Liikanen group was that “the trading parts of banking groups” are somehow more risky than the other parts. At first sight this proposition seems counter-intuitive. Even leaving aside the fact that the riskiness of a bank is a function of the composition of its asset book, risk in investment banking is generally monitored and controlled far more carefully than risk elsewhere in a bank. It is notable in this context that the investment banks in the crisis survived fluctuations in asset values which would have flattened a conventional bank, and the reason for this is that investment banks, unlike conventional banks, hedge almost every aspect of their portfolios.

The problem which was encountered during the crisis is that market-based activities are exceptionally vulnerable to market failures. The primary characteristic of investment banking which distinguishes it from commercial banking is –in theory – that the assets and liabilities of an investment bank are marked to market – including, importantly, for regulatory capital purposes. It is now generally accepted that, whatever the cause of the crisis is believed to be, one of the most important factors leading up to it was the idea that markets had moved away from irrational boom and bust cycles and towards a modern, scientific world in which participants would always be prepared to purchase assets at the mathematically modelled “correct” valuation, and that liquidity would therefore always be available at that valuation. The construction of a financial system based on that model meant that when the market did return to boom and bust, the resulting swings in market prices were literally inconceivable to those who had built the models. This problem was compounded by the fact that the liquidity whose perpetual continuation had been so confidently predicted stubbornly refused to appear. This created a vicious circle which drove prices even lower, since buyers will not buy, no matter what the valuation, if they have no money to buy with.

The impact of a market crash has a real-time impact on the capital position of a bank which holds mark to market assets. In particular, the fact that the market has disappeared, or can be accessed only at rock-bottom prices, results in a wholesale destruction of value on the accounting and regulatory balance sheet of the institution concerned. Viewed from this perspective a business which holds mark to market assets can do enormous damage to a bank balance sheet simply by existing, regardless of how well or badly it is run.

Given this, it is worth examining the nexus between trading losses and credit losses to see whether the combination of the two activities in the same entity provides a transmission mecha...

Table of contents

- Institute for Law and Finance Series

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- The Authors

- Introduction

- Cutting the Gordian Knot or splitting hairs – The debate about breaking up the banks

- “What kind of financial system do we want – A global private sector perspective”

- Rescue by Regulation? Key Points of the Liikanen Report

- Bank Structural Reform and Too-big-to-fail

- The Volcker Rule

- Confronting the Reality of Structurally Unprofitable Safe Banking

- Ten Arguments Against Breaking Up the Big Banks

- Structural Solutions: Blinded by Volcker, Vickers, Liikanen, Glass Steagall and Narrow Banking

- Structural Separation and Bank Resolution