![]()

Part I: Philosophy: Varieties of Being

![]()

Chapter 1

Existential semiotics today: Sein (Being) and Schein (Appearing)

1.1 Introduction

Most readers of this book probably know existential semiotics as a relatively new “school” or approach to general semiotics and philosophy. It is intended to renew the epistemic foundations of the theory of signs by rereading the classics of continental philosophy in the line of Kant, Hegel, Schelling, Kierkegaard, Heidegger, Jaspers, Arendt, and Sartre. Its most salient aspect is the revalorization of subject and subjectivity, from which it launches new notions such as transcendence, Dasein, modalities, values, Moi/Soi, and other issues soon to be discussed. It constitutes a kind of ontological semiotics starting from the modality of Being and shifting toward Doing and Appearing, as well. Those who have followed the unfolding of existential semiotics may find the latter of these modalities – Appearing – to be a more recent addition to our line of thought, at least as expounded with the thoroughness it receives here. To prepare for its exposition, let us begin with the most important aspects of existential semiotics.

The mere notion of an “existential” semiotics evokes many issues in the history of ideas and the study of signs1. As such, it is a new theory of studies of communication and signification, as Eco has defined the scope of semiotics (Eco 1979: 8). But beyond that, the attribute “existential” calls on a certain psychological dimension – namely, existential philosophy and even existentialism. As such, the theory involves the phenomenon of transcendence, which may bring to mind American Transcendentalist philosophers, such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, the writer Henry David Thoreau; certainly these and others can be considered kinds of pre-existentialist thinkers. On the other hand, it certainly carries a philosophical tinge that takes us back to German speculative philosophy, to the time of Kant, Schelling, Hegel, and thereafter the existentialist line in the proper sense (i.e., Kierkegaard, Heidegger, Jaspers, Sartre, de Beauvoir, Arendt, Wahl, Gabriel Marcel, etc.). Yet, while the present theory draws inspiration from these classical sources, one cannot return to any earlier historic phase. The theoretical thought of 2015 is definitely philosophy in the present time, and in our case it is enriched by the development of semiotics, particularly throughout the twentieth century.

1.2 A return to basic ideas

The present theoretical and philosophical reflections start from the hypothesis that semiotics cannot forever remain focused on the classics from Peirce and Saussure to Greimas, Lotman, Sebeok, and others. Semiosis is in flux and reflects new epistemic choices in the situation of sciences in the 2000s. Hence my own “return” to existentialism is not bound to classical Hegel, Kierkegaard, Sartre, or Heidegger, but rather it draws inspiration from them and, most of all, situates their ideas within a semiotics of the present.

Existential semiotics explores the life of signs from within. Unlike most previous semiotics, which investigates only the conditions of particular meanings, existential semiotics studies phenomena in their uniqueness. It studies signs in movement and flux, that is, as signs becoming signs, and defined as pre-signs, act-signs and post-signs (Tarasti 2000: 33). Signs are viewed as transiting back and forth between Dasein – Being-There, our world with its subjects and objects – and transcendence. Completely new sign categories emerge in the tension between reality, as Dasein, and whatever lies beyond it. Completely new sign categories emerge. We have to make a new list of categories in the side of that once done by Peirce. Such new signs so far discovered are, among others, trans-signs, endoand exo-signs, quasi-signs (or as-if-signs), and pheno- and geno-signs.

1.3 Modalities

In my earlier theory of musical semiotics (Tarasti 1994: 27, 38–43), I concluded that music signifies most importantly by means of its modalities, in the Greimassian sense. Greimas started with his Sémantique structurale (1966), which stemmed from phenomenology, semantics, Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology, and Lévi-Straussian structural anthropology, not to mention Saussure and Hjelmslev. He launched new concepts such as semanalysis, the actantial model, isotopies, and so forth. In the late 1970s he put his thought into a generative model (“generative course”), which proved both powerful and fashionable at that time (Greimas 1979: 157–164). The most radical of his innovations, however, was the discovery of modalities, to which he referred as the “third semiotic revolution” (the first being the invention of semantics by Bréal, and second, the structural linguistics of Saussure). Modalities are the ways in which a speaker animates and colors his/her speech by providing it with wishes, hopes, certainties, uncertainties, duties, emotions, and so forth. Larousse’s French Dictionary defines modality:

Psychic activity that the speaker projects into what he is saying. A thought is not content with a simple presentation, but demands active participation by the thinking subject, activity which in the expression forms the soul of the sentence, without which the sentence does not exist.

Modalities appear in the grammar of some languages as modal or special subjunctive verb forms. For instance, in French: when one says, “I have to go to the bank”, the sentence is rendered “Il faut que j’aille à la banque”, the verb form indicating the modality of obligation or duty – “must” (devoir) – instilled in the communication by the locution “Il faut” (it is necessary). The “plain”, unmodalized form would be simply “je vais”, you go. Italian and German are two other modern languages that feature the subjunctive mood (modality).

The fundamental modalities are Being and Doing. We further distinguish a third modality, Becoming, which refers to the normal temporal course of events in our Dasein or life-world (discussed below). Other modalities, in turn, are Will, Can, Know, Must, and Believe. Here the modalities are to be understood as processual concepts. They are the element of “classical semiotics” that remains valid in the new existential semiotics, precisely because of their dynamic nature.

1.4 Dasein and transcendence

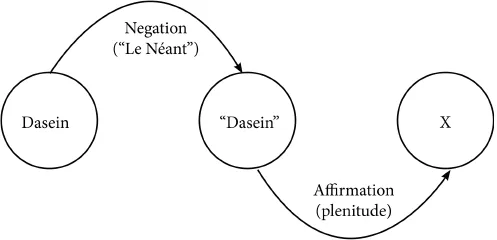

The modalities aptly portray what happens inside what I call Dasein in the model shown in Figure 1.1 (from Tarasti 2000: 10). The concept of Dasein, a term that literally means “being-there”, has been borrowed from German philosophy, especially that of Heidegger and Jaspers (see Jaspers 1948: 6–11, 57–66, 295). Unlike in Heidegger, for whom Dasein refers primarily to my existence, here it does not refer only to one subject, Me, but also to Others, and likewise to the objects of our desire.

Beyond Dasein, beyond the concrete reality in which we live, there is transcendence. The simplest definition of this intriguing notion might be the following: The transcendent is anything that is absent in actuality, but present in our minds.

Figure 1.1: The Model of Dasein

The model also introduces an element crucial to any existential theory: the subject. This subject, dwelling in Dasein, feels it to be somehow deficient or otherwise unsatisfactory, and so negates it. This is what Jean-Paul Sartre called néantisation (Sartre 1943: 44–45). A lack in his/her existence forces the subject to search for both something more and something different. There are two transcendental acts in the model, first negation and then affirmation. With this we have the existential “move” in Dasein (x).

First our subject finds himself amid the objective signs of Dasein. Then the subject recognizes the emptiness and Nothingness surrounding the existence from which he has come – that which precedes him and comes after him. The subject then takes a leap into Nothingness, into the realm of le Néant, described by Sartre. From here, all of his earlier Dasein seems to have lost its foundation: it appears to be senseless. This constitutes the first act of transcendence: negation. The subject does not stop here, but there follows the second act of transcendence, when he encounters the opposite pole of Nothingness: a universe that takes on meaning in some supra-individual way, independently of his own act of signification. This act, affirmation, results in the subject finding what Peirce called the Ground. It was at first difficult to find a suitable concept to portray this state. Upon reading the Russian philosopher Vladimir Solovyov (1965: 348– 349), it became clear that affirmation is what in Gnostic philosophy was called pleroma or plenitude. This in turn evoked Emerson’s notion of the “Oversoul” and Schelling’s Weltseele, world soul. The latter, a kind of anima mundi, refers to the unified inner nature of the world, understood as a living being with the capacity to desire, conceive, and feel. In short, the world soul constitutes a “modal” entity, to use our Greimassian vocabulary (Greimas 1979: 230–232).

It must be emphasized that the present model is of a conceptual nature, not an empirical one. This does not of course exclude it from subsequent psychological, anthropological, or theological applications. One person has proposed that “transcendental journey” means “a psychedelic trip”; others have compared it to the act of a shaman in which his soul, after he has eaten hallucinogenic mushrooms, makes a trans-mundane journey to other realities; and so forth. Our scheme, however, is philosophical and deals with what Kant called the transzendental rather than the transzendent (Kant 1787 [1968]: 379).

We can provide the logical operations of affirmation and negation with psychological content and distinguish more subtle nuances of these acts:

Negation, for example, may mean the following:

Abandonment, giving up: One is in a situation in which x appears; the subject has taken it into its possession but now abandons it, i.e., becomes “disjuncted” from it (formalized as S V O, in Greimassian semiotics; see Greimas 1979: 108).

Passing by: x appears but the subject passes it by.

Forgetting: x appeared, but it is forgotten; it no longer has any impact.

Counter-argument: x appears, but something totally different follows: y; or x appears and is followed by its negation (inversion, contrast, opposition, etc.). This corresponds to Greimas’s semiotic square and its categories s1 and s2, and non-s1 and non-s2 (ibid.: 29–33).

Rejection: x appears, but it is rejected.

Prevention: x is going to appear, but is prevented from doing so.

Removal of relational attributes: x appears, but one eliminates its semes x … xn, whereafter it becomes acceptable.

Destruction: x appears, but is destroyed.

Collapse, disappearance: x appears but disappears on its own accord, without our being able to influence it.

Concealment: the appearance of x is hidden, but it nevertheless “is” on a certain level.

Parody: x appears, but it is not taken seriously, or is taken as an “as-if”.

Mockery: x appears, but one trifles with it; it is ironized, made grotesque.

Dissolution: x appears, but it is reduced to smaller parts; when its total phenomenal quality is lost, one “cannot tell the forest from the trees”. In Adorno’s words: “When one scrutinizes art works very closely, even the most objective works turn into confusion, texts into words […] the particular element of the work vanishes; its abridgment evaporates under the microscopic gaze” (Adorno 2006: 209, translation mine).

Misunderstanding: x appears, but it is not interpreted as x, but as something else.

Affirmation, in turn, may mean the following:

Acceptance: x appears and we accept it without intervening in it; for example, when we rejoice in others’ success.

Helping: We may contribute to the fact that x appears.

Enlightenment: We see x in a favorable light.

Revelation of the truth and disappearance of the lie: x appears, and it is recognized as Schein (mere appearance, a lie); conversely, we act in such a way that allows x′ to appear.

Initiation: We start to strive; we undertake an act so that some positive, euphoric x appears.

Duration: We attempt to maintain x; for example, by teaching someone.

Completion: x appears as the final result of a process, as the reward of pain; Schein, now in the sense of “shine” or brilliance, has been attained by labor. We say more about this later, concerning the modality of Appearing (apparence).

Organic vitality: x erupts; it appears in consequence of an organic process, as having abandoned itself to the process, as if “riding atop a wave”.

Transfiguration: x radiates something that stems from the background, not from its own power, but as the effulgence of an invisible reality. For example, take the bodies in El Greco’s paintings. First we encounter the negation – a body portrayed as suffering – but behind it a hopeful luminosity.

Victory: x appears as the end of a long struggle; for example, the brilliant C major at the end of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony in C minor.

Opening: the appearance of x means a gateway to possibilities; new worlds open to us.

Liberation: the appearance of x signifies a breaking of the chains of y or x′.

1.5 Turn-around of Dasein

Two other aspects of this model relate to how our psyche adapts to his/her existential situation and journeys. The first of these is evoked by viewing negation as a kind of alienation or estrangement: when a subject temporarily exits his Dasein in his transcendental act, the journey can last for whatsoever time span, be it hours, days, weeks, even years. And it can happen that when he returns to the world of his Dasein, he finds it changed. Like a spinning globe, it has continued moving on its own and completely apart from our subject; it has perhaps turned in such a direction that, when our subject returns, it is no longer the same world. One may find in our model the solipsism that Dasein exists only for one subject and that it changes its shape because of his/her existential experiences. But not only so. For during the transcendental journey, the world may have in the meantime developed in a new direction. The subject does not return “home” but to a quite different world from the one that he left. Insofar as we take Dasein as a collective entity, which consists of subjects and objects, of Others, we encounter the community and the autonomous development of the collectivity, the changes brought by history. Our subject can either accept this change and tr...