![]()

1 Introduction

1.1 Object of study and preliminaries

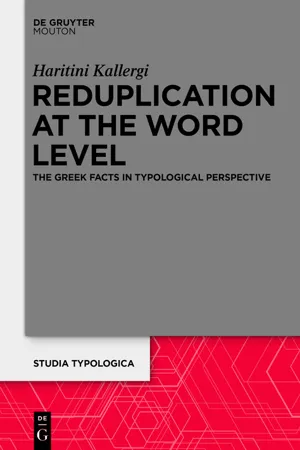

This dissertation focuses on types of expression in Modern Greek (MG onwards), typical examples of which are the following:

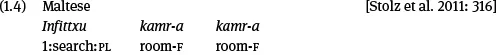

‘S/he went downtown to the market (very) early in the morning.’

‘We watched the film piece by piece.’

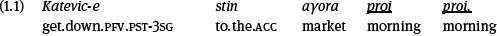

Examples (1.1) and (1.2) share several characteristics with the following examples, the one from a non-European language and the other from a European one:

pagi morning > pagi-pagi ‘early in the morning’

‘we will search each room (= room by/after room)’

The lines along which the MG examples are similar (or even parallel) to examples (1.3) and (1.4) have to do with both formal and functional aspects of the expressions in question. Form-wise, in all examples there are two instances of a word, which are morphologically identical and are not interrupted by any other word or morpheme. The two copies of the word also seem to be located in the same syntactic domain (i.e. with the exception of (1.3), they are all found within a single clause and/or sentence) and, as is particularly evident in example (1.4), they are identical syntactic realizations (or word-forms) of the same lexeme (see section 1.1.1 below).

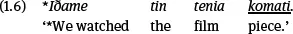

In terms of function, all examples share the following trait, best shown by the Indonesian example: between the single and the double occurrence of the word, there is some semantic or grammatical information added. That is, the “(very) early” and the “by/after” parts of the interpretation of the expressions seem to be added by means of doubling the word, instead of being offered by some element in the vicinity of the doubled words. In fact, this information can only be brought about by the doubling, since the versions of the examples with a single occurrence of the word (1.5 and 1.6 below) are either semantically different or ungrammatical in comparison to (1.1) and (1.2):

Moreover, the meanings conveyed by such expressions are parallel between examples (1.1) and (1.3), as well as between (1.2) and (1.4): the first pair expresses a kind of intensity (given that the morning is considered the first or an early part of the day), whereas the second pair signals an event of distribution or segmentation.

Having given a sketchy description of the above examples, I claim that they all form instances of Total Reduplication (TR onwards), as delimited and described by Stolz (2003/04; 2007b) and Stolz et al. (2011). According to Stolz (2003/04: 13), the first (provisional) criterion for assuming a category of TR in a language is that the reduplication of a word or a word group occurs within the utterance of a single speaker, without allowing a syntactic boundary or the intercalation of other elements between the double words. Also, the copies of the word/word group must be identical and only two, they must belong to the same breath unit, and should together have a meaning that is not fully identical to the meaning of the single word/word group (Stolz 2003/04: 13). Stolz et al. (2011) refine the above criteria, offering the characteristics of the prototypical TR instance: the copying is complete and exact, the copies are contiguous and continuous (uninterrupted), and the base of the copying process is morphologically complex, i.e. it consists of “fully functional syntactic words […] with their full array of inflectional and derivational morphemes” (Stolz et al. 2011: 53). Based on cognitive and semiotic principles, Stolz et al. (2011: 39–57) in fact argue that the above features (that constitute the profile of word-external or “syntactic TR”, Stolz et al. 2011: 69) make up the prototype of all reduplication phenomena.

But what is reduplication?

The term reduplication can be generally used in two senses. Under a very broad view, it may refer to the reappearance of any kind of linguistic material, from phoneme to clause, which occurs within a limited framework (from a word to a text in discourse) and serves various purposes. In fact, in this sense, reduplication may be considered a synonym for repetition or iteration (see section 1.3 for various types of reduplication in this sense). Also in this sense, every language can be considered to exhibit reduplication of some kind (see, e.g., Kakridi-Ferrari 1998: 1).

On a much narrower view, reduplication (and not repetition or iteration) refers to the “systematic repetition […] of an entire word, word stem […] or root … for semantic or grammatical purposes” (Rubino 2005: 11). The domain of this repetition is argued by Rubino to be “the word”, i.e. even the reduplication of an entire word has to lead to another word. On this view, reduplication is essentially a “morphological device” (Rubino 2005: 11, see also, e.g., Booij 2005; Forza 2011). As such, according to Rubino’s typology and common belief, reduplication is not attested in languages such as MG, where the morphological reduplication for the formation of the perfect (as in Classical Greek, e.g. λύω > λέ-λυκα ‘solve’ > ‘have solved’) is no longer productive (Rubino 2005: 13, 22).

However, it is in fact arguable whether the reduplication of an entire word, widely called total or full reduplication, always occurs “within a word”, as Rubino claims. First, if the result of the reduplication (viz. the two “words”) carries group inflectional or derivational affixes, the input may be regarded as stem (hence, there is no “reduplication of an entire word”). Second, total reduplication (as presented in Rubino and elsewhere) does not always have the form of a single orthographic unit, but the words may stand separated, and it is not certain whether the X(-)X group fully behaves as a single word for the speakers of the language in which total reduplication of the X(-)X type is found. Thus, it becomes clear that TR, as the reduplication of full words, is dependent on the notion of word and thus comprises a problematic case of reduplication in the narrow sense of the term.

It is perhaps useful at this point to make a short digression in order to refer more clearly to the problem of the definition of the word. At the same time, I will clarify the senses of the term (or the “types” of word) that are relevant to this dissertation.

1.1.1The word

So far in the history of linguistics, it has been admitted that the word is a problematic notion and one that is difficult to define. As Matthews (1991: 208) aptly puts it: “there have been many definitions of the word, and if any had been successful I would have given it long ago, instead of dodging the issue until now.”

More concretely, Haspelmath (2011) convincingly argues (bringing evidence from a great variety of languages) that all the criteria by means of which the word is traditionally or practically defined do not hold on a universal basis (and they sometimes clash within the same language). Thus, if one accepts that the most widely-used notions or aspects of the word are the orthographic word, the phonological word and the grammatical (or morphosyntactic) word (see below), there is evidence that word segmentation across languages cannot be consistently and unambiguously based on these notions.

Roughly speaking, the problem with the orthographic word is that it is a traditional convention established (and biased) through the long-standing writing systems of Western languages (Haspelmath 2011: 36). The phonological word is based on criteria that largely work on their own right (i.e. without converging with grammatical criteria in order to describe a single unit that can be called word) and it may even refer to phonological domains that do not converge within the same language (Haspelmath 2011: 37). As for the morphosyntactic word, a large number of criteria have been proposed or used. External mobility, internal fixedness and uninterruptibility, anaphoric islandhood, non-extractability of parts and morphological idiosyncracies are perhaps the most widespread ones. However, none of these criteria can strictly distinguish words from affixes and clitics or words from syntactic phrases (Haspelmath 2011: 38–60).

Haspelmath (2011: 60) concludes that since there can be no valid, universal notion of word, we cannot rely on such a notion in order to distinguish between morphology and syntax (proposing instead that we view these two components of analysis as a fuzzy area, un...