![]()

IIIInput-related cognitive effects in code-mixing

![]()

Nikolay Hakimov

Effects of frequency and word repetition on switch-placement

Abstract: This contribution investigates the effects of co-occurrence frequency and repetition priming, or recency, on the structure of naturally occurring bilingual speech. It explores, by way of a case study, patterns of insertional code-mixing in a spoken Russian-German bilingual corpus. In insertional code-mixing, stems from one contact language (embedded language) regularly appear in sentences framed by the other contact language (matrix language) and receive morphosyntactic marking from that language. The resultant mixed constituents alternate with longer embedded-language constituents, usually referred to as ‘embedded-language islands’ (Myers-Scotton 1993; Auer 2014). In the context of the prepositional phrase, the Russian-German bilingual speaker thus has a choice between inserting a German noun into a Russian prepositional phrase or producing a fully-fledged German prepositional phrase embedded in a Russian clause. The study provides tangible evidence that this choice depends on (i) the frequency with which the examined nouns are used together with specific prepositions in monolingual German, (ii) the degree of competition among these prepositions in monolingual German, and (iii) the occurrence / non-occurrence of the relevant prepositions in prior discourse, i.e. repetition priming.

Keywords: frequency of use, recency, priming, competition, prepositional phrase, code-mixing/switching, embedded-language island, Russian Germans, bilingual speech

1Introduction

Much research in recent years has focused on the frequency of linguistic structures as a major factor affecting human linguistic behaviour and language organisation. Studies in language acquisition, language processing and language change have accumulated a wealth of evidence that probabilistic information about distributions of linguistic structures is an intrinsic part of language organisation (Barlow and Kemmer 2000; Behrens & Pfänder 2016; Bybee and Hopper 2001; Divjak and Gries 2012; Gries and Divjak 2012; see Diessel 2007; Ellis 2002 for reviews). Both psycholinguistic experiments and analyses of natural spoken language corpora report that (monolingual) language production is influencedby word frequency (Jescheniak and Levelt 1994) and probabilistic relations between neighbouring words (Janssen and Barber 2012; Jurafsky et al. 2001; Kapatsinski 2010; Schneider 2016), as well as the likelihood of syntactic (Tily et al. 2009) and morphosyntactic (Gorokhova 2009) structures with which the word is used. However, attempts to account for bilingual and multilingual production – particularly patterns in code-mixing – by integrating probabilistic information inherent in the codes are still absent from the literature, despite the constantly growing body of work dedicated to bilingualism and multilingualism.

Furthermore, few current models of bilingual and multilingual production take into account cognitive processes operating in online language production in discourse. Priming, an implicit memory effect defined as the influence of the prior presentation of a stimulus on the processing of a subsequent stimulus, has been shown to affect monolingual production on various levels of language (see Pickering and Ferreira 2008, for a review). In bilinguals, experimental studies have focused on cross-language priming effects in lexical access (Dijkstra, Van Heuven and Grainger 1998; Kroll and Stewart 1994; Van Hell and De Groot 1998) and the production of syntactic constructions (Loebell and Bock 2003; Salamoura and Williams 2006; Schoonbaert, Hartsuiker and Pickering 2007). Only recently has experimental research approached priming effects in code-mixing. For example, Koostra, Van Hell and Dijkstra (2010) find that participants in their experiments tended to switch languages at the same position as in the prime sentence, a finding that was shown, in their later study, to be driven by both the presence of cognates in the prime sentence and word repetition (Koostra, Van Hell and Dijkstra 2012). Analyses of naturally occurring code-mixing have traditionally neglected priming effects5, although the study by Torres Cacoullos and Travis (2016) represents an exception to this trend. The authors assert that in the New Mexico Spanish-English Bilingual corpus, the distribution of syntactic structures in a particular syntactic context – expression of the Spanish first-person singular subject pronoun – largely depends on both language-internal and cross-language priming effects. We can conclude from these few studies that repetition of words and structures in discourse requires due consideration in the analysis of code-mixing. However, the role of repetition in the structure of naturally occurring code-mixing remains unexplored to date.

The purpose of this chapter is to account for patterns of insertional Russian-German code-mixing by taking frequency and word repetition into consideration. In approaching the data, I adopt Auer’s (1999, 2011) distinction between the cases of code-switching and code-mixing. In the case of code-switching, conversation participants perceive and interpret the juxtaposition of two codes as meaningful in each individual instance, whereas in the case of code-mixing, language juxtaposition is meaningful for participants in a global sense, i.e. “as a recurrent pattern” (Auer 2011: 467). The present study examines the placement of a switch in the context of the prepositional phrase, which is one of the most frequently reported loci for code-mixing: a speaker can switch the language either at the boundary of the prepositional phrase (Bentahila and Davies 1983: 314; Boumans 1998: 271, 315; Clyne 1987: 757; Haust 1995: 169; Pfaff 1979: 310; Treffers-Daller 1994: 208, 221–224) or within the prepositional phrase, i.e. between the preposition and the noun phrase (Bentahila and Davies 1983: 315; Poplack 1980: 602; Pfaff 1979: 310; Stenson 1990: 173, 178). This variation, which is also characteristic of Russian-German code-mixing, is approached here as an outcome of several factors. First, switch placement is assumed to be influenced by the frequency of the phrase, as measured in a monolingual corpus. That is, a switch at the boundary of the prepositional phrase is likely when high-frequency preposition-noun combinations are produced. With low-frequency combinations, a switch is more probable between the preposition and the noun. The second considered factor is the frequency of the noun being used in the prepositional phrase, which is also measured in a monolingual corpus. Finally, the lexical material constituting the prepositional phrases is considered subject to repetition priming.

2Previous accounts

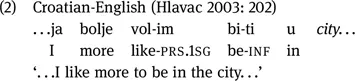

Although code-mixing in the context of the prepositional phrase is widely reported in studies of code-mixing involving various language pairs, few scholars have attempted to account for the observed variation between placing a switch within the prepositional phrase and switching at the phrase boundary. Such variation has been of particular interest to the Matrix Language Framework (MLF) model (Myers-Scotton 1993, 2002). The principal tenet of this model is that the structure of a code-mixed clause can be analysed by determining the division of labour between the involved languages.6 The language responsible for the core clause structure is called the matrix language (ML); the other, dominated language, whose role is usually restricted to the supply of lexical items, is the embedded language (EL) (Myers-Scotton 1993: 75–119). As a result of this asymmetry, embedded language content morphemes such as nouns are inserted into constituents framed by the matrix language to form mixed constituents. For instance, in (1), the English noun city is preceded by the Croatian preposition u ‘to’ and takes the inflection -ju of the accusative case, assigned by the preposition, so that a mixed constituent city-ju ‘city-ACC.SG.F’ emerges.

Embedded language noun stems sometimes lack matrix language case markers, as in (2), where the noun city, again preceded by the Croatian preposition u ‘in’, does not take the required locative marker and remains bare.

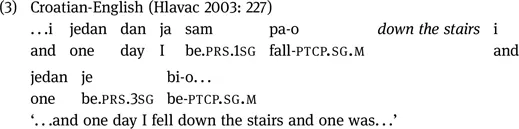

In code-mixing, prepositional phrases consisting of a matrix language preposition and a mixed constituent, as in (1), and those constituted by a matrix language preposition and an embedded language noun (phrase), as in (2), alternate with prepositional phrases containing only embedded language morphemes. Sequences of embedded language morphemes in the matrix language context, such as prepositional phrases, are called embedded language islands. We can thus analyse the English prepositional phrase down the stairs in (3) as an embedded language island.

Myers-Scotton and Jake (1995) explain the appearance of embedded language islands in code-mixed utterances in terms of the premise that grammatical information contained in lemmas (i.e. entries in the mental lexicon underlying lexical items) is distributed at three levels: (i) lexical-conceptual structure (semantic/ pragmatic features), (ii) predicate-argument structure, and (iii) morphological realisation patterns. The lack of congruence at one of these levels between the relevant embedded language lemma and its matrix language equivalent can result in the emergence of an embedded language island (Myers-Scotton and Jake 1995: 1008–1014). According to Hlavac (2003), the embedded language island in (3) is produced because the content morpheme down “for most of its uses in English [. . .] is non-congruent to any Croatian content morpheme equivalent” (p. 227). In other words, the lemmas involved do not match at the level of lexical-conceptual structure. At the same time, Deuchar (2005: 258) contends that semantic/pragmatic differences between lemmas, as in (3), can motivate the appearance of switches, but only grammatical congruence enables code-mixing. In the case of prepositional phrases it is thus congruence at the level of morphological realisation patterns that is relevant in the first place. Different realisation patterns of adposition indeed seem to determine the emergence of embedded language islands in certain language-pairs. For instance:

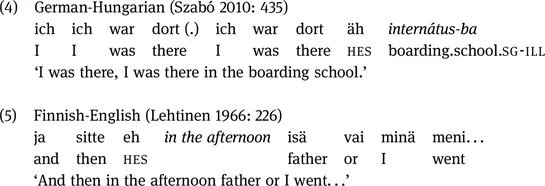

The Hungarian illative suffix -ba in (4) expresses the kind of spatial relations that are coded by the preposition in in German. Hence, the Hungarian phrase internátusba ‘in the boarding school’ corresponds to the German prepositional phrase im Internat (where im is a contracted form, merging the preposition in and the determiner dem). The phrase in the afternoon in (5) is equivalent to the Finnish iltapäivällä, which consists of the noun iltapäivä ‘afternoon’ and the adessive suffix -llä.We can thus conclude that, if one of the languages involved in code-mixing employs preposi...