eBook - ePub

Language Change in Central Asia

- 289 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Language Change in Central Asia

About this book

Twenty years after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan are still undergoing numerous transitions. This book examines various language issues in relation to current discussions about national identity, education, and changing notions of socio-cultural capital in Central Asia.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Language Change in Central Asia by Elise S. Ahn, Juldyz Smagulova, Elise S. Ahn,Juldyz Smagulova in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Juldyz Smagulova and Elise S. Ahn

1 Introduction

1 Overview

In the foreword to the second edition of the classic, The Great Game, Peter Hopkirk (2006: xiii) wrote that “[s]uddenly, after many years of almost total obscurity, Central Asia is once again in the headlines, a position it frequently occupied during the nineteenth century, at the height of the old Great Game between Tsarist Russia and Victorian Britain”. The unexpected dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the subsequent socio-political reforms developed in each of the then newly independent Central Asian countries, and the continued broader geo-political instability has turned the area back into a “hot spot” drawing the attention of policy makers, social scientists, academics, and journalists.

Narrowly, Central Asia (sometimes referred to as Central Eurasia) geo-politically consists of the former Soviet Union (FSU) Turkic republics, which includes Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, along with Tajikistan. However, when taking into consideration transnational minorities and historical population migration patterns, a broader conceptualization of Central Asia could include parts of Western China (e.g., Xinjiang), southern Siberia, the East European Plains, Afghan Turkestan, and the Pamiri and Kashmiri regions which straddle Tajikistan and Afghanistan (Figure 1.1). This book looks at Central Asia through both lenses, narrow and broad, in an attempt to delineate the different pathways the republics have followed as well as elucidating cross-national language and education-related issues.

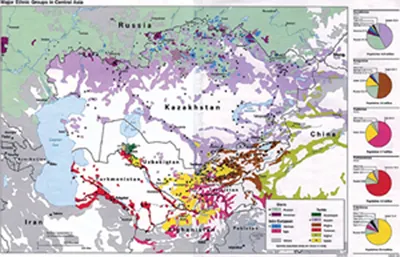

The linguistic map of the modern Central Asian region displays enormous diversity and complex interaction patterns between the indigenous Turkic and Iranian languages and the Russian language (Figure 1.2). Many communities are historically multilingual, e.g., the Tajik-Uzbek-Russian speakers of Samarkand, Uzbekistan or the Kazakh-Uyghur-Chinese speakers of Kulja, China.

However, despite the region’s importance geo-politically and historically, empirically-based research on Central Asia is still in a nascent stage. Particularly regarding language-related research, language change efforts vis-à-vis numerous language change reforms “went largely unnoticed by the linguistic community” and many processes that could enrich sociolinguistic research were left undocumented and unanalyzed (Pavlenko 2013: 263).

Twenty four years after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the region is still undergoing numerous socio-economic and political changes. A top priority for the national governments is their establishment as independent and legitimate political and global entities. Equally important is the construction of national identities. An added layer of complexity is the continuation of the political maneuvering from the international community that took place during the last few centuries, i.e., the “Great Game” which continues today in soft power domains, e.g., economics, language, and culture. These external and internal power dynamics are further complicated by the enormous challenges that these countries are facing including: ethno-linguistic and religious conflict, security, population movement, poverty, unemployment, and increasing social stratification.

Figure 1.1: A map of Central Asia and its neighbors

Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Caucasus_and_Central_Asia_-_Political_Map.webp

Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Caucasus_and_Central_Asia_-_Political_Map.webp

Figure 1.2: The ethnolinguistic patchwork of Central Asia in the later years of the Soviet Union

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soviet_Central_Asia#/media/File:Central_Asia_Ethnic.webp

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soviet_Central_Asia#/media/File:Central_Asia_Ethnic.webp

To illustrate the complex geo-political and sociolinguistic dynamics in the region, one can look at the case of the Russian language. The sharp decline of Slavic and Russian-speaking population in Central Asia, in conjunction with the widespread de-Russification policies in the newly formed states has significantly decreased the cultural influence of Russia in the region. There has appeared a whole new generation of locals particularly in rural areas who are monolingual speakers of their titular languages. Despite these demographic changes and policy shifts, the Russian language is still wide-spread; it remains the lingua-franca, the language of pop-culture, mass-media, new media, education, as well as the language of academic and business communication. In fact, Russia’s economic growth and its rising political influence has propelled a resurgence of interest in Russian among local populations (Pavlenko 2013). Russian was also acknowledged as a working language of the newly established Eurasian Economic Union May 2014), further reifying its symbolic capital in the region.

While Russia continues to reassert its influence throughout the FSU countries, other regional actors are pursuing their own agendas in order to gain economic, political and cultural influence in the region. For example, the Chinese government is funding Confucius Institutes throughout Central Asia, while providing funding for Central Asian students to study in China (30,000 scholarships over the next 10 years). The Turkish government and Turkish businessmen are funding Turkish schools and universities, and funding is coming into the region from the Middle East to finance the construction and establishment of Islamic religious schools, i.e., medresses.

While different political actors engage in building ties to and within the region, poverty and high unemployment rates have forced many people to migrate to other places both in and outside of the region, in search of jobs and opportunities. In addition to the language policy and planning efforts that have been established and implemented by the states, this type of labor migration has thus provided additional impetus to learn other languages/dialects for mobility and employment purposes.

These and many other factors (both macro and micro) have informed the political defragmentation process that have been taking place in these linguistically, culturally and socially diverse societies. But in the context of growing social fragmentation, promoting and maintaining a dominant Westaphalian nation-state model (i.e., “one state, one language”) has been difficult for new nation-states in light of issues related inequality, labor mobility, diversity, and change (Heller 2011).

However, while the Central Asian republics share socio-cultural, historical, and linguistic similarities, along with a Soviet legacy that has remained entrenched in various institutions, they have pursued different development pathways. By focusing on language-related issues, this edited volume is thus an attempt to describe the how social change has been conceptualized, implemented, and experienced within and across the transnational complex of the Central Asian republics. Thus, this book broadly revolves around the following questions:

| – | How has the institutionalization of language and literacy policies through education with a focus on affirming titular languages contributing to the reproduction of particular types of national identities or nationalist discourses? |

| – | How do (new) language practices and changing notions of what constitutes socio-cultural-linguistic capital reflect wider global and local, social and cultural changes? |

| – | What has been (and continues to be) the impact of urbanization and demographic change on language change, particularly as it relates to language shift and revival, as well as education reform in Central Asia? and |

| – | How has language been used as a geo-political tool in the politicization of transnational identities and histories (e.g., pan-Turkism, pro-Russian, pro-EU movements)? |

All of the chapters in this book provide insight into one or more of the aforementioned questions in relation to current discussions about national identity, language policy and planning processes, education, and changing notions of socio-cultural capital in the Central Asian context. The overall aim of this book is to encourage discussion about these different lines of research that will contribute to the broader field of the sociology of language by examining this under-published but dynamic region.

2 Context

To situate this volume in terms of language research, this section provides a brief overview of sociolinguistic research on language change in post Soviet countries. Pavlenko (2013) lists several reasons for the scarcity of sociolinguistic research of post-Soviet contexts in the West, particularly in the United States. This includes: a lack of an appropriate methodological foundation for the study of sociolinguistic changes and linguistic reforms in the post-Soviet space; a lack of systematic sociolinguistic fieldwork and an overreliance on surveys and analysis of policy documents; and a lack of collaboration between Western and local scholars (Pavlenko 2013: 263). Similar problems have more generally hindered the development of sociolinguistic research in post-Soviet academia.

Briefly looking at its intellectual history, one of the key assumptions under-girding Soviet linguistic research was the understanding that language was a type of a social activity and that it was dialectically linked to both social consciousness and interaction (Desheriev 1968; Jakubinsky 1986; Krysin 1977; Polivanov 1931; Shveitser 1976; Shveitser and Nikolsky 1978). But despite this conceptualization of language as a social phenomenon contemporary to the work being conducted by Labov (1972a, 1972b) and others, Soviet sociolinguistics was fundamentally constrained by ideology. Because the socialist society was theoretically egalitarian and therefore classless, to posit that language variation could be due to social inequality and/or power differentials or that it was ideologically driven was not permitted. This is exemplified in how the analysis of Soviet researchers regarding language planning in African post-colonial contexts was framed as a critique of urban Western bourgeois policies (and thus aligned with narratives produced by Soviet ideology). Additionally, language planning studies in the Soviet Union advanced the notion that the Soviet language policy was enriching for both the Russian language as well as the milieu of minority languages (Desheriev 1966, 1987; Isayev 1979; Khasanov 1976).

Moreover, foundational to the creation a homogenous Soviet nation was the establishment of Russian as the language of the Union. This process of sblizhenie (getting closer) and sliianie (merging) of ethno-linguistic groups further confined research related to bilingualism and language contact to “safe” areas including comparative linguistics and examining language transfer as it related to the improved acquisition of Russian by non-Russian speaking populations.

Research was also constrained by ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- List of illustrations

- List of tables

- List of abbreviations

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Language Ecology: Understanding Central Asian Multilingualism

- 3 Being Specific About Generalization: Using Ethnographic Interviews to Examine Kyrgyz Habitual Narratives

- 4 Language Teaching in Turkmenistan: An Autoethnographic Journey

- I Language and Nation-State Building

- II Globalization and Language Change in Central Asia

- Appendix

- Index

- End notes