![]()

1 Introduction

1.1 Setting the Stage

In his commemorative inscriptions the Assyrian king Tukultī-Ninurta I (1233‒1197 BCE) relates that, subsequent to his victory over Babylon in 1215 BCE, he transferred his residence from the city of Aššur to his newly founded capital, Kār-Tukultī-Ninurta (figs. 1 and 2).1 The construction of the new royal capital had been under way since the early years of his reign, and the ideological message promulgated by Tukultī-Ninurta sought to link Assyria’s victory over Babylon – the time-honored religious center – with the creation of a new political and religious center in Assyria.2 Tukultī-Ninurta’s extraordinary move from Aššur to Kār-Tukultī-Ninurta included not only the building of a new royal palace, but also the attempt to transfer the cult of the god Aššur away from the city Aššur, an act unique in Assyrian history.3 This audacious development took place when the Middle Assyrian state was at the peak of its territorial expansion, counting for a short time Babylonia among its domains. By exploring the ideological discourse employed by Tukultī-Ninurta I to justify his political decisions, I intend to set the stage for an investigation of the history of the cultural discourse surrounding Assyrian kingship from the late third millennium through to the Neo-Assyrian period. First, however, I will shed light on the rich tapestry of traditions implicated in the naming of Tukultī-Ninurta’s new palace, in order to provide the reader with an inkling of the immense potential of possible insights that the modern scholar can gain from taking such choices seriously.

The building inscriptions commemorating Tukultī-Ninurta I’s move to Kār-Tukultī-Ninurta record the ceremonial names given to the newly built Aššur temple and to the new royal palace. To my knowledge, this is the only known example in which temple and palace share the same name: “house, mountain of all the me” (é.kur.me.šár.ra),4 and “palace of all the me” (é.gal.me.šár.ra)5 respectively. The name of the palace was rendered in Akkadian as bīt kiššati, ‘house of totality.’ This is not a literal translation of the Sumerian ceremonial name, but instead reflects the title “king of totality,” šar kiššati. As such, it recalls an ideology that had emerged under the kings of Akkad,6 and was then reproduced in the ceremonial name for Tukultī-Ninurta I’s palace in Aššur itself, which was called “house of the king, sovereign of the lands” (é.lugal. umun.kur.kur.ra), evoking the Enlilship of Aššur-Enlil.7 I would like to take this onomastic phenomenon as the point of departure for my discussion of Assyrian royal ideology and ask: what did the king and his scholars have in mind when choosing this particular ceremonial name for Tukultī-Ninurta I’s palace in his new residence? How does it relate to their claim of universal control?

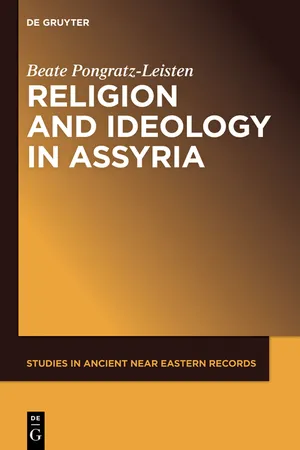

Fig. 1: Socle of Tukultī-Ninurta I (Berlin Vorderasiatisches Museum, Assur 19869/VA 8146; Photo: Aruz, Benzel, and Evans 2008, 210; Drawing: Black and Green 1992, 29).

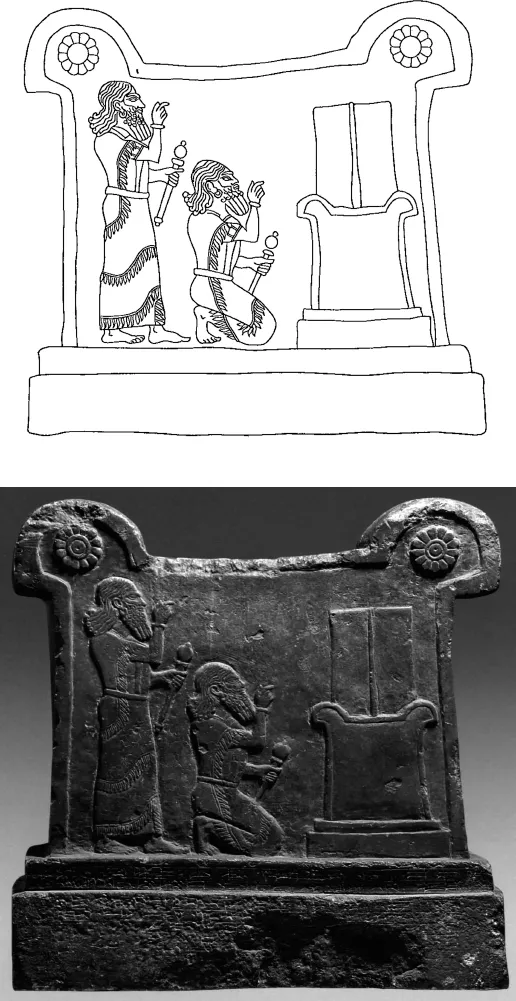

Fig. 2: Socle of Tukultī-Ninurta I with Base Frieze (Photo: Moortgat 1969, fig. 247; Drawing of Frieze: Pittman 1996, 351, fig. 24).

The Sumerian ceremonial name “Palace of All the me” is reminiscent of names given to temples of Inanna/Ištar, who is renowned in Sumerian mythology for stealing the me from her father Enki in Eridu and bringing them to the city of Uruk.8 Among the temple names evoking this myth are the “house which gathers all the me” (é.me.kìlib.ur4.ur4) of the goddess in Larsa,9 the “house which lifts on high all the me” (é.me.kìlib.ba.sag.íl) of Inanna/Ištars messenger Ninšubur at Girsu?,10 the “house of skillfully-contrived me” (é.me.galam.ma), akītu-temple of Ištar at Akkade,11 the “house of scattered(?) me” (é.me.bir.ra),12 a shrine in Aššur’s temple Ešarra at Aššur, and the “house of the me of Inanna” (é.me.dInanna), the temple of the Assyrian Ištar at Aššur, which in the building inscriptions of Tukultī-Ninurta I appears in its abbreviated form é.me.13 All of these Sumerian ceremonial temple names relate in a condensed form to the mythology surrounding the goddess Inanna/Ištar, and the space of the temple as res extensa of her divine body echoes her “biography.” The goddess, her agency, and her lived-in space within the urban landscape of the Mesopotamian cities had merged into one and become part of the cultural landscape of their inhabitants.

As seen by the mythologizing connotations of temple names incorporating the me, Tukultī-Ninurta I’s decision to include the me in the name of his palace was not arbitrary. By referencing the me, Tukultī-Ninurta I demonstrates a desire to connect Assyrian kingship with the divine figure of Ištar. According to the Sumerian myth Inanna and Enki, the me include all the cultural norms, institutions, professions, and positive and negative aspects of human behavior.14 The me also encompass the institution of kingship and its associated insignia, thereby designating Inanna as the patron deity of kingship.15 Although in the later second millennium BCE the meaning of Sumerian me is restricted through its much narrower Akkadian translation as parṣu – “cultic regulation”16 – the choice of the name é.gal.me.šár.ra for Tukultī-Ninurta’s palace implies knowledge of its more inclusive ancient meaning and its association with Inanna/Ištar. The Akkadian rendering of this name as “house of totality” in turn projects control over the conquered world, as well as over those regions of the world with which Assyria interacted through peaceful means, primarily trade and diplomatic arbitration. This notion is explicit in the royal title “king of Kish,” which was iconic as early as the reign of king Mesalim of Kish (ca. 2600 BCE).17 By the time of the kings of Akkade, the title had come to mean ‘king of totality,’ šar kiššati, “using the similarity of the name of the city of Kish and the Akkadian term for ‘the entire inhabited world,’ kishshatum.”18 Tukultī-Ninurta I’s ceremonial name for his new palace, consequently, was intended to promulgate the king’s claim to universal control “by the love” of Innana/Ištar; in other words, the king’s effective empowerment through the grace and goodwill of Inanna/Ištar,19 perpetuating an idea that originated in a Sumerian context and was adapted in subsequent periods. This is clear, for instance, in the tradition regarding the legendary king Etana, in which Ištar seeks a suitable individual to occupy the position of king established by the gods.20

In its highly abbreviated form, the ceremonial name of Tukultī-Ninurta I’s palace thus epitomizes the theological metastructure of Assyrian kingship. The centrality of the goddess Ištar to Assyrian kingship is apparent in the fact that Tukultī-Ninurta I committed himself to building a double temple to Ištar-Aššurītu and Dinītu as soon as he ascended the throne, with Dinītu replacing Bēlat-Akkadî in one version of the building inscriptions.21 To that end, Tukultī-Ninurta demolished the former Ištar temple, justifying this action through the claim that Ištar explicitly communicated her desire for a new building with a different outline.22 Claiming that a specific deity expressed his or her will explicitly is a cultural strategy that we will encounter much later with Sennacherib’s reconfiguration of the Aššur temple in Aššur as well.

In Middle Assyrian times, Ištar had multiple cults dedicated to her various manifestations in Aššur alone, among them those of Anunītu, the Assyrian Ištar (Ištar-Aššurītu),23 Ištar-of-Heaven (Ištar-ša-šamê), Ištar-of-Nineveh (Ištarša-Ninuaki), Ištar-of-Arbela, and her hypostasis as Bēlet-ekalli and Šarrat-nipha.24 All of these Ištar figures shared a bellicose aspect, which bore upon Ištar’s active, though not exclusive, support for the king during military campaigns intended to actualize his control over ‘totality.’ Ištar’s other central aspect is her role as protector of the king, on whose behalf she mediates with the chief god and the divine assembly. The tropes expressing her protection of the king extend from her role as name-giver in Eannatum’s Stele of the Vultures and the Sacred Marriage attested in Sumerian royal hymns25 to her role as nurse and wet nurse of the king in Late Assyrian prophecies. Ištar-Anunītu was introduced in Aššur during the Akkad period, when the kings of Akkad called themselves her ‘favorite’ and her ‘consort,’ and then reintroduced under Tukultī-Ninurta I. It is also during the Middle Assyrian period that we encounter the first evidence for prophetesses in Aššur. The possibility that the institution of prophetesses was similarly (re)-introduced under Tukultī-Ninurta should be kept in mind, as Ištar-Anunītu is well attested in Amorite tradition (Mari in particular) as being a prophesying deity for the king. In any event, all of these tropes share a common emphasis on Ištar’s love for the king.26

In ancient juridical language love signified both the protection of an overlord for his vassal and the loyalty of the vassal to his overlord,27 a view that made its way into Sumero-Babylonian and Assyrian ideological discourse and represents one of the many examples of the close association between religion and law in the ancient Near East. This conceptualization of love constituted one of the most powerful instruments for the legitimization of the king’s occupation of the throne, with the love of Inanna/Ištar guaranteeing the protection and love of the chief god Enlil or Aššur. That this trope enjoyed a broad diffusion through Mesopotamia and Syria is evident also from the archaeological evidence, notably in the close association of the Ištar temple with the palace in Alalah28 and the Old Babylonian representation of the king’s enthronement under the loving supervision of Ištar in Zimrilim’s palace in Mari.29

Ištar-Šauška, a Hurrian hypostasis of the goddess Ištar, played a role in the city of Nineveh equivalent to that of Ištar in her various hypostases in the city of Aššur. This is true at least as early as the time of Šamšī-Adad I (1808‒1776 BCE), as during the Hurrian occupation preceding Šamšī-Adad I’s conquest Ištar-Šauška was the consort of Teššub, heading the Hurrian pantheon together with him. Ištar-Šauška’s supra-regional status is acknowledged by Hammurabi in the prologue to his Law Code30 mentioning her and her city among the places he conquered in the Old Babylonian period. As a supra-regional deity Ištar-Šauška appears again in the international treaties concluded by the Hittites with the Mitanni kingdom and other vassals such as Nuhhašše and the Arzawa Country.31 Hammurabi’s epithet in connection with Ištar of Nineveh is interesting: although he is a contemporary of Šamšī-Adad I, Hammurabi refers to Ištar-Šauška’s temple in Nineveh as é.mès.mès where he “proclaimed the me of Ištar.” After renovating the sanctuary originally built by the Old Akkadian king Maništušu,32 Šamšī-Adad I, by contrast, uses the ceremonial name é.me.nu.è “house of the me, which do not lea...