![]()

Deborah Dahl

1Overview of speech and language technologies

Abstract: This chapter provides a technical overview and description of the state of the art for current speech and language processing technologies. It focuses on the technologies that have been particularly useful in assistive and remediative applications for people with speech and language disorders. The major technologies discussed include speech recognition, natural language processing, dialog management, and text to speech. The chapter also briefly reviews other related technologies such as avatars, text simplification and natural language generation.

1.1Introduction to speech and language technologies

Speech and language technologies are technologies that allow computers to perform some of the functions of human linguistic communication – including recognizing and understanding speech, reading text out loud, and engaging in a conversation. Although human abilities to communicate with each other far outstrip the current state of the art in speech and language technologies, the technologies are progressing rapidly and are certainly suitable for application to specific, well-defined problems. There will not be a single, all-encompassing, spoken language understanding system that can be applied to every situation any time soon, but if we look at specific contexts and needs, there very well may be ways that these technologies in their current state can be extremely helpful.

The technologies that will be discussed in this chapter do not in most cases serve those with speech and language disorders directly. Rather, these technologies are more typically deployed to supply speech- and language-processing capabilities as part of applications that, in turn, are specifically dedicated to these populations.

The entire field of speech and language technologies is very broad and can be broken down into many very specialized technologies. We will focus here on the subset of speech and language technologies that show particular promise for use in addressing language disorders. The main focus will be on speech recognition (sometimes also called speech-to-text), natural language understanding, and dialog systems. However, other emerging technologies such as text simplification and natural language generation can potentially play a role in addressing speech and language disorders, so these technologies will also be mentioned briefly.

We will primarily be concerned with applications of the technologies in assistive and remediation situations. However, some of the technologies can also be applied toward other goals, for example, automatic assessment of users’ capabilities and automatic logging and record keeping for clinical and research purposes. We will also touch on these types of applications.

We will focus in this chapter on the technologies themselves, regardless of how they are used in specific applications or research projects, noting that in almost every case, basic technologies will be combined with other software (and hardware) to create specific applications.

Because speech and language technologies are modeled on human capabilities, it is useful to discuss them in the context of a complete system that models a human conversational participant; that is, an interactive dialog system. Conversations between people go back and forth between the conversational participants, each participant speaking and listening at different times. This back-and-forth pattern is called turn-taking, and each speaker’s contribution is called a turn. In the majority of normal conversations, each turn is more or less related to the previous speaker’s turn. Thus, participating in a human-human conversation requires skills in listening, understanding, deciding what to say, composing an appropriate response, and speaking. These skills are mirrored in the technologies that are used to build spoken dialog systems: speech recognition, natural language understanding, dialog management, natural language generation, and text-to-speech (TTS). For people with speech and language disorders, then, these separate technologies can potentially be applied to compensate for disorders that affect each of these skills.

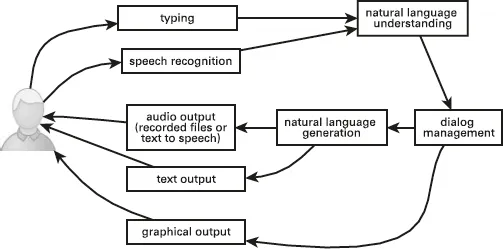

Figure 1.1 is an example of a complete interactive dialog system. A user speaks or types to the system, then the natural language understanding component processes the user’s input and represents the input in a structured way so that it can be used by a computer. The dialog management component acts on the user’s input and decides what to do next. The next action might be some kind of response to the user, interaction with the user’s environment, or feedback to the user on their input. Unlike conversations between people, where the responses will almost always be linguistic, responses in an interactive dialog system can also be in the form of displayed text or graphics.

Fig. 1.1: Complete interactive dialog system.

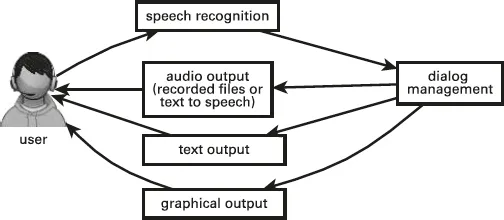

As we will see in the rest of this book, these technologies can be mixed and matched in a variety of ways in different applications to address different remediation or assistive goals. As an example, Fig. 1.2 shows a simpler version of a spoken dialog system, designed to provide the user with feedback on their speech or on individual spoken words. It does not attempt to provide the user with feedback on language, so it does not require a natural language understanding component. Rather, speech is recognized, and the recognized speech is sent to the dialog management component, which then provides the user with feedback in the form of text audio output and graphical output. This system describes the general structure of MossTalk Words, discussed in Chapter 8.

Fig. 1.2: Speech/lexical feedback components.

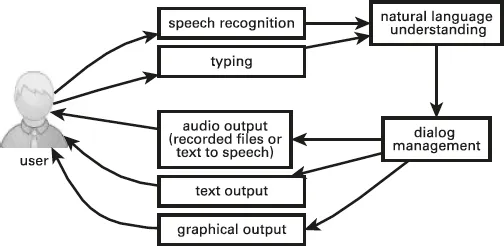

Fig. 1.3: System for language/grammar feedback.

As another example, a system designed to provide the user only with feedback on their language would look more like the system shown in Fig. 1.3. Here the user speaks or types to the system with the intention of producing a more or less complete sentence. This kind of system is focused on providing feedback to the user on their language; although speech would be an option for input, typed input is also possible with this kind of system, if that is appropriate for the application and for the users. GrammarTrainer, an application for helping users with autism improve their grammar, discussed in Chapter 3, is a system of this kind. Users interact with GrammarTrainer with typed input.

Another system with a similar organization is the Aphasia Therapy System discussed in Chapter 9, for users with aphasia, which analyzes users spoken language and provides detailed feedback on their productions.

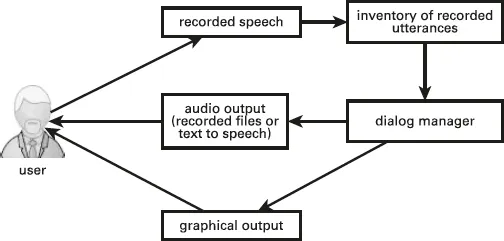

Another type of organization is shown in Fig. 1.4. This system allows the user to record short pieces of speech and assemble them into longer spoken sentences or series of sentences. An example of this type of system is SentenceShaper®, discussed in Chapter 8. The dialog manager in this case is simply the software that reacts to the user’s commands to record and play back speech at different levels.

The next few sections will discuss in more detail the individual technologies that comprise these systems. This material can be treated as background reading. It is useful in understanding the technologies that can be applied to speech and language disorders and their limitations, especially for developers, but readers can skip over the rest of this chapter if they are not interested in the details of the underlying technologies.

Fig. 1.4: System for user-initiated control and playback of user utterances.

1.2Speech recognition

1.2.1What is speech recognition?

Speech recognition is the technology that enables a computer to turn speech into written language. It is sometimes called “speech-to-text”. More technically, speech recognition is referred to as automatic speech recognition to distinguish it from human speech recognition. One way to think of a speech recognizer is as the software counterpart of a human stenographer or transcriptionist. The speech recognizer simply records the words that it hears, without attempting to understand them.

Speech recognition starts with capturing speech and converting it from sound, which is physically a sequence of rapid changes in air pressure, into an electrical signal that mirrors the sound, the waveform, through the use of a microphone. Perhaps surprisingly, the waveforms for what we perceive as a sequence of words do not include physical gaps corresponding to what we perceive as word boundaries. There are rarely silences between words in actual speech, and conversely, there can be silences in the middle of words that we do not perceive as silence. In addition, the same sounds can be spoken in many different ways, even though they sound to human listeners like the same sound. In addition to the speaker’s words, many additional factors can affect the actual physical sounds of speech. These include the speaker’s accent, the speaker’s age, how clearly the speech is articulated, how rapid it is, and whether the conversation is casual or formal. In addition, in the real world, speech will inevitably be mixed in with other sounds in the environment, such as noise, music, and speech from other people. One of the most difficult problems today in speech recognition research is separating the speech that a system is interested in from other sounds in the environment, particularly from other speech. For all of these reasons, the technologies behind the process of converting sounds to written words are very complex.

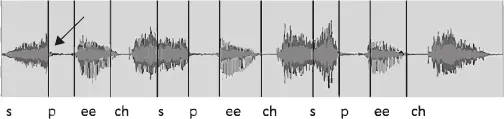

Fig. 1.5: Speech waveform for the word “speech” spoken three times.

As an example, Fig. 1.5 shows the waveform for the word “speech” spoken three times, with the sounds mapped to the parts of the waveform to which they correspond. Distance from the middle indicates the amount of energy in the signal at that point. Note that none of these look exactly the same, even though they were spoken by the same person at almost the same time. We can also see that the “ch” at the end of each “speech” merges into the “s” at the beginning of the next word without any actual silence (as indicated by a flat line in the waveform). Also note that the “p’s” and the “ch’s” each contain a brief introductory silence, pointed to by the arrow for the first “p”, that we do not hear as a silence.

The following discussion presents a very high level overview of how today’s speech recognition technology works. Speech recognition is the process of trying to match waveforms, as shown in Fig. 1.5, which are highly variable, to the sounds and words of a language. Because of the variable nature of the waveforms, the process of speech recognition is heavily statistical, relying on large amounts of previously transcribed speech, which provides examples of how sounds (the signal) match up to the words of a language. Basically, the recognizer is trying to find the best match between the signal and the words of the language, but mistakes, or misrecognitions, are very possible, particularly when the speech occurs under challenging conditions that make it harder to hear.

The next task in speech recognition is to analyze the waveform into its component frequencies. Speech, like all sounds, can be broken down into a combination of frequencies, referring to different rates of vibration in the sound. Frequencies are measured in terms of cycles per second, or hertz (Hz). We perceive lower frequencies as lower-pitched sounds and higher frequencies as higher-pitched sounds. The energy present in the signal at different frequencies is referred to as the spectrum.

The spectrum is more useful in speech recognition than the waveform because it shows more clearly the amount of energy present at different frequencies at each point in time. This energy is very diagnostic of the specific sp...