![]()

Michele Aresta, Angela Dibenedetto, and Franck Dumeignil

1 Catalysis, growth, and society

In developed countries, modern society enjoys unprecedented levels of well-being and comfort enabled by access to a variety of man-made goods in addition to natural goods, efficient medical treatments and prevention, abundance of high-quality food, rapid access to information, comfortable and rapid global travel, and “easy-to-use and transport (batteries)” energy. Chemistry underpins almost all of the technological innovations that make everyday human life as comfortable as possible, being transversal to food-health-energy-mobility-environment-housing. Ninety-five percent or more (in volume) of all the products of the chemical industry are synthesized using at least one catalytic step. Approximately 20% of the world economy depends directly or indirectly on catalysis.

However, the dependence of society on chemistry and catalysis will increase with the growth in population and the demand for higher standard and quality of life.

Catalysis has been underlined as a key enabling technology for the future by several international (e.g., the SusChem Programme) and national (USA, Japan, China, UK, the Netherlands, France, Italy, among others) organizations. Sustainability in chemistry is one of the key targets of the industry of the future, and catalysis is the basis of sustainable chemistry. Several societal programs, while often not openly including the word “catalysis”, are nevertheless built around it.

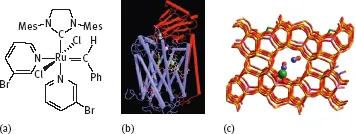

Production processes can be broadly categorized into two large families, namely (i) biotechnological transformations and (ii) chemical conversions, driven or not by catalysis. Variations of the latter are homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis if the catalyst and the reactants are dissolved in the same medium or if the catalyst is in the solid state while the reactant(s) is(are) in the gas and/ or liquid state, respectively. Biotechnological transformations can be carried out using entire microorganisms or enzymes (Figure 1.1b), soluble or heterogeneized. Chemical catalysts (Figure 1.1 a, c) can be inorganic salts, synthetic molecular edifices, metal-organic systems, or metals, metal oxides, solid composite materials, organic species, protons, and so on.

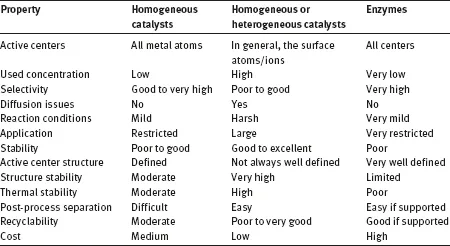

The boundaries between the above categories are becoming progressively blurred, and such technologies are often sequentially combined, or more recently, in an even more integrated one-pot approach known as “hybrid catalysis”. The different types of catalysis have their respective advantages and disadvantages, as summarized in Table 1.1.

Irrespective of the concerned catalytic species, a catalyzed process involves the faster transformation of molecules under more “facile” conditions than in the absence of a catalyst.

Fig. 1.1: epresentation of a Homogeneous catalyst (used in metathesis, a), an Enzyme (Cytochrome C Oxidase, b) and a Heterogeneous catalyst (zeolite structure, c).

Table 1.1: Comparison of catalysts.

Figure 1.2 shows the global energetic variation of a non-catalyzed (a) and a catalyzed (b) reaction. It is clear that the catalyst modifies the pattern of the energy profile. A “positive” catalyst lowers the energetic barrier that must be overcome for the chemical transformation to occur and ensures that a higher number of reagent molecules (reactant) be converted per unit of time under specific reaction conditions (temperature, pressure, solvent) than under non-catalyzed conditions.

Typically, a catalyst makes a reaction occurring in milder conditions (lower temperature) and increases the rate of the reaction, while the equilibrium position remains unaffected. Nevertheless, there are also catalysts that can hinder a reaction by increasing the activation energy (Figure 2.2c). Such “negative” catalysts are not rare in bioprocesses and also exist for chemical reactions.

Fig. 1.2: The effect of catalysts on the reaction energy profile.

While a basic treatise of catalysis will be a good guide to beginners, we briefly summarize hereafter some basic concepts that may be useful when reading this volume.

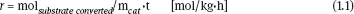

The properties of a catalyst are expressed in different ways such as activity, conversion of reagents, selectivity, stability, turnover number (TON), and turnover frequency (TOF). The activity of a catalyst can be represented by the reaction rate expressed as

Alternatively, the volume of catalyst can be used, and the expression of the rate becomes

The kinetic activities are experimental values.

where k is the kinetic constant and depends on the Arrhenius equation:

The equations above suggest that the activity of a catalyst can be expressed in three different ways: through the rate of a reaction, the rate constant of the reaction, or the activation energy, Ea. The comparison of catalysts can be correctly done using the rate at zero-time, ro.

Conversion gives the fraction of the jth reagent (percentage or molar fraction) converted. Selectivity represents the fraction of jth reagent converted into a target product. The stability of a catalyst is a measure of its life expressed in units of time (h, d, y). Sometimes, deactivation rate is expressed, which is the parameter that gives information on the loss of activity of the catalyst during a given time.

TOF gives the number of units (or moles) of jth reagent converted per mole of catalyst in the unit of time (s, h). It is expressed in units of reciprocal time (t-1). TON gives the number of substrate units (moles) converted per catalytic center until it becomes inactive. TON is easily defined for enzymes and for homogeneous catalysts, but it is much lesser for heterogeneous catalysts, because, often, it is not straightforward to identify the number of active sites.

Catalytic processes that use heterogeneous catalysts can be carried out in batch or in flow reactors (see specialized books for their properties). For a flow reactor, the space velocity of the catalyst is defined as the ratio of the specific volume in flow (V/t) per unit mass (or volume) of the catalyst.

In the above equation, if the mass of catalyst m is substituted by its volume V, the SR becomes equal to the reciprocal of the residence time (SR = t-1). Another quantity often used to characterize the solid catalysts is the space-time yield (STY) for the jspecies given by

where molj represents the number of moles of the jth species and Vcat.is the volume of catalyst.

In the case of biochemical (or biotechnological) processes, the catalysts are enzymes, which are characterized by the following properties:

Inserted –They are all proteins with complex structures and an active center with a welldefined geometry.

–They are either pure organic species or contain a metal (metal-enzymes) as the active site.

–The way enzymes work is affected by the temperature, pH, solvent, and pressure. They can be denatured (unfolded or destroyed) by excessive heat and other factors.

–All reactions are reversible.

–Enzymes are very specific, that is, they control only one reaction or convert a welldefined substrate into a specific product.

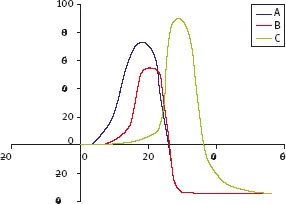

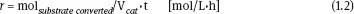

Fig. 1.3: Correlation of the reaction rate v to the substrate concentration [S] in an enzymatic reaction.

The mechanism of enzymatic reactions has long been studied by analyzing the composition of enzymes and their structures. Leonor Michaelis and Maud Menten proposed a method for describing enzyme kinetics based on experimental facts.

In an enzymatic reaction, the initial reaction rate v is increased by increasing the concentration [S] of the substrate S. However, in cases where the amount of enzyme added to the reaction system is fixed, no matter how much [S] is increased, v cannot increase over a certain limit (Figure 1.3). Such extrapolated value is called vmax, which means that v is saturated with regard to [S].

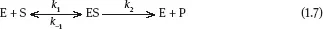

The phenomenon of saturation is characteristic of catalytic reactions and is explained as the binding of a substrate to a catalyst. The phenomenon of saturation is observed because even if there is an abundance of substrate molecules, the number of substrate binding sites available over the catalyst is limited. For a generic and simple enzymatic reaction such as Eq. (1.7),

a general equation has been established, known under the “Michaelis-Menten equation”:

with

Here, vmax refers to the maximum initial reaction rate and km is the Michaelis-Menten constant. It represents the value of [S] for which the initial reaction rate is equal to ½ vmax.

However, this equation is essentially a hyperbolic function demonstrating the phenomenon of saturati...