![]()

Part I: Introduction

![]()

1The central problems

1.1The story to be told

Herbert Frahm was born in Lübeck in 1913. Since Herbert Frahm was active as a socialist, he escaped Germany in 1933. When he was in exile, he adopted the pseudonym “Willy Brandt”; subsequently, he became the first socialist chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany. Based on these historical facts, let us suppose that he had a former neighbor named Betty. Further, suppose that there was another person, Rudolf, whom Betty met one day in the 1950s:

Rudolf: Do you know Willy Brandt?

Betty: Yes, he is the mayor of Berlin. He is from Lübeck.

Rudolf: How about Herbert Frahm? Do you know him?

Betty: He was my former neighbor, but he came from Berlin.

After this conversation, Rudolf attributed a belief to Betty. Namely, she believes that Willy Brandt was born in Lübeck, but Herbert Frahm was not.

Some time later, Rudolf told Lucy his belief ascription in the following manner, because Rudolf knew that Herbert Frahm was the same person as Willy Brandt and that Lucy did not know who Herbert Frahm was:

Rudolf: Betty was a former neighbor of Willy Brandt, and she believes that Willy Brandt was born in Lübeck but Herbert Frahm was not.

In the following discussion, I will take the following sentences as representing Rudolf’s reports:

(1)Betty believes that Willy Brandt was born in Lübeck.

(2)Betty believes that Herbert Frahm was born in Berlin.

These are the belief reports that are analyzed in this book. Using the following two sections, I will characterize the focus more accurately.

1.2Propositional attitudes and their attributions

This book analyzes belief reports, for example, Rudolf’s assertions of (1) and (2). Now, I briefly sketch the type of beliefs that are reported. Generally, beliefs are a type of propositional attitudes. Epistemic subjects, like Betty, have attitudes such as fear, hope, desire, and so on. They are directed towards the state of affairs. Among them, there is a class of attitudes that are characterized in terms of linguistic propositional contents (propositional attitudes); for example, desires, beliefs, and thoughts belong to this class. They are of philosophical interest because they constitute the reason for intentional actions (Anscombe 1979; Davidson 1963). Beliefs and desires are reasons for intentional actions in the sense that there is a practical inference that takes certain desires and beliefs as the premise and draws an action as consequence.

There are two ways of approaching one’s beliefs. One is from the perspective of the epistemic subject who actually has an attitude toward linguistic content. The other is from the perspective of an observer who ascribes such an attitude to a subject. In the following discussion, I focus on the latter. Furthermore, I restrict my discussions to belief ascriptions to a third person, and ignore self-ascriptions. Beliefs are ascribed to some subjects as having a positive stance toward some facts or states of affairs. For example, Rudolf ascribed a belief to Betty when he observed that Betty assents to (3):

(3)Willy Brandt was born in Lübeck.

This observation is made typically by hearing her assertion of (3). There are two types of audience. One is the addressee, Lucy, to whom Rudolf intends to report his belief ascription. The other is the silent listener who is not Rudolf’s intended audience.

1.3Type of attitude reports concerned

If a person attributes beliefs to someone, she can report this to another person. These reports are the main objectives in the following discussions. I call the reports of this specific type of propositional attitude ascriptions “belief reports.” Belief reports are stated in English spoken language,1 typically by using verbs, for example, “believes” and “thinks”; the following are a few examples of this:

(1)Betty believes that Willy Brandt was born in Lübeck.

Linguistically, belief reports are a type of indirect speech report or indirect quotations. The characterization of indirect (as well as direct) speech reports are provided in chapter 3.

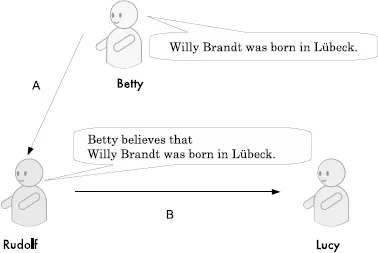

For now, it suffices to note the following: First, there are three parties involved in explaining the meaning of a belief report, namely believers, reporters, and their audience. As I discuss in chapter5, it is essential for accounting the meaning of a belief report that the believer and the audience do not normally share the same context (see figure 1.1). Second, a belief report is an assertive utterance of a reporter such that its content is truth-evaluable. It is our working hypothesis that what a belief report means to the audience is merely its truth-evaluable content. Third, a standard belief sentence, with which a belief is reported, comprises two subsentential constituents. For each subsentential constituent, I introduce a terminology pair of the inset and the frame (Sternberg 1982,108).

(1)Betty believes that WILLY BRANDT WAS BORN IN LÜBECK.

In this example, the inset (marked with SMALL CAPS) is the content clause in English belief reports. The frame is the rest of the sentence. This terminology pair is needed because they enable us to discuss various forms of belief reports in a uniform manner.2 Finally, and most importantly, a reporter of a belief does not have to commit himself/herself to the content expressed in the inset of a belief sentence so that he/she can ascribe some false beliefs to the believer in question.

This feature appears self-evident, but the question is how to implement this to a theoretical account of natural language meaning.

1.4Opacity and contents of belief reports

Although belief reports are commonly used in our linguistic practice, they are not easy to analyze semantically. Since a belief report is an assertion, its semantic content is normally true or false. However, to determine the content of a belief report, it is a perplexing fact that the substitution of coreferring singular terms, particularly proper names,3 affects the truth-values of belief reports (for example, Frege 1892). To see the point, take the following example: Suppose Betty attached different modes of presentation to “Willy Brandt” and “Herbert Frahm” despite the fact that they are actually coreferential proper names. Due to different modes of presentation, she would accept (3) but deny (4):

(3)Willy Brandt was born in Lübeck.

(4)Herbert Frahm was born in Lübeck.

Despite Betty’s different reactions, both sentences have the same truth-value, and “Willy Brandt” and “Herbert Frahm” can be substituted without changing the truth-value of the sentence. However, when Rudolf reported Betty’s reactions in the following manner, the substitution of one name with the other might have changed the truth-value of the following reports:

(1)Betty believes that Willy Brandt was born in Lübeck.

(5)Betty believes that Herbert Frahm was born in Lübeck.

That is, a proper name, such as “Herbert Frahm,” seems to occur opaquely in the inset of a belief report.

Definition 1 (Working definition of opacity). For every report r, there is a proper name n that occurs opaquely in r if and only if there is another proper name that is coreferential with n, and substituting these proper names can affect the truth-value of r. Otherwise, n occurs transparently.

The opaque occurrence of a singular term in an inset poses a question concerning the semantic content of a proper name. In objective theory of meaning, there are two relevant theses here: genuine referential nature of proper names and compositionality. First, a proper name is a singular term that is used as genuinely referential. That is, the semantic value of a proper name, for example, “Herbert Frahm”, is nothing but the referent, namely, Herbert Frahm himself in this example. If we observe this thesis more precisely, it actually includes two further claims: a proper name refers to its referent, and the referent is a semantic value. Furthermore, if a proper name is used genuinely referentially, the referent is the only semantic value of the proper name. This latter thesis is called semantic innoce...