- 455 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Mathematical Stereochemistry

About this book

Mathematical Stereochemistry uses both chemistry and mathematics to present a challenge towards the current theoretical foundations of modern stereochemistry, that up to now suffered from the lack of mathematical formulations and minimal compability with chemoinformatics.

The author develops novel interdisciplinary approaches to group theory (Fujita's unit-subduced-cycle-index, USCI) and his proligand method before focussing on stereoisograms as a main theme. The concept of RS-stereoisomers functions as a rational theoretical foundation for remedying conceptual faults and misleading terminology caused by conventional application of the theories of van't Hoff and Le Bel.

This book indicates that classic descriptions on organic and stereochemistry in textbooks should be thoroughly revised in conceptionally deeper levels. The proposed intermediate concept causes a paradigm shift leading to the reconstruction of modern stereochemistry on the basis of mathematical formulations.

•Provides a new theoretical framework for the reorganization of mathematical stereochemistry.

•Covers point-groups and permutation symmetry and exemplifies the concepts using organic molecules and inorganic complexes.

•Theoretical foundations of modern stereochemistry for chemistry students and researchers, as well as mathematicians interested in chemical application of mathematics.

Shinsaku Fujita has been Professor of Information Chemistry and Materials Technology at the Kyoto Institute of Technology from 1997-2007; before starting the Shonan Institute of Chemoinformatics and Mathematical Chemistry as a private laboratory.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Table of contents

- Cover

- Titel

- Copyright

- Preface

- About the author

- Contents

- 1. Introduction

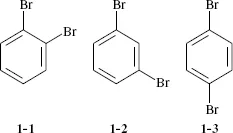

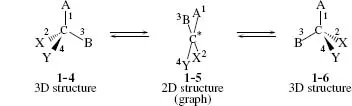

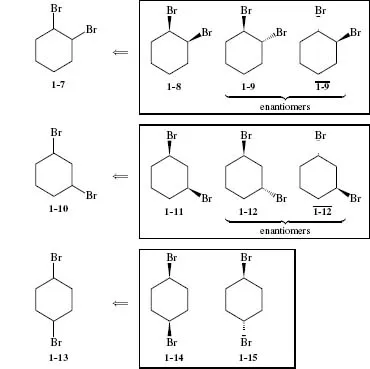

- 2. Classification of Isomers

- 3. Point-Group Symmetry

- 4. Sphericities of Orbits and Prochirality

- 5. Foundations of Enumeration Under Point Groups

- 6. Symmetry-Itemized Enumeration Under Point Groups

- 7. Gross Enumeration Under Point Groups

- 8. Enumeration of Alkanes as 3D Structures

- 9. Permutation-Group Symmetry

- 10. Stereoisograms and RS-Stereoisomers

- 11. Stereoisograms for Tetrahedral Derivatives

- 12. Stereoisograms for Allene Derivatives

- 13. Stereochemical Nomenclature

- 14. Pro-RS-Stereogenicity Based on Orbits

- 15. Perspectives

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app