eBook - ePub

Change of Paradigms – New Paradoxes

Recontextualizing Language and Linguistics

- 397 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Change of Paradigms – New Paradoxes

Recontextualizing Language and Linguistics

About this book

In Paradigm and Paradox, Dirk Geeraerts formulated many of the basic tenets that were to form what Cognitive Linguistics is today. Change of Paradigms –New Paradoxes links back to this seminal work, exploring which of the original theories and ideas still stand strong, which new questions have arisen and which ensuing new paradoxes need to be addressed. It thus reveals how Cognitive Linguistics has developed and diversified over the past decades.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Change of Paradigms – New Paradoxes by Jocelyne Daems, Eline Zenner, Kris Heylen, Dirk Speelman, Hubert Cuyckens, Jocelyne Daems,Eline Zenner,Kris Heylen,Dirk Speelman,Hubert Cuyckens in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Filología & Lingüística. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One: Language in the context of cognition

Instru-mentality

The embodied dialectics of instrument and mind

Abstract: Both tools and instruments are artifacts with a cognitive bend. That means that in using them, we both exercise our cognitive faculties to improve our environment, and in return, improve our faculties by adjusting to the input we register as cognitive feedback. As a result, not only do cognitive artifacts change the tasks we perform; it is equally true that the use of such artifacts changes our minds. The resulting “instru-mentality” is characterized by its increased/diminished distance to the artifacts, with the corresponding cognitive feedback moving in the opposite direction. Some implications relating to psychological issues and the use of prostheses in restorative and recuperative medicine are discussed; here the important notion of “adaptability” is given some prominence.

For Dirk, on his coming of “age”: a personal introduction

Having met Dirk several times at conferences (but limiting ourselves to mostly agreed-on commonsensical exchange), our first real mental encounter hap-pened, ironically, through the medium of an instrument: written, even printed, text.

I had been asked to review Dirk’s 2010 book Theories of Lexical Semantics; this turned out to be much more than a superficially satisfying task, as it allowed me for the first time to take proper measure of Dirk’s profile and size as a researcher and independent linguistic thinker. The review (Mey 2011) became quite lengthy, but I managed to get it accepted without too many cuts; next, having accomplished the technical part of my task, I asked myself what had most impressed me during the process of reviewing. The answer: Dirk’s ability to combine insights, clarity, erudition, and communicative skills — a characteristic that proves to be fitting also for his other works.

Dirk’s oeuvre stands out as the perfect instrument for transmitting superb mental content; which is after all what “instru-mentality” is all about. Hence the title of my contribution, which is hereby humbly offered to the young sexagenarian with the age-seasoned wish of Ad multos annos (to which I add: atque opera!).

Austin, TX, 3 March 2015

Jacob L. Mey

Jacob L. Mey

1 Introduction: On instru-mentality and “toolness”

In our everyday use of language, we make a distinction between the terms “tool” and “instrument”. Instruments are tools, but not all tools are instru-ments; though closely related, the terms don’t seem to be synonymous. Thus, we talk about instruments for making music; we have surgical instruments; we are familiar with the instruments on the dashboard of a car or in the cockpit of a plane, but would never think of calling them “tools”. In contrast, we talk of a tool box, a carpenter’s tools, bicycle tools, gardening tools, and so on; we would minimally lift an eyebrow, should someone start to refer to these tools as “in-struments”. Clearly, we are making a distinction, but upon what basis? And: could an examination of the distinction lead to insights into the ways humans construct and orchestrate cognitive interactions and events? Is instrumentality itself a matter of cognitive social adaptation? The present paper explores this possibility.

One clear (but perhaps a bit superficial) way of differentiating between tools and instruments comes to light when we compare their representation and physical presence in a car: the instruments are found on the dashboard, close at hand, while the tools are in the trunk, to be brought out only for special reasons (such as fixing a flat, or recharging the battery). However, the distinction is not simply a matter of location and relative importance of function (for example, is a cigarette lighter, following this distinction, an instrument, a tool, or simply a gadget?) Still, the example is useful in that it makes us realize that the various objects we purposefully use are, in some critical sense, distinguished and constructed socially. As a case in point, take the common tool known as a hammer. As such, it is just a piece of ironware; but in a Marxian inspired line of thinking, it becomes a tool by (and only by) entering the social production process, by being “socialized”. This socialization is critical to the determination of its status. In the final resort, the determination is a cognitive process, governed by human user need and user skill, not by the object itself as a physical entity. Consider, for instance, that the same hammer tool that you used for fixing a picture to your living room wall, may be cognitively and manually repurposed by a physician in need of an instrument to test your knee reflexes.

2 On artifacts, both cognitive and others

Generalizing, then, it seems safe to say that both tools and instruments are social artifacts with a cognitive bend. The notion of “artifact” was originally coined in archaeology and physical anthropology. It is used to indicate the presence of a human agent as embodied in a piece of nature, for example a fetish or a primitive tool. If I find such an “artificial” object in nature, my first thought is that somebody out there made it, or put it there. Moreover, by further extending the critical importance of human agency in shaping the artifact, we may consider the very act of finding as transforming the object into an artifact. Thus, the mere fact of having been found by a human agent such as an artist transforms a piece of nature into an objet trouvé, the odd item (possibly itself an artifact) that cognitively embodies the artist’s conception, as expressed in what we now consider to be a “work of art”, complete with signature and date, and liable to be collected, exhibited, traded, and occasionally even vandalized or stolen.

Cognitive artifacts, as the name suggests, are of a special kind, being related to the ways humans cognizingly deal with, and represent, the world and how they use those representations; in other words, they are cognitive tools. The common artifact known as the book provides a good example; compare the following early comment by Donald Norman:

Cognitive artifacts are tools, cognitive tools. But how they interact with the mind and what results they deliver depends upon how they are used. A book is a cognitive tool only for those who know how to read, but even then, what kind of tool it is depends upon how the reader employs it (Norman 1993: 47).

Considering “toolness” as dependent on cognition (as in the case of the book) implies that we somehow are able to use the artifact in our cognitive operations. At the low end of toolness, we find devices such as the cairn or other simple stone artifacts, some possibly used to mark distances or time periods; an outlay of twigs or arrows may point the way to food; the primitive flintknapper’s tool betrays the presence of early humans’ ways of dealing with the environment. In the case of the book, the feedback that various kinds of people get from reading may be quite different, depending on their world orientation and their cognitive and other abilities. Babies use books mostly to tear them apart. Older children look at pictures. Adults (and proficient younger readers) spurn the pictures and go directly to the text itself. Mature readers take in all these “bookish” aspects and synthesize them into a single, smooth, well-adapted cognitive behavior.

3 Representation and embodiment

The importance of cognitive artifacts resides in the fact that they represent the world to us. In his classical tripartition, Charles S. Peirce distinguished between three ways of representing: by indexes (e.g. the arrow pointing to some location), by icons (a cognitive artifact bearing a certain resemblance to the object represented, such as the universal pictogram for “No Smoking”, a slashed or crushed cigarette), and by symbols (such as our words, that represent objects and thoughts via (re)cognitive operations that are not premised on any particular physical shapes).

But representation is not just a state: it involves a process, a representing activity. Humans are representing animals; but in addition, they cognitively embody “surplus” meanings in the objects and activities they represent — a meaning that is often far removed from the object or activity itself and its simple representation. For instance, walking, considered as pure locomotion, has no meaning other than that embodied in the move itself from point A to point B. However, when it comes to vote-taking in the Roman Senate, a Senator gathering up his purple-lined toga and walking from the one end of the Senate Chamber to the other side in order to take his place among his like-minded colleagues, performs an official act of voting, aptly called “letting one’s walk express support” for what we today would call, equally aptly though somewhat anachronistically, a “motion”. (In Roman times, such embodied cognitive action was called pedibus ire in sententiam, literally ‘having one’s feet do the voting’). Here, the simple movement of walking embodies a mental representation: in true “instru-mentality”, the cognitive motion is seconded and approved by the Senator’s embodying feet.

4 Cognitive artifacts and their representations

How do artifacts represent meaning and action? As Norman has pointed out, “to understand cognitive artifacts, we must begin with an understanding of representation” (1993: 49). But even the best representation only comes alive on the condition that we have a human who actively interprets what is represented. In other words, the artifact must not only offer a complete (or at least passable) representation, but it must also represent in such a way that the people using the artifact will have no trouble identifying what is represented and how the representation works.

Moreover, whenever a cognitive artifact represents, its way of representing must be adapted to, and be adaptable by, both the represented and the interpreter. The adaptation, however, should not be seen as a quality given “once and for all”: adaptation is a process of give and take, of mutual conditioning; in short, it is a dialectical communicative process.

In order to situate that mutual interaction, I suggest the following three propositions:

(1) All artifacts, when viewed through the lens of instru-mentality, are in some measure cognitive artifacts;

(2) Even the mind itself, as the instru-mental version of the brain, is a cognitive and goal-driven artifact, inasmuch as the brain develops as a mental instrument for interacting with the environmental context through the organization and integration of perceptual data;

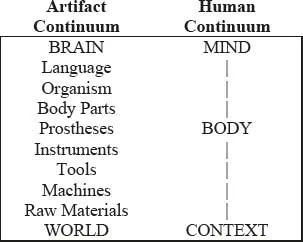

(3) All artifacts can be situated on a continuum of adaptation between, on the one hand, the extremes of the world’s raw materials and the brain, and on the other, the endpoints formed by the environmental context and the mind (see Figure 1)1.

The computer is of course the cognitive artifact par excellence; but more generally, what do we mean when we talk about an “instrument of mind”? What is implied in the term “instru-mentality”? The next section will provide an answer to this question.

Fig. 1: Relationship between a continuum of artifacts and the continuum between a perceiving human and the environmental context

5 The dialectics of instru-mentality

Donald Norman has remarked that “artifacts change the tasks we do” (1993: 78); however, it is equally true that the use of artifacts changes our minds. Through instru-mentality, the very tasks we perform no longer seem to be the same tasks as before; in addition, instru -mentality has us consider ourselves as changed in relation to the tasks. Thus, a housewife owning a vacuum cleaner is changed by the very fact of her user/ownership: a simple artifact, a household gadget that was supposed to relieve the chores of countless women, turned out to be a mighty household tyrant, raising the bar for housework that had been standard earlier. Similarly, the mechanization of household waste removal, by transforming the simple collection and emptying of old-fashioned garbage bins on to open flatbed trucks, into the single-user operation of hightech sanitation vehicles that will do everything needed in a single mechanical operation, has not only changed the status of the process and the artifacts involved, but in addition has redefined the task itself and its incumbents. This new instru-mentality comes to light in the new names that were assigned to the artifacts and their “interpreters”: when garbage pick-up became “sanitation”, the workers were re-branded as “sanitation engineers”, who (as a result of this mini-revolution in a complex of menial urban tasks) had to work harder in order to stay profitable.

6 Feedback and distance

There is always some reflexive acti...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Content

- Eline Zenner, Gitte Kristiansen, Laura Janda, and Arie Verhagen? Introduction. Change of paradigms - New paradoxes?

- Part One: Language in the context of cognition?

- Part Two: Usage-based lexical semantics and semantic change

- Part Three: Recontextualizing grammar?

- Part Four: The importance of socio-cultural context

- Part Five: Methodological challenges of contextual parameters?

- Index

- Endnotes