![]()

1Introduction and overview

1.1Historic, ancient

Metals have shaped human societies and human history since before recorded history. Many societies pass through what is called a Bronze Age before entering an Iron Age, a phenomenon identified by the melting points of a metal alloy and an elemental metal, respectively. The fact that the melting point of iron is significantly higher than the melting points of bronze alloys means that iron ages occur after bronze ages, as the ability to make higher temperature fires was achieved in a particular civilization.

Several ancient societies have made extensive use of different elemental metals or alloys, and are still noted for them today. For example, Han Dynasty bronze urns and other objects reached such an apex of the metallurgist’s art that these ancient bronzes continue to command high prices in the auction houses of the world’s art market today. In ancient Egypt, some of the earliest iron that was worked came from meteorites, and was made into knives that were rather romantically called ‘daggers from heaven’ by their users. As well, the rise of Rome from a republic to an empire corresponded with the expanded smelting of iron and its widespread use in weaponry and tools within its territories, so much so that pollution from it has been recovered from the Greenland ice cap. Other civilizations and their advances are also marked by the increased use of bronze and iron.

Some civilizations have used metals extensively, but have not specifically gone through bronze and iron ages. Several of the pre-Columbian societies of Central and South America, for example, were skilled at the use of gold, but never appear to have worked iron. Gold objects from the Aztec, the Inca, the Moche, the Chimu, and peoples who inhabited the Amazon Basin at the time of European first contact were noted by European chroniclers in their journals and memoirs [1].

1.2Large-scale use

Prior to the Industrial Revolution, the production of metals was conducted on a relatively small scale, utilizing a great deal of human labor at each step of the production and refining process. While such processes rose to what can be considered larger than cottage industries, metal working on an industrial scale only became feasible when machinery and heating apparatuses were developed that could extend the range of human abilities beyond what could be done by a single individual with an anvil, forge, and wood-, dung-, or even coal-fed fire.

Britain was an early producer of iron on a large scale as the Industrial Revolution started, in large part because the country also had abundant supplies of coal, which was needed to produce hot enough furnaces to smelt and reduce the iron. In similar manner, the Falun mine in Sweden has produced copper for over a millennium, and its production peaked during the onset of the Industrial Revolution.

For almost all productions of metals from their ores, people have had to mine the raw metal or the ore. This has led to the creation of several national or international mining organizations that advocate for the industry and its products [2–7].

1.3Eighteenth and nineteenth century discoveries

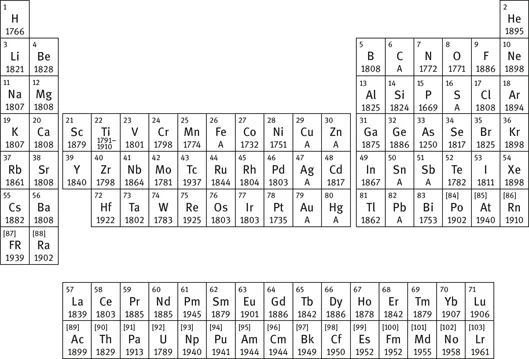

An examination of the periodic table indicates that many of the metal elements were only discovered in the past 250 years. Figure 1.1 shows a periodic table with the generally accepted year of discovery and isolation of each element listed in it. The letter ‘A’ indicates an element that was known from ancient times [8].

It can be seen that several metals and a few nonmetals were indeed known to the ancients, but the largest number of elements that we now consider industrially important were discovered between 1700 and 1900.

The discovery of numerous elemental metals in the nineteenth century did not always coincide with an immediate need or use for them, however. For example, neodymium was first discovered in 1885. However, the neodymium–iron–boron magnets (Nd2Fe14B) that have become ubiquitous in numerous applications where small, strong, permanent magnets are required, have only moved into large-scale production in the past two decades, and indeed were only first produced by General Motors in 1982. Likewise, scandium was first discovered in 1879, and while today there are several niche uses for it, sources estimate that no more than 10–15 tons are used annually [9].

1.4Modern, niche uses

Several metals and alloys exist that are important in some way, but that are still produced on a relatively small scale. For example, beryllium is only produced by three countries, and in relatively small quantities (tons, instead of tens of tons or thousands of tons), but has become extremely useful in what are referred to as X-ray windows because of its transparency to X-rays. Likewise, metals such as the just-mentioned scandium, as well as technetium and rhenium are all produced on a small scale, but all find uses in some niche in one or more specific industries. More recently, tiny amounts of americium have found use in most residences in the developed world.

Fig. 1.1: Periodic table with year of discovery of the elements.

1.5Modern, major use metals

Iron, copper, aluminum, silver, gold, lead, tin, zinc, nickel and tungsten are all metals that find enormous uses in our modern world. Some of these, such as iron, have been used since ancient times, but now fill much larger roles, such as the construction of bridges and the reinforcing structures of high-rise buildings. Likewise, copper has been used for millennia, but only in the past two centuries has it been utilized in the tens of thousands of miles of wiring that delivers electricity to homes, businesses, and other concerns of the modern world.

Unlike iron and copper, aluminum has gone from discovery in 1825 to use in thousands of applications today. In this case, the production of inexpensive electricity was the key to making large-scale refining of aluminum an economically feasible idea. Similarly, tungsten has a relatively short history, but has found widespread use in a variety of alloys today.

1.6Recycling and re-use

In almost every case, it is economically beneficial to recycle refined metals when one compares the cost to that of refining new metals from ores. Indeed, some metal recycling has gone on for a century, with metal drives being a part of national economies in both world wars. Today, developed nations throughout the world often mandate some form of metal recycling – often of various food and beverage cans – although different states and provinces in different countries may not have the same requirements and standards. Also, some metals are used in such small amounts in end-user products that there are not yet recycling programs for them. The relatively new recycling of cell phones may be an attempt to remedy that situation when it comes to neodymium, for example.

This book will discuss recycling when possible, from metals that are produced on enormous scales, to metals that are produced in small amounts, but that serve some vital niche use.

Bibliography

[1]The Discovery Of The Amazon: According To The Account Of Friar Gaspar De Carvajal And Other Documents (American Geographical Society), 2007, ISBN: 978-1432557195.

[2]International Council on Mining and Metals. Website. (Accessed 13 April 2015, as: http://www.icmm.com/).

[3]Mining Association of Canada. Website. (Accessed 15 April 2015, as: http://mining.ca/).

[4]Australian Mines and Metals Association. Website. (Accessed 15 April 2015, as: http://www.amma.org.au/).

[5]European Association of Mining Industries, Metal Ores and IndustrialMinerals. Website. (Accessed 15 April 2015, as: http://www.euromines.org/).

[6]National Mining Association. Website. (Accessed 15 April 2015, as: http://www.nma.org/).

[7]40 Common Minerals and Their Uses. Website. (Accessed 15 April 2015, as: http://www.nma.org/index.php/minerals-publications/40-common-minerals-and-their-uses#).

[8]International Women In Mining Community. Website. (Accessed 16 April 2015, as: http://womeninmining.net/library/associations-by-mineral-metal/).

[9]United States Geological Survey. Mineral Commodity Summaries, 2015. Website. (Accessed 24 June 2015, as http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/mcs/2015/mcs2015.pdf).

![]()

2Copper

2.1Introduction

Copper and its alloys have an ancient history in many cultures. The island of Cyprus gives its name to the metal because so much was used in ancient Greece and Middle East, bu...