Topological and visual analyses in the space syntax tradition on the one hand and GIS-based spatial analyses on the other have started out on very different trajectories, not only in the scope of applications but also in their underlying premises; the Euclidian metric basis of the latter, for instance, stands in stark contrast to the idea of a configurational topology which forms the basis of traditional space syntax. More recently, there has been a notable convergence both in analytical scope and in the form of software implementations; this has not been paralleled, however, by comparable efforts in terms of explicitly comparative or even integrative studies, a gap we seek to (begin to) address in the present paper on the basis of parallel analyses of topological, visual and metric properties for two case studies. The purpose of this exercise is threefold: Firstly, comparisons of the respective analytical results will aid an appreciation of the strengths and potential weaknesses of specific approaches as well as an identification of both complementary and alternative techniques, but will ultimately also help to gain a reliable basis for future integrative work. Secondly, and more specifically, GIS-based metric integration analysis will be introduced and ‘field-tested’ in comparison with conventional space syntax analyses, from which it derives – in a first step towards a more integrated perspective – part of its inspiration. Thirdly and no less importantly, we seek to contribute to a better understanding of the archaeological contexts under discussion, i.e. the Middle Bronze Age Building A of Quartier Mu at Malia on Crete and the Late Bronze Age palace of Pylos at Ano Englianos in Messenia.

1 Introduction

Analysis of topological, visual and metric properties of spatial settings has seen numerous applications in archaeology in recent years, particularly in the form of space syntax analysis and GIS-based techniques since the 1980s and 1990s respectively. Despite their common interest in the spatiality of past human life and the search for a multi-faceted, empirical framework for studying this particular domain, space syntax and GIS techniques in archaeology long constituted distinct fields of research.

This could be seen to be due, in part, to the disciplinary history of both approaches outside archaeology. One of the most notable differences in this regard lies in the fact that GIS was conceived as a technology more than anything else, coming into existence without any particular theoretical basis and thus not depending on any specific epistemology –its positivist branding today is largely explicable through its eventual adoption by spatial-analytical geography in the 1970s and 1980s (Pickles 1995; Schuurman 2000; Kwan 2004; Harvey et al. 2005; Sheppard 2005; Leszczynski 2009; Hacıgüzeller 2012a; 2012b; cf. Wheatley, this volume) –, whereas the main advocates of space syntax have proposed and continue to advocate it as an encompassing theoretical framework (e.g. Hillier 1999, p. 165; 2008). However, the latter position has found little support in archaeology and related disciplines such as social anthropology, where such theoretical aspirations have been mostly either ignored in favour of a ‘toolbox’ approach – which as with GIS allows for the methodology’s use in different theoretical frameworks – or even severely criticized (cf. Leach 1978; Batty 2004, p. 3; Thaler 2005, p. 324; Dafinger 2010, p. 125–127, 134–140). In acknowledgment of this previous reception, but also in order to facilitate an integrative discussion together with other approaches (cf. Thaler 2006, p. 93–100; Dafinger 2010, esp. p. 137), space syntax will be consciously taken as a methodology ‘only’ in this paper.

It would appear, given this common methodological stance, that the reasons for the separateness of space syntax and GIS-based studies in archaeological practice may more plausibly be identified in both technical issues, i.e. in particular the software employed in analysis, and differences of resolution, i.e. the scale of contexts commonly studied through either set of techniques. It deserves particular attention, therefore, that it is precisely in these two respects that a remarkable convergence can be noted in recent years: archaeological GIS, for example, is to some degree experiencing a ‘scaling down’, which in terms of resolution brings it closer to the traditional remit of space syntax studies. While the landscape level is still most commonly focused upon (Wheatley 2004; cf. Wheatley and Gillings 2002; Conolly and Lake 2006), there have been a small number of promising applications on the architectural scale as well. Cost-distance (Hacıgüzeller 2008) and 3D visual analysis (Paliou 2008; Paliou et al. 2011) at the building level have demonstrated how current GIS technology permits a study of phenomenological and cognitive properties of buildings through a detailed study of their configurational properties. In terms of software applications, space syntax techniques have been incorporated as add-ons within a GIS environment in several instances, and GIS has also served as a digital cartographic platform in which to import space syntax results (cf., e.g., Turner 2007a). Perhaps most important of all is that recent versions of Depthmap as the software mainstay of current space syntax work have come to include GIS-like features; it is now possible to enter non-spatial data in the database tables provided by the software and, much as in any GIS software, these database tables are linked to the spatial features represented (Turner 2007b).

All these trends mean that archaeologists studying ancient built environments have an increasing number of analytical approaches and – potentially complementary or possibly alternative – techniques at their disposal, often at the push of a button. What is therefore needed at this point is a sound body of comparative research in which different techniques are applied to specific test cases. To contribute to such a body of research is the main aim of this paper, and for this purpose, the analyses for each of the case studies will be followed by separate discussions on interpretative archaeological aspects and the comparison of analytical results from different approaches.

A further and related aim is to view the performance and results of an innovative GIS-BASED technique of metric analysis, which is first introduced in this study (for a related approach cf. Hacıgüzeller 2008), against the results of ‘tried-and-tested’ topological and visual space syntax analysis, which follow a deliberately conservative line (cf. Thaler 2005, p. 326), in order to better appreciate the potential as well as potential problems of the new approach. The latter differs from metric analysis conducted within a space syntax framework, as will be explained in more detail in the methodology section, in being raster-based and, concomitantly, allowing the researcher to take into consideration differences of elevation in architectural systems, as represented by, for example, stairs or ramps. Thanks to the spatio-statistical, data management and cartographic tools provided by GIS software, this technique also allows the manipulation of metric configurational results in a statistically and visually informed manner (cf. Gil et al. 2007, p. 16).

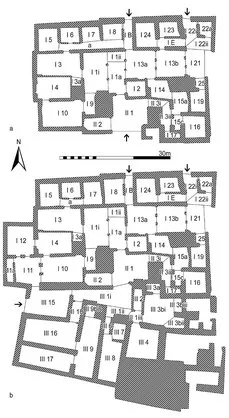

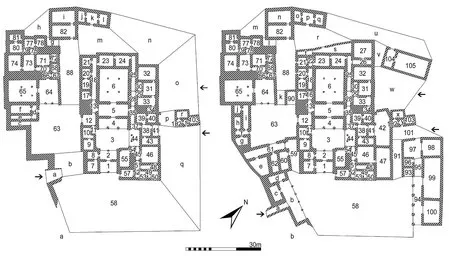

As a final point, which brings us back to the distinction between archaeological interpretations and methodological comparisons, we also hope to offer a meaningful contribution to a better archaeological understanding of the buildings which form our case studies, Building A of Middle Bronze Age Malia on Crete (fig. 1) and the Late Bronze Age palace of Pylos at Ano Englianos in Messenia (fig. 2), as well as the social phenomena they bear silent witness to. If not for that hope … why bother?

2 Methodology

2.1 Topological properties

The topological analysis here presented follows a mostly conservative space syntax methodology. Space syntax has been applied in numerous archaeological studies (cf. Cutting 2003, p. 5–7; Thaler 2005, p. 324–326) ever since its first systematic formulation in the mid-1980s (Hillier and Hanson 1984), but still retains a certain ‘exoticism’ in the field. Bill Hillier’s (this volume) introductory article sets out the basics of the methodology as well as a number of central concepts. Several of these will be employed in this paper, such as integration as a normalized measure and the most commonly used spatial indicator of topological properties, the notion of global and local qualities and effects, the distinction between the convex and the axial break-up of a building as the basis for parallel analyses, the differentiation between a-, b-, c- and d-type spaces and the mapping of integration cores, with the reader being referred to Hillier’s paper for an introduction. Some specifics as well as some additional concepts and a few points of departure, however, necessitate brief comment:

Figure 1 | Malia, Quartier Mu, Building A: a) plan of phase 1 with room numbers, points of access indicated by arrows; b) plan of phase 2 with room numbers, points of access indicated by arrows.

Figure 2 | Pylos, palace: a) plan of earlier building state with room numbers, points of access indicated by arrows; b) plan of later building state with room numbers, points of access indicated by arrows.

In purely practical terms, the term ‘j-graph’ will here be used more narrowly to refer to a justified graph which takes the carrier space, i.e. the outside of a building, as its root space. A ‘global’ analysis of integration will take into account each spatial unit’s relationship with each other space in the entire building; in a ‘local’ analysis, relationships with immediate and mediate neighbours up to a step-depth, i.e. a radius of 3, are taken into account. Cores of integration, both convex and axial, are defined conventionally as the 10 % most integrated units, e.g. the 6 most integrated convex sp...