![]()

1

THE DEATH OF THE AUTEUR

Orson Welles, Asadata Dafora, and the 1936 Macbeth

MARGUERITE RIPPY

In 1936, at the age of twenty, Orson Welles directed Macbeth for the Federal Theatre Project’s (FTP) Negro Theatre Unit. Undaunted by his youth, Welles facilitated a sensational success, an adaptation that infused Shakespeare’s iconic work with music and dance from African indigenous cultures.1 But the role of his collaborators, particularly the central influence of dancer/choreographer Asadata Dafora, has been overlooked. Acknowledging Dafora’s contributions to the production replaces the binary question of whether Welles exploited or supported African American artists with a more productive paradigm, one that inquires into the complexity of intercultural exchange. Such a paradigm shift opens Welles’s work to new audiences by illuminating his process of collaboration and challenging the auteurist focus on isolated creative genius.

Critics and scholars alike often privilege Welles’s name over the names of his collaborators, in part because of his success as a charismatic storyteller and promoter of his entertainment brand. But his stories of the production illuminate and distract in equal parts and often work in tandem with cultural forces to obscure his collaborative process. On the centenary of Welles’s birth, it is time to embrace the death of the auteur and acknowledge instead the polyvocal nature of creative genius. This approach turns away from questions of individual genius and toward inquiries into the collaborative nature of performance—replacing the idea of sole authorship with that of collaboration. The question then becomes not whether Welles is an auteur, but rather how the concept of auteur is itself culturally constructed, often at the expense of the identities of the many contributors to any given performance. Specifically, this chapter focuses on the contributions of Asadata Dafora and his colleague, musician Abdul Assen, whose musical performance and choreography created the sound and mood of the show, in particular through the witches’ scenes.2

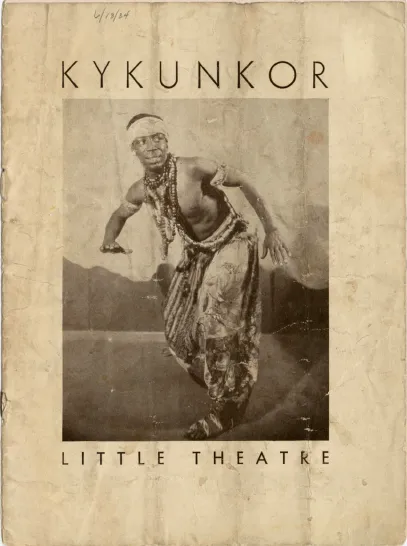

The 1936 Macbeth fulfilled two distinct roles for “Negro theater”: first, to celebrate African indigenous arts; second, to showcase the talents of African Americans within Western art forms. In 1934, the New York Amsterdam News published an article titled, “Where’s the Negro Theatre?” In this article, pitched primarily to African American readers, Romeo Dougherty lamented the lack of theater that fostered a sense of black pride. He pointed to Asadata Dafora’s Shogola Oloba dance troupe and their African dance piece Kykunkor (1934) as a positive example of such theater (fig. 1.1). FTP director Hallie Flanagan saw the performance, and decided Dafora and the influential Shogola Oloba fit the FTP mission of the Negro Theatre Unit well, and would bring needed experience with African dance form to Macbeth.3

In contrast to FTP Negro Theatre “folk” productions like Green Pastures, the 1936 Macbeth blended Western European and African diasporic forms. Welles’s concept for Macbeth, set in Haiti, employed classical Shakespearean verse spoken against a background of traditional African dance and drums. A daring risk, “Welles’s canny use of simplified elements from various black cultures,” in tandem with Shakespeare’s verse, had the “dualistic, perhaps even contradictory result” of satisfying both black and white audience members.4 Although the black community had expressed anxiety that Welles would produce Macbeth as a minstrel burlesque, this was not the result, in part due to Dafora’s choreography and the music for jungle scenes.5 As the Pittsburgh Courier noted, audiences came “to jeer, stay[ed] to cheer.”6 The negotiation among African, American, and European artistic traditions succeeded in part because Welles and Dafora worked together to create a new and dynamic blend of performance.

Figure 1.1. Photo of Asadata Dafora for Kykunkor (1934). Courtesy of Asadata Dafora Photograph Collection, New York Public Library, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Dafora’s choreography and his connection with dancer/drummer Abdul Assen—who reprised his role as a witch doctor from Kykunkor (“The Witch Woman”)—created a powerful sense of authentic Haitian “voodoo” for the audience, despite little evidence of direct Haitian influence. Assen’s work as the lead drummer and witch doctor received widespread critical praise, and he became one of the figures most associated with the production, in part because of an oft-retold tale of his conjuring a curse that killed critic Percy Hammond following his unfavorable review. This tale was retold over the years by John Houseman, Hallie Flanagan, and Eric Burroughs, as well as repeatedly by Welles himself.7 Assen’s contributions are central to understanding this performance, because in 1936, voodoo practice was advertised as a central element of this Macbeth. In this analysis, the spelling voodoo refers to staged performance of ritual and vodou to off-stage community ritual practice. Assen himself was careful to distinguish between the two—the former a harmless representation produced for entertainment, the latter a powerful spiritual tool.8

Although Dafora and Assen are often referred to in stories and reviews simply as “drummers,” by 1936, they were both established artists from different African performance traditions. Dafora emigrated from Sierra Leone, and was from a family who blended European and African traditions; Assen was a Nigerian immigrant who celebrated his connections to ritual dance and vodou. Both men described themselves as practicing Muslims on at least one program for Kykunkor.9 But the roles of both men in the production are obscured by both active and passive cultural practices of racism—what is said about them, and what is left unspoken or unrecorded. As with many actors of color in the era, they are often grouped rhetorically into composite characters, unnamed or renamed along the way. Welles is an active participant in this process, often referring to Assen and Dafora by nicknames, exoticizing rather than professionalizing them, or combining them into a composite African character.

One example of Welles’s ability to acknowledge the influence of Dafora and Assen, even as he diminishes their professional stature, comes in episode two of Welles’s 1955 Sketch Book television program. In this fifteen-minute episode, twenty years after the performance, Welles recognizes the artistic contributions of Dafora and Assen, even as he fails to recognize them as equal colleagues. Welles encapsulates their contributions in a tale he told often, that of Percy Hammond’s death via a “voodoo curse.” In part because of his fascination with magic, Welles was drawn to Macbeth‘s supernatural darkness, both in its Shakespearean context (after all, Macbeth was cursed long before this production) and in the voodoo elements highlighted in this specific adaptation.10 As Welles recounts, he chose to set Macbeth in Haiti because “above all the witches, translated terribly well into witch doctors.”11 Despite his acknowledgment of Dafora’s and Assen’s contributions, Welles refers to Assen only as “Jazbo” in this version of the Percy Hammond story, although in other versions he refers to him by name, as Abdul. It is worth quoting from this version of the Hammond curse at length, in order to capture the nature of Welles’s storytelling:

Witch doctors were specially imported from Africa because the governments in the West Indies took the view that there was no such thing as voodoo. So we had to go all the way to the Gold Coast and import a troupe. And they were quite a troupe, headed by a fellow whose name was Asadata Dafora. The only other member of the coven who had any English was a dwarf with gold teeth by the name of Jazbo. At least we called him Jazbo up in Harlem; I don’t know what his African name was. He had a diamond in each one of those gold teeth. He was quite a character. Fairly terrifying. The other members of the troupe not only spoke no English, but didn’t seem to want to speak at all. They confined their communications to drumming…. Finally the drums were ready, and the drumming began, the legend grew backstage—and indeed all over the community of Harlem—that to touch the drums, was to die. And indeed, one poor stagehand did touch a drum and did fall from a high place and break his neck. And after that, Asadata and his rhythm boys were treated with a little respect. And then we opened with Macbeth, and the drummers were fine, and the voodoo sequences—that is the witch scenes—went very well indeed, and everybody seemed to like the show. Critics were very kind to us, except … for Mr. Percy Hammond…. I was approached by Jazbo, who said to me, [heavy accent] “This critic bad man.” And I said, [offhandedly] “Yes, he’s a bad man.”

[Jazbo] “You want we make beri-beri on this bad man?” (All this dialogue’s very much like the native bearers in Tarzan and so on, I apologize for it, but it’s really what went on.)

I said, “Yes, go right ahead and make all the beri-beri you want to.”

He said, “We start drums now.”

I said, “You go ahead and the start the drums, just be ready for the show tonight.” … Woke up next morning, proceeded on ordinary course of work, and bought the afternoon paper to discover that Mr. Percy Hammond for unknown causes had dropped dead in his apartment. I know this story is a little hard to believe, [slight chuckle] but it is circumstantially true.12

This story demonstrates how Welles’s engaging anecdotes often sacrifice literal truth for the sake of a good story, as well as how his dominant personality can interfere with a full understanding of his collaborative entertainment products. While it is true that Hammond wrote a negative review on April 16 and that he died of pneumonia on the 25th, the story is striking in both Welles’s casual acknowledgement of his self-conscious blackface ventriloquism and for the contextual details he omits regarding Dafora and Assen as artists. By 1955, when Welles told this story on Sketch Book, Dafora had worked with Katherine Dunham, Pearl Primus, and Esther Rolle. He and Abdul Assen had both performed in Carnegie Hall before Eleanor Roosevelt as part of the African Academy programs in 1943, 1945, and 1946.13 Welles’s description of both men diminishes their professionalism and neglects to mention that Dafora was well-versed in both Western theatrical practice and African indigenous arts.

Dafora, truly a product of disaporic education, had studied opera in Europe as well as native dance rituals in West Africa, and had written the popular Kykunkor as an African opera two years before Welles staged Macbeth. Kykunkor, featuring the choreography and drumming of Dafora, and starring Assen as a witch doctor who issues an authentic voodoo curse on stage, embodies several parallels to the witch scenes of the 1936 FTP Macbeth.14 Although Welles suggests that both men were “imported” for the 1936 performance, Dafora had been in the United States since 1929, had founded the Shogola Oloba dance troupe, and had worked separately with Assen to craft multiple performances of African dance for a wide variety of audiences. Welles’s performance in Sketch Book creates personas that conform to stereotypes rather than reality and fails to acknowledge the depth and complexity of artistic collaboration. The story itself functions as a type of entertaining magic trick. It situates Welles at the center, as he literally speaks for his collaborators and draws their images for the viewer; he then disappears from the center of the story, making voodoo witchcraft the agent of the tale.

This Sketch Book episode effectively deploys the Hammond story both as an iconic representation of the 1936 Macbeth and to explain Welles’s own failure to complete and commercially distribute his Brazilian project, the ironically named It’s All True. He flows smoothly from the Hammond tale into a simil...