eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Comparative Media Policy, Regulation and Governance in Europe

Unpacking the Policy Cycle

This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 260 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Comparative Media Policy, Regulation and Governance in Europe

Unpacking the Policy Cycle

About this book

This book offers a comprehensive overview of the current European media in a period of disruptive transformation. It maps the full scope of contemporary media policy and industry activities while also assessing the impact of new technologies and radical changes in distribution and consumption on media practices, organizations and strategies. Combining a critical assessment of media systems with a thematic approach, it can serve as a resource for scholars or as a textbook, as well as a source of good practices for steering media policy, international communication and the media landscape across Europe.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Comparative Media Policy, Regulation and Governance in Europe by Leen d'Haenens, Helena Sousa, Josef Trappel, Leen d'Haenens,Helena Sousa,Josef Trappel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Why Study Media Policy and Regulation?

In all European countries in the last few years, an increasing number of policy choices and political decisions that directly or indirectly affect all citizens have been made with respect to the media. These decisions pertain among other things to the financing and remit of Public Service Broadcasting, hotly debated today in a number of European countries (Donders 2012; Lowe and Martin 2014); the protection of privacy as well as network neutrality in the context of Internet regulation (Stiegler 2014); the forms of public subsidies to ailing newspapers, now forbidden by the EU’s policy of banning all forms of state aid (Murschetz 2014), and so on. The aims of media and communication policy research include:

• To study what alternatives there are for media policy decision-making and how the choices are actually being made. What other aims and ways of implementation could there be besides those selected? What alternative consequences could they have?

• To clarify why and how the media are regulated today. What are the aims of media policy and media regulation, and how are they implemented in practice?

• To raise public debate on the principles and aims of media policy. What are the means and ways to influence media policy? What experience do we have of different ways of action?1

Why study media policy and regulation?

In the last several decades the European media landscape has transformed in ways that were unpredictable. New mobile gadgets and digital platforms have made television viewing and newspaper reading independent from temporal and spatial restrictions. With the rise of the Internet, the distinction between domestic and international content providers has lost its relevance. Mobile phones and tablets have increasingly become general-purpose devices that blur the line between print media, telephony and audio-visual media.

From the viewpoint of ordinary media users, these changes have offered increasing choices: new gadgets, services and channels are continuously entering the market. Simultaneously, the time spent with the media has increased, and the money spent on the media has multiplied.2 However, this has not been a natural development dictated by the proverbial free markets. Behind this turn of events lie numerous political and administrative decisions that regulate the way the media industry works and way the choices of consumers are guided. Based on different choices, media development could have progressed differently. Some decisions have resulted from European Union directives and from World Trade Organization agreements, but a majority derives from national decision-making.

The body of these decisions and their implementation is called media policy (Freedman 2008; Picard 2016). In principle, media policy affects all media functions and uses. It pertains, for example, to questions such as: How to guarantee all citizens equal access to information networks? How to secure open public access for vital information? How to protect minors from harmful media content? How to guarantee fair competition in the media markets? Closely related to media policy is the concept of media regulation (see Napoli 2001; Picard 2016). It covers questions such as: What kind of legislation concerns media and communication? How is this legislation implemented and by whom?

As an academic field, media policy is still a new research area, but it is developing fast. It has close relations, among others, to political sociology, media economy, media and communications law, media ethics and, obviously, to political studies. This shows that there are many different approaches to media policy studies. However, despite their differences, a common strand for many is a close relationship to critical, political economy of communication (see Napoli 2001; Freedman 2014; McChesney 2008; Mosco 2009; Mansell and Raboy 2011).

What do we mean by media policy?

As a research field, media policy has experienced a resurgence in the last decade. Previous periods of academic interest took place in many European countries in the 1960s and 1970s, when the topic was boosted by the increasing importance of the mass media as part of a general social welfare policy. In those days, the question was how the State could – or should – support and promote the informative and cultural functions of the media. Today, the wider societal context for media research has become close to become its previous opposite. Public economy and administration have been heavily reformed: traditional State-led regulatory structures have been demolished, State-owned companies and other public monopolies have been privatized and public services and procurements have been outsourced. This has been the case with many traditional public organizations – public utilities (such as power and water supply infrastructures), public transport, telecommunication as well as radio and television broadcasting. Along with these reforms came a need for new practical expertise and research-based knowledge. In addition to this practical interest, new critical academic research started to develop in the fields of media and communication (Prosser 2010; Kaitatzi-Whitlock 2005).

Media policy actors and media regulation

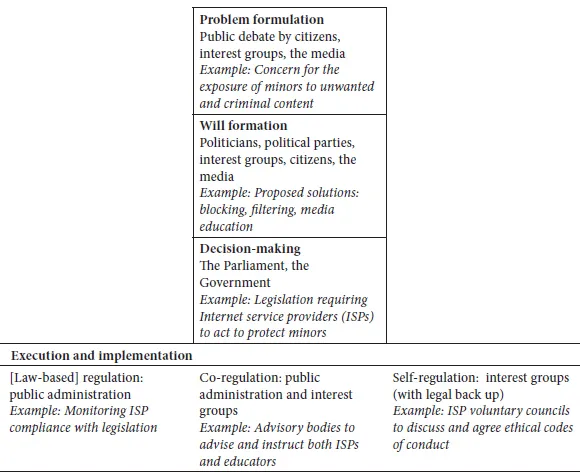

Media policy is a generic name for all decision-making concerning media and communication. In Figure 1.1, the general political process is illustrated with an example of a media-related issue. More can be found on the role of the Council of Europe in Chapter 7, and on Internet regulation and governance in Chapter 8 of this volume.

Figure 1.1: The general political process.

The political process is ideally divided into four phases. First comes the problem formulation phase, that is public debate whose participants put forward different statements and claims. Our example pertains to exposure of minors to unwanted and potentially criminal content on the Internet – such as pornography, extreme violence and child grooming. In the course of the debate, some claims start to gain support and are articulated as problems that require solving.

The second phase is that of will formation, when different standpoints and alternatives are put forward and weighed publicly. This involves all stakeholders, political parties, citizens and researchers. In our example, proposed solutions to the problem include the blocking of access to unwanted services (websites) by the ISPs, the application of filtering software in home computers that prevents the access to and downloading of harmful content, and increased emphasis on media education, directed at parents and schools. Public debate is expected to give birth to an expression of a collective will – usually registered and legitimized as the will of the majority. The media have a central role in framing and promoting the debate. Thus in the public discussion of the dangers of minors being exposed to harmful media content, for example, the way the media frame the debate and interpret the collective (or majority) will is crucial.

The third phase in the process involves decision-making, which is ultimately the purview of lawmakers, although in many cases the real decision-maker is the Government through its parliamentary majority. Here it is a question of the final choice: should we emphasize censorship of the Internet in the form of blocking access to some web pages; or should we prefer a softer solution of filtering practices, sanctioning software producers and equipment retailers; or should we rather opt for a preventive solution in the form of promoting media education and instruction.

The fourth phase is implementation, which is the responsibility of public administration. A great deal of implementation is about technical execution of what has been decided. Increasingly, however, implementation involves different kinds of regulation, that is, the guidance and monitoring of social actors based on legislation or other rules decreed by public authorities (see Prosser 2010: 2).

Will formation consists of a struggle between opposing political forces (parties). Various economic and political actors fight it out to influence the final decision-making, until a majority will be hammered out. The main actors in media policy – the forces trying to influence will formation and decision-making – can be divided into several groups, each potentially including intra-group differences and disputes (see Table 1.1).

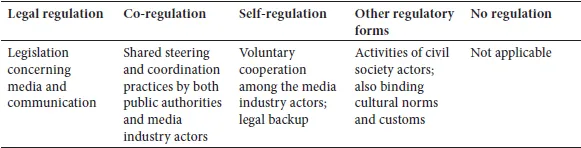

Media regulation includes all the practical means and instruments that are used to implement decisions concerning the media and their use, and to make the subjects of regulation comply with them. Strong regulation is based on legislation, that is, compulsory rules; soft regulation is exercised by self-regulatory means when the actors agree to comply voluntarily absent coercive means. Different forms of regulation can be illustrated by a continuum where one end is represented by legislation and the other by soft regulation. In-between are different forms of co- and self-regulation (see Table 1.2).

Table 1.1: Actors in media policy.

| Generic actors | Institutional actors | Special interest organizations |

| Media industry | Media companies | Industry associations, lobbyists |

| Telecom industry | Telecom companies | Industry associations, lobbyists |

| Content providers | Creators’ unions | Copyright associations |

| Advertisers | Advertising agencies | Advertising lobbies |

| Media users | Political parties | Civic associations |

| Legislator | Parliament | Political parties |

| Executive | Government | |

| Regulator | Independent regulators | |

| Media and communication workers | Trade unions | Media workers trade unions |

| Academic research | Universities, research institutions | Media research associations |

Table 1.2: Forms of regulation.

In one form or another, regulation concerns all media industry actors in the different phases of production, distribution and consumption of media contents. Content creators of different crafts (writers, journalists, photographers, composers) are all affected by copyright legislation, etc. The collection of various types of content (text, pictures, sound) and their editing (in newspapers and journals as well as in radio and television) is guided by many legal instruments, starting from copyright law and including specific legislation concerning, among others, the freedom of speech and expression and Public Service Broadcasting. Additionally, criminal law prohibits both privacy infringement and defamation. The distribution of content is regulated by legislation covering different technologies for transmitting signals and messages (e.g. terrestrial radio frequencies, telecommunication, satellites). Even the reception of media content (or media use) is governed by legislation that covers a wide range of issues, from State secrecy (both the reception and the possession of state secrets are prohibited) to consumer protection (e.g. illegal contracts concerning mobile subscriptions) and piracy (acquiring and holding illegal copies of copyrighted works).

Why do we need regulation?

Why and for what do we need regulation? Is regulation even necessary at all? Does it not mean interfering with the free functioning of the media markets and the free choice of media consumers? Three types of justification are generally applied: regulation is needed to promote democracy (public interest), secure the functioning of the market (fair competition) and guarantee the compatibility of various media technologies (standardization) (see also Prosser 2010: 17–18).

1. Public interest: The role of the media in promoting democracy has been assessed in different ways on different occasions. Unregulated commercial competition is often seen as a threat to a balanced e...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Why Study Media Policy and Regulation?

- Chapter 2: Is Content Still King? Trends and Challenges in the Production and Distribution of Television Content in Europe

- Chapter 3: Media Economics and Transformation in a Digital Europe

- Chapter 4: Media Governance: More than a Buzzword?

- Chapter 5: Subsidies: Fuel for the Media

- Chapter 6: Public Service Media in Western Europe Today: Ten Countries Compared

- Chapter 7: The Europeanization of the European Media: The Incremental Cultivation of the EU Media Policy

- Chapter 8: The Council of Europe: Ensuring the Freedom and Independence of Europe’s Media

- Chapter 9: Europe’s Internet Policies: The Challenge of Maintaining an Open Internet

- Chapter 10: Media and Democracy: A Couple Walking Hand in Hand?

- Chapter 11: Media Diversity and Pluriformity: Hybrid ‘Regimes’ across Europe

- Chapter 12: Testing the Boundaries: Evolving Norms and Troubling Trends for Journalism

- Conclusions and a Message to Our Respected Readers

- Notes on Contributors