- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Marie Rose Wong peers through the lens of single-room occupancy (SRO) hotels to capture the 157-year origin story of Seattle's pan-Asian International District. This gorgeous, meticulous book layers together interviews, maps, and insights from over a decade of primary research to provide an urgent history for Asian American activists and urban planners.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Building Tradition by Marie Rose Wong in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Asian American Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Asian American Seattle and the Laws of Land | 1 |

Platting the City of Seattle began shortly after the 1853 arrival of the Denny Party, a group of settlers that included the families of Arthur Denny, Asa Mercer, Carson Boren, and Charles C. Terry. With the specific intention of developing a town site, the Denny Party seized the opportunity to acquire land through the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850. Section 4 of the Act promoted homestead settlement in the Pacific Northwest by offering an opportunity for land ownership and the profit that could be made from property with a modest investment of time. The Act linked the importance of nationality, race, and citizenship to property ownership. In part, it “granted to every white settler…being a citizen of the United States, or having made a declaration…of his intention to become a citizen…the quantity of one half section…of land….”1

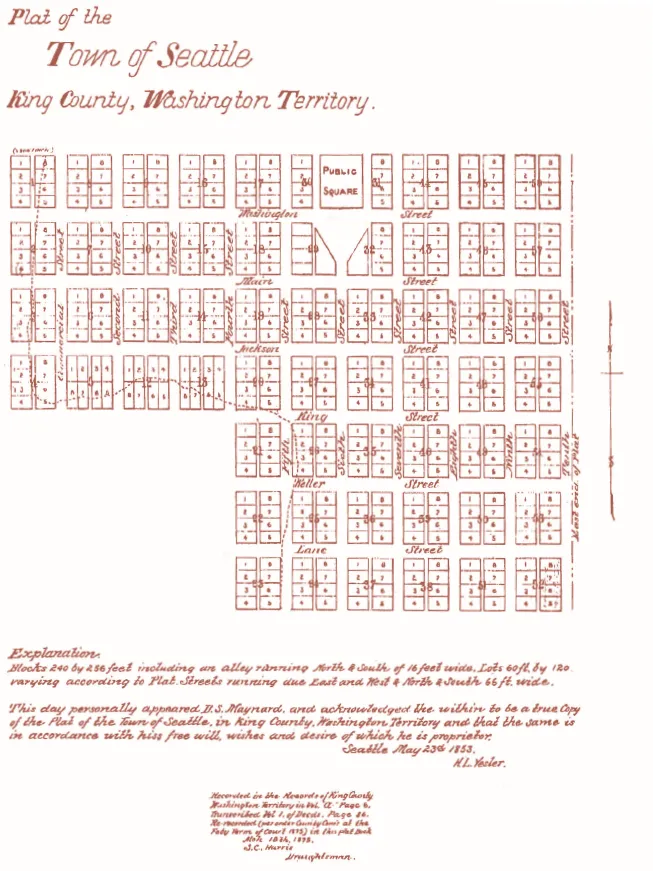

The first two plats of Seattle were filed on 23 May 1853. Arthur Denny and Carson D. Boren established a grid pattern on land that ran parallel to the shoreline of Elliott Bay, and David Swinson “Doc” Maynard aligned a second and separate grid pattern that was designed to a true north–south orientation. The east-to-west road known as Mill Street acted as a “seam” that joined the two plats, but the resulting connections of north–south-running streets did not always find a ready or easy alignment.2 It was the unofficial but acknowledged boundary that divided the commercial, business, and financial center that was developing to the north from the south downtown. Far more wooden-framed buildings were constructed and the city had laid almost three times the number of wooden-planked sidewalks in the area north of the Mill Street “dividing line.”3

The real significance of these two separately-filed grid plans went beyond the street alignments and directional orientation in that each of these plats was thought of differently when it came to the development type, identity, and reputation of Seattle’s central city real estate, and the economic class and race of people who lived and worked there. Whether related to the legend and reputation of Maynard as a man who had a high tolerance for a bawdy lifestyle and vice within the City, or from the evolving laws and lawlessness in the first century of Seattle’s history, Maynard’s Plat was referred to in polite society as that area “below the line” and the line was Mill Street.

In 1870 and in one of the earliest city directories for Washington Territory, the area south of Mill Street was recognized as the “Lava Beds…a slang term applied to the saw-dust fill…[and the] wild and unimproved land.”4 The geographic area that was created by Mill Street to the north, 14th Avenue South to the east, Dearborn Avenue to the south, and 1st Avenue South as the western boundary was shared by gamblers, thieves, drunkards, transients, sex workers, and Asian Americans who thought of the area as home.

Seattle had established a strong urban presence from building industries that capitalized on the natural resources of the Pacific Northwest. The development of the cannery industry, coal mining, farming, and lumber mills helped build and sustain the economy of the city and the state. The location of the city, port, and railroad transportation systems enabled the movement of goods that met product demands in the national and international markets, and this opportunity encouraged people to come and seek work and personal fortunes in Seattle.5 Among these Pacific Northwest immigrants were the Chinese, Japanese, and Filipinos who came in steady and overlapping waves. Asian American settlement began with one Chinese person that was recorded in both the 1850 and 1860 Washington Territorial Census and prior to the incorporation of the City of Seattle on 2 December 1869.

With a modest beginning as a settlement site supported by Henry Yesler’s 1853 Sawmill, Seattle quickly became the largest city in Washington Territory. In the 1870s and with a population of about 1,200, Polk’s Oregon and Washington Gazetteer reported that the city was already well-established with city utilities, newspapers, coal mine development, and transportation and communication advancements that included graded streets, steamship lines, a telegraph system, and the construction of railroads in Washington Territory as a result of decades of planning.

MAP 1-1: Maynard’s Plat, 1853 [Records of King County, Washington Territory, Volume A, page 6, King County Assessor’s Office]

Consideration of a cross-country rail line connecting the East Coast to the Puget Sound had been proposed as early as 1845, but it wasn’t until 1864 when Congress gave charter to the Northern Pacific (N-P) Railroad. By this time, plans for construction of a line that would connect Minnesota with a not-yet-disclosed terminus in Washington Territory were delayed by other political and national economic demands, including the Civil War. Laying portions of track at opposite ends of the N-P line began in 1870, the year after the completion of the Union Pacific as the first transcontinental railroad, but the terminal location of the line on the Puget Sound was still uncertain.6

An initial arrangement was made to bring in 7,000 Chinese laborers to begin work on the N-P rail line. This and the increasing number of canneries developing along the Columbia River and in Alaska provided seasonal employment for a growing number of Chinese workers. Seattle and Portland were major employment centers for labor contractors in the Pacific Northwest.

By the 1870 Census, 234 Chinese were recorded, with the majority of them living in the eastern part of the Washington territory.7 Initially, many of the Chinese who settled east of the Cascade Mountains were working as gold miners and were later employed west of the mountains where they found opportunities working as domestics and in farming, lumber mills, the fishing and cannery industries, and setting rail lines. The Territorial Census for King County indicated that 32 Chinese males were living in Seattle by 1871.8 Between the ages of 20 and 39, they were employed as cooks (10), laundrymen (8), sawmill workers (7), cigar makers (2), and one tea merchant.9 A few years later, Seattle’s Daily Pacific Tribune noted the strong likelihood of a discrepancy in the count of the total number of Chinese that were settling in the city with the county census indicating “a [total] population of 2614 persons, 1512 of whom are credited to Seattle…. The town is reported to have 842 white males of all ages and 636 white females; 24 colored males and 10 colored females. The idea of there being only 34 colored folks in Seattle! There are at least five times that many Chinese alone.”10

In 1872, Seattle offered the Northern Pacific Railroad 3,000 acres of land, 7,500 town lots, and $250,000 in bonds and cash if it were selected to be the terminal city of a rail line that would traverse the Western United States from Minnesota. But Seattle lost the bid for selection when a final decision was rendered in 1893 that selected Tacoma, a less-populated city thirty miles to the south.

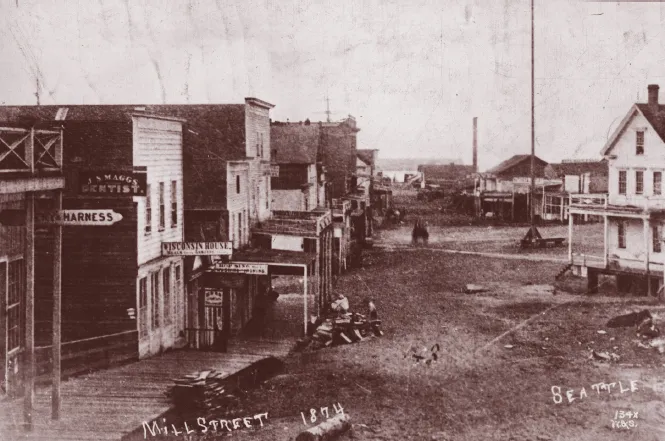

Hop Sing Laundry, 1874. One of the earliest images showing the Chinese business community in what became the core of Seattle’s early Chinatown. This location was to the northeast of the early Wa Chong business that was at 15 Mill Street and west of Commercial Avenue. [Courtesy The Seattle Public Library, spl_shp_23074]

In a series of independent ventures that took the focus away from the N-P terminal loss, Seattleites focused on the business of funding and constructing their own local spur railroad lines and expanding ports on the waterfront to take advantage of growing commodity markets. Lumber from the Pacific Northwest was in demand in rapidly growing cities such as San Francisco, and as the prominent city of the Territory, Seattle was a supplier of goods, services, and labor for the growing cannery industry in Alaska.

By 1876 and as the Chinese were becoming more noticeable, editorials were drawing public attention to what they viewed as an alarming increase in the number of Chinese in Seattle. The Seattle Business Directory indicated that there were “250 Chinamen in [the] City” and twelve Chinese businesses, the majority of which were clustered around Washington Street between 2nd and 3rd Avenue South.11 The Daily Intelligencer offered this opinion in an 1876 editorial entitled “Too Many Celestials.”

…so large a number of Chinamen are flocking to our city that we are receiving more than our share of this undesired class of emigrants…about twenty Chinamen arrived. They marched up Mill Street in single file, with their bamboo sticks across their shoulders, and attracted a great deal of attention. [They]…came from Portland, and were among many who recently arrived at San Francisco from China…. What is to be done with so many Chinamen?…this large influx of labor alarm[s] the laboring classes…. We would be better without them…the law of finance has its application to peoples as well as currencies, and that is, in the labor market an inferior race will drive out a superior one. If Chinese immigration continues…their disguised slavery…will take the place of free white labor in all the trades and lines of production and manufactures…. Chinese labor is, becoming more unpopular every day.12

Although they were clearly unwanted, it was believed that the labor market and hiring practices would ultimately serve to discourage their settlement. Comparatively speaking, figures for 1878 indicated 210 Chinese in Seattle that accounted for less than 4.5% of the total 4,681 population of the City.13 In fact, capitalists who were building Seattle kept employing the Chinese as railroad spur lines continued to expand in the Pacific Northwest. Seattle was identified as not only the largest but “the leading city of the territory.”14 In 1880, the Seattle & Walla Walla was purchased and reorganized as the Columbia & Puget Sound Railroad by Oregon rail magnate Henry Villard. Villard constructed another spur line that connected present-day Auburn with Seattle and spent the next decade in a flurry of activity that included hiring 6,000 Chinese to complete a line that would connect Portland with California by the end of 1883.15

CHINATOWN AND THE WA CHONG COMPANY

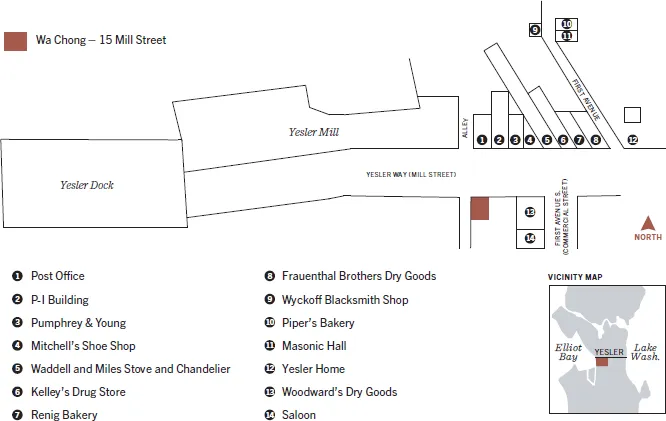

Chun Ching Hock arrived in the United States in 1863 when he was 18. Born in Long May Village, Sunning District, China, Chun travelled from San Francisco to Portland and arrived in Seattle to begin his career as a wholesale and retail merchant, labor contractor, and ultimately a property owner. The personal needs of the Chinese railroad and cannery laborers were provided by a few scattered businesses near the tideflats at Commercial and Mill Streets. Two of the earliest businesses at this location included a cigar manufacturing company that was operated by Chinese as early as 1866 and a mercantile store that was begun by Chun in 1869 on property that had been leased to him by Henry Yesler and across from the sawmill.16 Chun’s store offered an array of services and merchandise and was called the Wa Chong.17 It was the beginning of his long-term commitment as a leading merchant and a founder of the Chinese settlement in Seattle. Of tremendous importance, the Wa Chong Company was also the beginning of corporate identity that would allow the purchase of land by aliens ineligible for citizenship, a tactic that would benefit Asian immigrants from China, Japan, and the Philippines.

MAP 1-2: Wa Chong Store, Seattle – 1870 [Author]

Chun’s first recorded property purchase was in April 1871 when he relocated the Wa Chong store to the NE corner of 3rd Avenue South and South Main Street and out of the tideflat area. The 1871 Seattle Directory recorded four additional Chinese businesses in the Wa Chong vicinity, all of which were “China Wash-houses.”18 By 1872, the number of washhouses increased to seven with six other businesses that included two chop houses, one drug store, and...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Dedication

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 Asian American Seattle and The Laws of Land

- 2 Prosperity “Below the Line”

- 3 The Business of Building Residential Hotels

- 4 The Neighborhood of Asian American Hotels

- 5 Behind Those “Ordinary” Walls

- 6 The Death Knell of the SRO Residential Hotels

- Epilogue: The Legacy of the SRO Hotels

- Acknowledgements

- Bibliography

- Index