![]()

Act i

‘The question isn’t “What are we going to do?” The question is “What aren’t we going to do?” ’

FERRIS, FERRIS BUELLER’S DAY OFF (1986)

![]()

5.

Thunderbirds Are Go

‘Roads? Where we’re going, we don’t need roads.’

EMMETT ‘DOC’ BROWN, BACK TO THE FUTURE (1985)

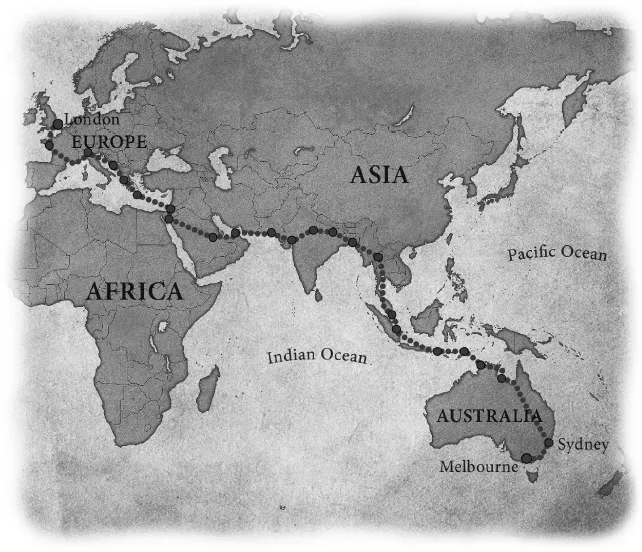

The Smith family had a meal together on the morning the Southern Sun left for London. After a restless sleep, Anne, Jack, Tim and I sat alone on the deck at the Royal Yacht Club of Victoria, where the Sun was waiting inside her yard, fully fuelled and provisioned.

The breakfast was quietly emotional and meant the world to me. It was a Sunday in the middle of autumn. Melbourne was starting to turn cold, although rays of morning light reflected off the clear waters of Hobsons Bay. Boats bobbed back and forth in the foreground, and office towers glinted in the distance. I was leaving a peaceful, familiar world.

Tim, who had just turned eighteen, exuded an understated emotion I had rarely seen in him before. He kept reaching out to touch me across the table. Anne, who had always supported my dreams, no matter how self-focused they were, was affectionate too. She was going to miss me, but wasn’t worried for my safety. She didn’t even think it was an unusual thing to do; perhaps I hadn’t mentioned that no one had done it before. But I was very apprehensive, which I think Tim sensed. Poor Jack had a cold, so his presence meant even more to me. We said goodbye on the boat ramp.

‘Have fun, and be safe,’ Anne said.

‘Please be careful, Dad,’ Tim said in his soft voice.

I quietly promised them that I would, hoping it was true. The knot in my stomach told me I was nervous. I felt an overwhelming responsibility to them to return.

They stood back. I climbed into the Sun and started the engine, drove down the ramp into the bay and slowly taxied to the end of the marina, all the time worrying over whether I had remembered everything. The manual said the Sun had enough power to lift off from the water, even though the plane was carrying more weight than she ever had before. I wasn’t certain she would get into the air.

As the last gauge turned green, I looked over to see Anne, Tim and Jack at the end of the marina, waving goodbye. I lined up into the wind and pushed the throttle all the way forward. The Sun accelerated smoothly through the water. As she picked up speed, I gently pulled on the stick and she rose into the sky. I circled over my family as I climbed, rocked my wings to bid them farewell, and continued into the sky.

It was the start of a quest ten years in the making, but one that even my closest friends didn’t know about. Or my mother. It was time to fess up.

I turned to the east. My first stop was to be Raymond Island, ninety minutes away, in the Gippsland Lakes region of eastern Victoria. My mother had holidayed there as a child, a tradition she passed on to her family. As kids, my brothers and I would get up early on Sunday mornings to watch Thunderbirds in bed with our father. Dad passed away much too young many years ago, and Mum retired to Raymond Island with her new partner, Alex. They have six waterfront acres, which they share with kangaroos and koalas. There is no bridge to the mainland. Access is by ferry, boat or – in today’s case – aircraft.

I had let Mum know the day before that I might be dropping in. A few minutes into the flight, as I levelled off at 1500 feet, just above the height of the city buildings a few kilometres off to my left, I texted her to say I would be there soon for coffee. I scanned the horizon through the busy airspace over the eastern suburbs of Melbourne. Moorabbin airport was to my south, Essendon airport to my north and Lilydale airport out to the east. But mostly I was still thinking about my family. It occurred to me we hadn’t thought to take a family photo with the Sun before I left.

After half an hour, the Sun settled in at 3500 feet. There was some military airspace near Mum’s island, but it wasn’t operational on Sundays, which meant I could fly straight to her place. I sent her another message, this time from my iPad. It was a link to the online journal I had set up, which had an entry explaining my plan to fly to London. I suggested she might like to read it before I arrived. I flew over our Sun Cinema in Bairnsdale, and descended towards Raymond Island, following the Mitchell River downstream.

I landed on the waters of Lake Victoria, right in front of Mum’s house, lowered the wheels and drove up onto the sandy beach. She was standing on the foreshore, and I saw Alex making his way through the tea-trees. I shut the Sun down, climbed out and walked over to Mum. We said hello and I gave her a hug.

‘Michael, what are you up to now?’ she asked with a worried smile.

Several large kangaroos lay in the sun while we drank coffee on her deck. I explained the dream I’d had for ten years, the planning that had gone into it, and what I was going to do. I expected more questions, but she was subdued. Perhaps it was all a bit overwhelming. As midday approached I needed to keep going, and Mum’s farewell was similar to Anne’s: ‘Have a great trip, but please be careful.’

I later learned that, as I took off from the water, Mum had said to Alex, with a tear in her eye, ‘That might be the last time I’ll see him.’

The Southern Sun followed the stunning yet sparsely populated coast around the south-east corner of mainland Australia at 1500 feet. We passed Gabo Island and some of Victoria’s remotest seaside villages.

Whether you’re sailing or flying, following the beach from Melbourne to Sydney is not only beautiful, but easy navigation – just keep Australia to your left.

My first night was spent in Wollongong, a small city half an hour’s flight from Rose Bay in Sydney Harbour, where the original Qantas flights began. I walked to a local hotel and had a simple and comforting dinner with two Sydney friends, Ian and his partner, Sophie, who’d driven down to meet me. I felt a great relief at finally being on my way. Nonetheless, I was nervous about the landing on Sydney Harbour the following day.

On such a large body of water, strong winds and waves can make landing difficult. To minimise the risk – the winds are usually calmer in the morning – I took off at sunrise, when the air was crisp and a golden light bathed the Sun. I followed the coast north, all the way to the harbour. Because of the nearby Sydney airport – named after the first pilot to fly between the United States and Australia, Sir Charles Kingsford Smith – all light aircraft on the coastal route are required to fly along the beaches, at or below 500 feet. The morning was a gorgeous one, so it was like being told to stay up late, watch movies and eat ice cream. If you insist!

The good weather didn’t hold, though, and when I was over Port Jackson, the original and little-used name for the water lapping on central Sydney, I saw that the city was enveloped by rain. I flew between the Heads, at the opening to the harbour, and in a gentle arc I passed the Sydney Harbour Bridge and the Opera House on my way back to historic Rose Bay.

The water was choppy but the landing unexceptional. I drove up onto the hard-packed sandy beach. Towering above me were six-storey apartment blocks, populated by people in various states of undress. Some waved. (For the record, the wrong people had little or no clothes on.)

Rose Bay became Sydney’s first international airport in the late 1930s. Qantas built a passenger terminal for the London flights, which were undertaken in British-built Short C-class flying boats, better known as Empire Flying Boats. One of Sydney’s finer restaurants, Catalina – the name of another famous flying boat – is located right there, over the water. A modern air terminal caters to seaplanes that fly up and down the coast, mostly for tourist sightseers or wealthy Sydneysiders avoiding the beach traffic.

My friend Ian Westlake met me on the beach and gave me a letter to deliver. It was a handmade airmail envelope from his partner, Sophie, addressed to her grandmother in England. Airmail by flying boat had returned. I suddenly wished I’d thought to collect a few more letters to hand-deliver to Old England, in homage to my predecessors.

After a few minutes on land I was back in the Southern Sun, taxiing into the water. Apart from several oblivious locals, Ian was the only observer of the official beginning of my attempt to retrace the 1938 Qantas route. He also witnessed my first stupid mistake.

The water was rougher than I had hoped, but not so much that it was dangerous. The Sun is designed to lift off at 45 knots; in rough sea, it takes longer to reach that speed because the waves hit the hull and slow her down. If the waves are too big, it can even be impossible to take off, and the aircraft can be swamped.

I taxied out a fair way into the harbour because I wanted ample room to build up speed. Ferries plied their routes in the distance. Just as I was about to line up for take-off, the Sun bumped into a sandbar. I felt a shudder go through the plane, but thankfully we passed over it and continued on.

The momentary collision could have been a lot worse. If the water had been just a few inches shallower, the Sun might have got stuck. If she’d hit the sandbar while accelerating at full throttle during take-off, the hull could have been damaged, or even holed. It was worrying that, at the symbolic start of my trip, things were already close to going wrong.

Every pilot – amateur, commercial or military – must conduct several basic checks before taking off. In my case they were known by an acronym, GIFFTT, which stood for ‘Gear, Instruments, Fuel, Flaps, Trim, Trim’ – or, in slightly longer form, landing gear, instruments, fuel pumps, flaps, elevator trim and propeller trim. The wheels had to be up to reduce drag, the instruments had to be working and set correctly, both fuel pumps had to be on, the flaps had to be lowered to make the wings more effective at low speeds, the elevator flaps on the tail had to be trimmed (or adjusted) for climbing, and the propeller had to be angled for maximum thrust. But in a hurry to get started, and flustered by the sandbar bump, I foolishly skipped these essential checks.

The Sun ploughed through the harbour into the wind. Everything seemed fine, although she took longer than usual to build enough speed to take off. As she climbed through the sky, I reached for the lever to reduce the amount of flaps, which are used at take-off and landing because they provide more lift, allowing the plane to fly more safely at a slower speed. The lever was already in the upright position. I hadn’t extended the flaps, which meant the Sun had been forced to go about 10 knots faster than otherwise needed to take off. The higher speed had increased the dangers if she hit a big wave or sandbar. By cutting corners, I had committed one of the ultimate rookie errors in aviation: an inadvertent flapless take-off.

Through gritted teeth, I berated myself. ‘I must follow procedures and take my time – there really is no rush,’ I told myself.

It was an inauspicious beginning.

My destination was Longreach, the town where the Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Services Ltd was founded – the airline that came to be known as Qantas. For me, the day’s route would function as a kind of test flight: the 800 miles, nearly 1500 kilometres, was likely to take ten and a half hours. It would be the longest leg of my journey to London, and the longest of my flying career. I wanted to be on home ground for this physical and mechanical test.

After quickly refuelling at Cessnock, in the Hunter Valley, we climbed easily to 8500 feet, where a tailwind propelled the Sun along. We climbed another 2000 feet, where the winds were even more favourable. The original Qantas flying boats generally cruised at around 5000 to 8000 feet. (By contrast, modern airliners operate at around 30,000 feet and above.) It wasn’t long before I found that the Sun’s wings weren’t designed to perform in the thinner air. Any lapse in concentration by me at the control stick and she would slip a few hundred feet, which was neither professional nor efficient flying. I found it easier back down at 8500.

To my frustration, I discovered the propeller couldn’t be adjusted in flight because of some fault. Altering the angle of the blades at different speeds can make them more efficient, much like changing gears in a car. I was becoming concerned that the Southern Sun wouldn’t make it to Darwin, let alone to London. (It turned out the problem was easily fixed by re-crimping a loose cable.)

I arrived at Longreach fifteen minutes before dark, and circled a few kilometres from the field while a Qantas passenger flight landed. The Sun had three hours of fuel left, which was incredibly reassuring. Fuel exhaustion was one of the biggest killers of early long-range pilots.

A charmless motel was adjacent to the airport. I checked into a basic room that would turn out to be the most expensive of the trip. I spent the evening quietly; in what would become a typical routine for the journey, I prepared my next day’s flight plan and dined alone.

The next morning I walked over to the airport before dawn, refuelled and made another stupid mistake. I dragged a small aluminium ladder to the side of the Sun, climbed it and checked the oil level in the engine. There was plenty. Reassured, I got into the plane, performed my pre-flight checks and started the engine. Immediately there was a loud clunk from outside the cockpit.

I swung my head from side to side, frantically...