![]()

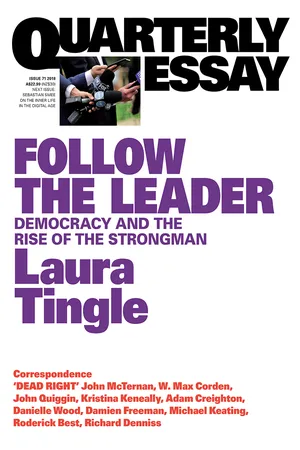

FOLLOW THE LEADER | Democracy and the Rise of the Strongman |

| | Laura Tingle |

London, June 2017. A leadership crisis is upon us. Having cheerfully followed my lead as we clambered over the remnants of ancient Roman civilisation at the beginning of my first Quarterly Essay, Great Expectations, and contemplated Tacitus and the fall of the Roman Empire at the beginning of my second, Political Amnesia, Tosca Ramsey, my daughter, my diva filia, has had enough as we travel on perhaps our last Excellent Girls’ Adventure abroad together. Now almost nineteen, Tosca has perfected the teenage eye-roll and barely disguised contempt. “Oh. My. God,” Tosca says, as I prod helplessly at a ticket machine in the vast concourse of Waterloo Station. “I can’t believe you just did that.” She strides off to sort out our ticket purchases, gloriously unaware of the young men walking into poles and garbage bins as she passes by. Although oblivious to the path of male destruction she leaves in her wake, she is more than aware of the effect she is having on her mother: the assertion of independence; of greater knowledge of the world and what is needed to operate in it; of greater competence and capacity to lead us on the next stage of our journey. Happy to follow along on our past adventures, in this one my girl has nicked the field marshal’s baton from my knapsack and made a charge for the front.

Leadership, it turns out, is a two-way thing. Leaders kid themselves that they are setting the terms of play, even running the world. And we write and think about them in those terms. But in fact true leaders only get to lead if they have followers whom they can persuade to follow. So often it is what followers want that determines whether leaders get to emerge at all. And as we have seen in Australia in recent years, it is followers in the party – and what they think followers outside the party – want that determines whether they stay there.

I didn’t yet realise, when I was being bathed in scorn at Waterloo Station, that there was an obvious final instalment, a trilogy to complete, in the consideration of Australian expectations of government, and our failing institutional memory, that I began in 2012. That final instalment concerns political leadership in the modern world. For whatever our expectations of government, whatever the state of our institutions and institutional memory, it is leadership that helps both to settle those things, and change them.

We don’t much discuss our expectations of government, or consider the changing nature of the institutions that hold our society together, and so often we have faulty memories of what has gone before. But we do increasingly focus our frustration with our society and our politics on the human form of our leaders. We bemoan a lack of leadership. Some yearn for the good old days when we had it. Yet when we get it, we sometimes don’t recognise it, and even if we do, we seldom reward it.

People always grumble about political leaders. But there is a deeper malaise afoot now. Zoom out from the daily inanity of the domestic news cycle. Zoom out even further from the point where you shake your head in disbelief at Trumpian political developments around the world or local Liberal Party madness. Consider something a little unlikely as a sign of our leadership discontents.

Young people’s fiction these days comes in ever faster waves of franchises seeking to ride particular crazes: for wizards, zombies, vampires or the post-apocalyptic. In many of these books, TV series and films, the same themes recur: societies in which the rules have broken down, in which there are no people in positions of authority, or even formal leadership structures. These are stories built on disillusionment and a suspicion of social structure – which often acts as a threat to our heroes, who invariably are just average kids. Rugged individuals must make do, striving to stay alive, at least until the end of the book or episode.

Our young people absorb, but are also attracted to, these worlds with their broken-down societies or absent leaders. This might be no more than a reflection of the slightly maudlin phase many of us go through as teenagers. At first glance, an obsession with the post-apocalyptic would seem more understandable in those of us who grew up during the Cold War, rather than the second decade of the twenty-first century. But the disillusionment reflected in fictional domains coincides with the global return of the strongman to politics. And with these two conflicting trends comes a belated alarm that the world is not naturally tending to the Western democratic model that many of us smugly assumed had triumphed and become irresistible at the end of the Cold War.

*

In so many ways, the qualities and requirements of leadership are eternal. We have all read about the great figures of history, and that reading has shaped our views of what makes a true leader. But if I’m right about the changing expectations we have of politics – and if our institutions and institutional memory are being transformed – then there is much to say about how those human beings who have a will to influence others, and to power, rub up against the forces at play in modern politics.

This essay considers those forces, and how leaders and leadership are responding to them. It is just too easy to say our current leaders aren’t up to scratch (even if they aren’t). We need to have a more sophisticated discussion about what they might lack and how we judge what they need to give us. But instead, when our young people look back at the real world, they see a deep cynicism about political leaders but also an unhealthy obsession; and a focus not so much on what they might have achieved for their communities, but merely on their personal traits.

In Australia, for example, the recent debate about Adani’s controversial proposed coalmine in central Queensland descended at one point into a discussion of Bill Shorten’s personality and honesty, rather than the merits or risks of the massive project. It became a discussion of the different messages Shorten sent to different audiences and what this told us about his character.

Similarly, Malcolm Turnbull’s prime ministership was overwhelmingly considered in light of his personal qualities and life story, with little regard given to the circumstances that constrained or shaped his day-to-day political management, let alone that the prime ministership is but one dynamic in a larger play of political forces. Turnbull’s fractious and self-indulgent Coalition partners in the Nationals, the reckless wrecking of Tony Abbott: we just wanted the prime minister to make these things go away, or to govern as if they don’t exist, just as we expected the same thing of Julia Gillard when it came to the realities of minority government.

Consider the Nationals. John Howard had leaders Tim Fischer and John Anderson to deal with. Tony Abbott, and in the early days Malcolm Turnbull, had Warren Truss. These men were sometimes idiosyncratic, sometimes dull, but ultimately committed to the Coalition and making it work.

Self-indulgence on a grand scale is a relatively recent thing in Australian federal politics. Of course, individuals have long blundered through the narrative from Canberra, causing chaos for the government or Opposition of the day, and providing colourful copy for journalists. From Jim Cairns and his “kind of love” for Junie Morosi, to Barnaby Joyce and his victimhood view of his imploding personal life, there has always been something colourful to watch in federal politics. But until the last ten years, politicians largely acted on the understanding that their individual actions ultimately had to take into account the good of the party and the survival of the government.

Not anymore.

The tearing down of Malcolm Turnbull’s prime ministership has been perhaps the most incomprehensible example of this. Turnbull was destroyed by people in the Liberal Party who, whatever they said about trying to save the government, were actually prepared to lose it to achieve their ends.

Whether or not Barnaby Joyce was a more politically effective leader of the Nationals than some of his predecessors, the untrammelled licence with which he has approached his career – and the fact there were so few signs of commitment to making the Coalition with the Liberal Party, and therefore the government, function successfully – make him the embodiment of the new self-indulgence. He was committed to havoc from the time he entered federal parliament as a senator in 2005.

Labor has had its own waves of self-indulgence, notably in the vengeful form of Kevin Rudd. Though he was himself a victim of the factions, his downfall as prime minister followed a very short period of disloyalty, which stands in stark contrast to his own relentless undermining of his colleagues. Julia Gillard as prime minister had the smallest of circles of ministers on which to rely in government, with Rudd and his colleagues constantly circling.

Once Bob Brown left the Senate, the Greens – a bit like the latter-day Nationals – did not seem to have the pragmatic understanding that the end of Labor government would limit their capacity to influence policy.

It’s not a question of feeling sorry for Turnbull or Gillard, but of understanding that a lack of internal discipline and room to manoeuvre circumscribes what leaders can do before they even get out of bed in the morning. Instead of such problems being recognised as impediments that have to be dealt with, they tend to be treated as not just the leader’s own fault, but also a sign of weakness. Thus, even as the Nationals and the conservative rump of the Liberal Party provide the daily colour and debacle of today’s episode of The Young and the Restless, the trend is still to focus on the leaders, rather than those around them. The discussion becomes a one- or two-man play under a single spotlight, instead of a chaotic musical where the whole stage is lit to reveal an all-star cast, an unruly chorus and a Wagnerian-sized orchestra. How likely is it that we will understand what is really driving events when we view them this way?

Until relatively recently, the idea of collective cabinet government set the frame for federal politics in Australia. Prime ministers may always have been first among equals, but the discussion was about how the prime minister wrangled the views of his colleagues, or led them to a particular view, as the first best exemplar of wider consensus-building. Alternatively, the narrative may have been about the tussle of a particular minister to sway his or her colleagues, or a battle among ministers for policy supremacy.

But now it is a leader who succeeds or fails alone.

Yet, in Australia at least, the evolving structures of our government – particularly the complexities of Federation – have reached a point where it is simply not possible for any one person to bring about a dramatic change in complex national policy (if it ever was), no matter how persuasive an advocate they might be, or how clever they show themselves to be at manipulating the system.

It’s not that dramatic change isn’t possible. It’s not that we ultimately don’t need someone to set a direction. It’s just that any sort of transformation requires not only that a leader master the mechanics of two levels of government and the circumstances of the day, but also that the rest of us have a clear-eyed understanding of all the factors a leader must manipulate in order to bring about that change – so that we can decide whether we will follow, and what we really think of the person leading us.

Complex change, involving several levels of government and a multitude of political interests, requires more political time and space than we seem prepared to give our leaders these days.

Francis Fukuyama wrote recently:

Liberal democracies invite popular participation and over time tend to proliferate rules that complicate decision-making. When such political systems combine with polarized or otherwise severely divided publics, the result is often political paralysis, which makes ordinary governing very difficult. India under the previous Congress Party government was a striking example of this, where infrastructure projects and needed economic reforms seemed beyond the government’s ability to deliver. Something similar occurred in Japan and Italy, which often seemed paralysed in the face of long-term economic stagnation.

One of the most prominent cases was the US, where an extensive set of constitutionally mandated checks and balances can be seen as a “vetocracy,” i.e. the ability of small groups to veto action on the part of majorities. This is what has produced a yearly crisis in Congress over passing a budget, something that has not been accomplished under so-called “regular order” for at least a generation, and has blocked sensible reforms of health care, immigration, and financial regulation.

This perceived weakness in the ability of democratic governments to make decisions and get things done is one of the things that set the stage for the rise of “would-be strongmen” who can break through the miasma of normal politics and achieve results. This was one of the reasons that India elected Narendra Modi, and why Shinzo Abe has become one of Japan’s longest-serving prime ministers. Vladimir Putin’s rise as a “strongman” came against the background of the chaotic Yeltsin years. And, finally, one of Donald Trump’s selling points was that, as a successful businessman, he would be able to make the US government functional again.

In other words, it is not just we who are experiencing these symptoms of paralysis.

There was much of the appeal of the “would-be strongman” in the election of Tony Abbott in 2013. Having fomented an air of chaos, weakness and dysfunction around the man he deposed as Liberal leader, and then around the Rudd and Gillard governments, Abbott promised voters he would lead a government that would be “back in charge.” Issues that had seemed to run out of control, not just of government but of voters, would be put back in their box: “boat people”; the “carbon tax” he argued the government wanted to introduce; national debt; expensive government projects; red tape.

Australia voted primarily for an end to the sense of chaos around the Labor government, but never quite embraced Abbott’s strongman tactics in office, particularly when they were turned against voters themselves in the punitive 2014 Budget.

Turnbull’s return to the Liberal leadership in 2015 could be seen as a rejection of the strongman, even if there was a yearning that he should shift politics back to some central place, from which it had been dislodged by Abbott.

Voters’ frustration with Turnbull was not primarily over policy paralysis but because of a lack of any clear policy at all, or at least of the sort of policies many thought he would introduce. It was not complicated rules that thwarted Turnbull, nor a community-wide “vetocracy,” but a “vetocracy” within his own parliamentary party. Turnbull’s inability to wrangle these internal political forces – or perhaps his refusal to ostentatiously stare them down – left voters frustrated and ate away at his authority. The leadership challenge from Peter Dutton that emerged in August 2018 only highlighted all these trends: the self-indulgence, the lack of any commitment to collective responsibility; the complexity of policy issues; polarised and divided electorates; the slow undermining of prime ministerial authority. And, ominously, it pointed to the prospect of another tilt to the right, to populism and to strongman politics.

Finding a way to deal with these trends, something that eluded Malcolm Turnbull, was the real task facing Scott Morrison when he became prime minister in August 2018.

*

Internationally, Donald Trump seems to embody our very conflicting expectations and frustrations when it comes to leaders. We are as alarmed by the apparent powerlessness of American institutions to contain or direct him as we are by the erratic ignorance and nastiness of his actions. Yet a grudging respect sometimes sneaks into discussion of his...