- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

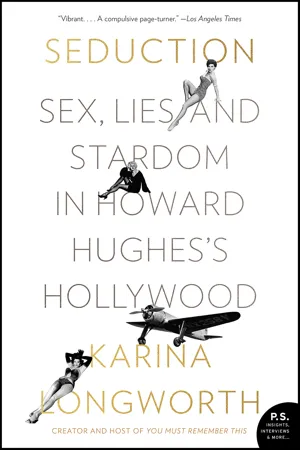

About this book

The host of the podcast

You Must Remember This explores Hollywood's golden age via the cinematic life of Howard Hughes and the women who encountered him.

Howard Hughes's reputation as a director and producer of films unusually defined by sex dovetails with his image as one of the most prolific womanizers of the twentieth century. The promoter of bombshell actresses such as Jean Harlow and Jane Russell, Hughes supposedly included among his off-screen conquests many of the most famous actresses of the era, among them Billie Dove, Katharine Hepburn, Ava Gardner, Ginger Rogers, and Lana Turner. Some of the women in Hughes's life were or became stars and others would stall out at a variety of points within the Hollywood hierarchy, but all found their professional lives marked by Hughes's presence.

In Seduction, Karina Longworth draws upon her own unparalleled expertise and an unpreceded trove of archival sources, diaries, and documents to produce a landmark—and wonderfully effervescent and gossipy—work of Hollywood history. It's the story of what it was like to be a woman in Hollywood during the industry's golden age, through the tales of actresses involved with Howard Hughes. This was the era not only of the actresses Hughes sought to dominate, but male stars such as Errol Flynn, Cary Grant, and Robert Mitchum; directors such as John Ford, Howard Hawks, and Preston Sturges; and studio chiefs like Irving Thalberg, Darryl Zanuck, and David O. Selznick—many of whom were complicit in the bedroom and boardroom exploitation that stifled and disappointed so many of the women who came to Los Angeles with hopes of celluloid triumph.

In his films, Howard Hughes commodified male desire more blatantly than any mainstream filmmaker of his time and in turn helped produce an incredibly influential, sexualized image of womanhood that has impacted American culture ever since. As a result, the story of him and the women he encountered is about not only the murkier shades of golden-age Hollywood, but also the ripples that still slither across today's entertainment industry and our culture in general.

Praise for Seduction

"Guaranteed to engross anyone with any interest at all in Hollywood, in movies, in #MeToo and in the never-ending story of men with power and women without." — New York Times Book Review

"The stories Longworth uncovers—about Katharine Hepburn and Jane Russell, yes, but also Ida Lupino and Faith Domergue and Anita Loos—are so rich, so compelling, that they urge you to question how much else in history has been lost within the swirling vortex of Great Men." — Atlantic

"A compelling and relevant must-read." — Entertainment Weekly

Howard Hughes's reputation as a director and producer of films unusually defined by sex dovetails with his image as one of the most prolific womanizers of the twentieth century. The promoter of bombshell actresses such as Jean Harlow and Jane Russell, Hughes supposedly included among his off-screen conquests many of the most famous actresses of the era, among them Billie Dove, Katharine Hepburn, Ava Gardner, Ginger Rogers, and Lana Turner. Some of the women in Hughes's life were or became stars and others would stall out at a variety of points within the Hollywood hierarchy, but all found their professional lives marked by Hughes's presence.

In Seduction, Karina Longworth draws upon her own unparalleled expertise and an unpreceded trove of archival sources, diaries, and documents to produce a landmark—and wonderfully effervescent and gossipy—work of Hollywood history. It's the story of what it was like to be a woman in Hollywood during the industry's golden age, through the tales of actresses involved with Howard Hughes. This was the era not only of the actresses Hughes sought to dominate, but male stars such as Errol Flynn, Cary Grant, and Robert Mitchum; directors such as John Ford, Howard Hawks, and Preston Sturges; and studio chiefs like Irving Thalberg, Darryl Zanuck, and David O. Selznick—many of whom were complicit in the bedroom and boardroom exploitation that stifled and disappointed so many of the women who came to Los Angeles with hopes of celluloid triumph.

In his films, Howard Hughes commodified male desire more blatantly than any mainstream filmmaker of his time and in turn helped produce an incredibly influential, sexualized image of womanhood that has impacted American culture ever since. As a result, the story of him and the women he encountered is about not only the murkier shades of golden-age Hollywood, but also the ripples that still slither across today's entertainment industry and our culture in general.

Praise for Seduction

"Guaranteed to engross anyone with any interest at all in Hollywood, in movies, in #MeToo and in the never-ending story of men with power and women without." — New York Times Book Review

"The stories Longworth uncovers—about Katharine Hepburn and Jane Russell, yes, but also Ida Lupino and Faith Domergue and Anita Loos—are so rich, so compelling, that they urge you to question how much else in history has been lost within the swirling vortex of Great Men." — Atlantic

"A compelling and relevant must-read." — Entertainment Weekly

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Seduction by Karina Longworth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film Direction & Production. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Hollywood Before Hell’s Angels, 1910–1928

Introduction

The Ambassador Hotel, 1925

It was like something out of a movie.

The Ambassador Hotel had opened, with much fanfare, in 1921, and had since become a nexus for power, money, and fame in a Los Angeles that was not yet the sole movie capital of the universe. Over the next few years, as the East Coast’s film industry dispersed west, the Ambassador, located eight miles due south of the Hollywood sign, would be a place where the fantasy worlds on-screen bled into real life. In the hotel’s nightclub, the Cocoanut Grove, tables were nestled and dancers nuzzled under an “actual” grove of papier-mâché palm trees, recycled from the set of a Rudolph Valentino movie—an ersatz tropics in the middle of a desert that had only recently been irrigated, and with great difficulty. With its Spanish-style main building surrounded by bungalows, and a floor plan that filled every room with sunlight and allowed for an unobstructed view straight through the building and fifteen miles out to the sea, the Ambassador had been intentionally designed as a testament to the utopian qualities of the West—both the real things that California actually offered, and the projected fantasies for which all that wide-open space provided a blank screen.

On this night in 1925, a group of powerful Hollywood producers and executives had gathered at the Ambassador for a celebratory dinner, and, for at least some of the men assembled, a handful of fantasies were about to come true. As servers brought out dessert, the sweets were accompanied by a selection of cheesecake. Frederica Sagor, a twenty-five-year-old secretary turned screenwriter whose adaptation of the 1924 college party novel The Plastic Age was about to turn a Brooklyn tomboy named Clara Bow into a major star, watched as a group of “starlets, nightclub belly dancers, and ladies of the evening” sauntered toward the dinner tables. The male dinner guests—many of them Sagor’s bosses—let out a drunken whoop, and soon each man was joined by a new friend. In groups of twos and threes, they began abandoning the dessert and disappearing together into bungalows.

Frederica was not surprised when her “date” for the evening, a sixty-something writer with whom she had been assigned by MGM to develop a feature called Flesh and the Devil for a twenty-year-old Swedish beauty named Greta Garbo, went AWOL with the rest of the men. She also wasn’t surprised when she saw her direct work supervisor, dimple-chinned Harry Rapf, among the “undressed, tousled men” who “chased naked women, shrieking with laughter.” And she wasn’t even all that surprised to see “immaculate” MGM boy wonder producer Irving Thalberg, who would soon marry the studio’s superstar Norma Shearer, “drunk, drunk, drunk.” She was surprised to see Antoinette—Frederica’s dressmaker, a French woman of about thirty who made reasonably priced copies of designer fashions—as one of the women hired for the evening’s entertainment.

Frederica would describe Antoinette as “gifted” and “hardworking”—meaning, in Sagor’s mind, the two women were alike. Neither of them was one of those girls, one of the thousands of chippies who came to town with nothing but their looks to recommend them, who had no qualms about doing whatever it took to stay afloat. Frederica had thought both she and Antoinette were earning their own livings on their own talents, neither of them having to sell her beauty or her body to do it. “Yet here she was,” Frederica marveled. “Antoinette, a call girl—half-naked, lying across a chair, her hand stretched out to receive the hundred-dollar bill being pressed into it by Eddie Mannix—gross, ugly, hairy, vulgar Eddie Mannix,* Louis B. Mayer’s bodyguard.”

The female body has always been a key building block of cinema—a raw material fed into the machine of the movies, as integral to the final product as celluloid itself. Few stories lay bare the imbalanced gender politics of this mechanized process, off-screen and off-set, as blatantly as Sagor’s tale of watching Antoinette at this party. But Frederica’s is also a story of persona, and perception. Here we have one woman who is struggling to sell something other than her body to Hollywood’s men, both eyewitnessing the debasement of a woman who she thought was like her, and also passing judgment on that woman for submitting to her own commodification. “I’d seen firsthand how Hollywood can bring you down if you allow it to do so, and I—unlike Antoinette and so many others—had enough basic self-respect not to let that happen to me,” Frederica declared. The unsaid realization in Sagor’s observation is that for Antoinette, being “gifted” and “hardworking” were not enough, that she also could only get something else that she wanted by becoming, or pretending to be, what men wanted her to be.

In this, she was like so many women integral to the rise of the movies, and to Hollywood’s ultimate domination of mid-twentieth-century popular culture: in an industry run by men and fueled by male desires, most women found they could find the most success by leaving something of their “real” selves behind. In exchange for the transformative boost of stardom, they allowed—not that it was always much of a choice—their bodies, personalities, backgrounds and/or names to be reinvented and sold. They took on personas, personas that, in some cases, so obscured who they had been that the kernel of truth behind the false front fell away.

If Howard Hughes was in attendance at this business dinner turned orgy, Sagor failed to notice him, but there was a reason why the Ambassador was the site nineteen-year-old Hughes chose around this time as the first home for him and his first bride, the former Ella Rice, upon moving to Los Angeles in 1925. The Texas millionaire—who in the years to come, between stints as a record-breaking aviator, a visionary inventor, and a harried defense contractor, would carry on an erratic career as a film producer—was naive about a lot of things when he arrived in Los Angeles, but the Ambassador wasn’t one of them. In fact, he probably knew the hotel better than any other single location in the city. His father, Howard Hughes Sr., had lived there for most of the last year of his own life, a time when he soothed the wounds of recent widowerhood with the excesses available to a man in Hollywood with money to spend. Howard’s uncle, the writer and director Rupert Hughes, had lived at the hotel with his own new (third) bride just a few months earlier.

The Ambassador had been the right place for one middle-aged Hughes man to enjoy the spoils of new bachelorhood, and for another middle-aged Hughes man to honeymoon with a woman less than half his age. The hotel, located about a mile due east from the bubbling crude of the La Brea Tar Pits, was also a logical launching pad for the youngest Hughes, whose inherited fortune was dependent on oil, and whose future would be a tapestry of movies, money, women, and blue-sky dreams. Indeed, it was the perfect set on which to begin staging a movie career during which—through the promotion of bombshells like Jean Harlow and Jane Russell and a consistent antagonism of censorship standards for on-screen titillation and movie marketing—he would aim to concentrate male desire into a commodity more blatantly than any mainstream filmmaker of his era.

Howard Hughes’s reputation as a filmmaker who was unusually obsessed with sex dovetails with his image as one of the most prolific playboys of the twentieth century. His supposed conquests between his first divorce in the late 1920s and his final marriage in 1957 included many of the most beautiful and famous women of the era, from silent star Billie Dove to the refined Katharine Hepburn to bombshells like Ava Gardner, Lana Turner, and Rita Hayworth to countless actresses who are today relatively obscure. For decades, gossip columns were full of items about the starlets he was supposedly on the verge of marrying.

How many of these stories were true? How many women did Howard Hughes really seduce? We will never know for sure, because, of all the fields he dabbled in, from aviation to corporations to entertainment, the area Howard Hughes truly mastered was publicity. “The romance stories were a lot of bologna,” posited Bill Feeder, a Variety reporter whom Hughes lured away to serve as director of RKO Public Relations in the 1950s. From the late 1920s through his acquisition of RKO Pictures in 1948, Hughes personally employed some of the most aggressive publicists in Hollywood in order to sell an image of Hughes as a genius scout of female talent. By the end of World War II, Hughes also had all the major gossip columnists and entertainment reporters of the era, including Hedda Hopper, Louella Parsons, and Sheilah Graham, in his pocket. These journalists were so dependent on Hughes (who knew all and saw all thanks to his blanketing of the movie colony with hired detectives and bribed eyes) for tips that they’d happily spin the stories he fed them to his liking. And, for all of his later secrecy and seclusion, during the peak of his Hollywood visibility Hughes showed an uncommon knack for getting photographed in the right place at the right time. “Hughes knew how much mileage he could get from being seen with the right woman,” remembered Feeder. “Sex and showmanship were the same thing to him.” Publicity was just another form of seduction.

One of the most written about but least-known famous men in Hollywood history, Hughes began playing a tug-of-war with the media shortly after arriving in Hollywood in 1925, using cooperative journalists to help him build a persona in which famous women would play a key role. Believed to be the heir to an oil fortune (in fact, Hughes had fully mortgaged his father’s company in order to seize sole ownership of drill bit manufacturer Hughes Tool), and perceived as a rube by the Hollywood elite, Hughes was a quick study when interested. With only a little experience he understood rapidly, and perhaps better than anyone else of his era, how to use publicity to project an image that could then become real—or, at least perceived to be real. Above all, Hughes understood how easily the gap between perception and reality could be made to disappear, and how to manipulate the blurred line to his advantage.

These skills served Hughes well during his rise and reign as a Hollywood iconoclast, through the release of spectacles like Hell’s Angels, Scarface, and The Outlaw, and a number of scandals and controversies. Then Hughes nearly died in a plane crash in 1946, and after that, much changed. His masterful ability to use the media to control the public’s perception of him slipped as he first became overextended as the owner and manager of RKO, and then began to slip away from a conventional public life, and conventional reality. After his disastrous stint as a studio chief ended in 1955, in January 1957 Hughes married actress Jean Peters, and shortly thereafter he began to hide out from all business and social obligations in screening rooms—and hotel rooms that, thanks to an army of assistants, were transformed into screening rooms. He’d spend much of the last decade of his life in bed, watching movies most of the time that he was awake. A failure as both an artist and a mogul, he became a full-time spectator.

By the end of Hughes’s life, when he was a codeine addict who spent his days and nights nodding in front of the TV, the former star aviator playboy would suddenly perk up when an actress he had once spent time with appeared on the screen. Hughes would allegedly call over one of his many aides, point, and say, “Remember her?” and then drift off into a grinning daydream of better days, days when his power to draw women to him and control not just their emotions but their movements, appearances, and identities was apparently limitless.

“NOT HALF A DOZEN men have ever been able to keep the whole equation of pictures in their heads,” F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote in the unfinished draft of what was to be his last novel, The Love of the Last Tycoon. He unwittingly set the template for the next seventy years of film writing with his next sentence: “And perhaps the closest a woman can come to the set-up is to try and understand one of those men.” But how to approach understanding Hollywood’s women, and their experiences of those men? As we move into an era in which there is frank public discussion of the exploitation, subjugation, manipulation, and abuse of women by men in positions of power, it’s time to rethink stories that lionize playboys, that celebrate the idea that women of the twentieth century were lands to be conquered, or collateral damage to a great man’s rise and fall. One way to begin that rethink is by exploring a playboy’s relationship with some of the women in his life from the perspective of those women.

This is a book about a few of the dozens of women who encountered Howard Hughes in Hollywood between the mid-1920s and early 1960s, whose lives and careers were impacted by their relationship with him. Some of these women were involved romantically with Hughes, others weren’t, but all found the course of their careers marked by his presence. Many are women whom Hughes manipulated, spied on, and even essentially kept prisoner—some of whom Hughes may not have had any sexual relationship with at all, and one of whom was his second wife. These were women whose faces and bodies Hughes strove to possess and/or make iconic, sometimes at an expense to their minds and souls. This is a book about the lives and work of women whose careers would stall out at a variety of points on the Hollywood totem pole, from never-known to canonical star to has-been, and it’s about where they were in those lives and careers when Hughes came along, where they ended up after he moved on from them, and the roles these women and Hughes played in the construction of one another’s public personae.

Mainly, it’s about what it was like to be a woman in Hollywood during what historians call the Classical Hollywood Era—roughly the mid-1920s through the end of the 1950s, the exact period of time Hughes was active in Hollywood. This period was marked by a number of evolutions and flash points, including the transition from silent film to sound; various sex and drug scandals that led to the institution of Hollywood’s self-censorship via the Production Code; the perfection of star-making through publicity practices that sometimes constituted more satisfying storytelling than the motion pictures themselves; the anti-Communist blacklisting of writers, directors, and stars; the government-mandated consent decree through which movie studios were forced to sell the movie theaters they owned in order to stay in production; and the decline of the star and studio systems in the wake of this monopoly-busting.

There are two important things to note about the events listed above. They all had an impact on the kinds of opportunities available for women in movies, on the screen and behind the scenes. And, Howard Hughes managed to have a hand in all of them.

Chapter 1

Hollywood Babylon

An orgy enjoyed by movie folk was the stuff of the worst nightmares of the original settlers of Hollywood. Places like the Ambassador became the sites of such casual debauchery in part because the neighborhood proper was so unwelcoming of it. Nestled into foothills and sprawling into wide, flat streets, the city of Hollywood grew slowly over the first decade of the twentieth century. The soon-to-be movie capital originally functioned as a hybrid suburban/rural village, with its population composed in large part of individualists: prohibitionists, suffragettes, retirees, and refugees from bleaker climes, all looking to cash in on the land. Independence came at a price, however, and by 1909, the city of Hollywood, population 10,000, was collapsing due to problems with sewage, drainage, and water. Unable to thrive on its own, the next year Hollywood was incorporated into the city of Los Angeles. By then a slow exodus had begun of film producers, directors, and performers from the East Coast to the West.

In keeping with its maverick spirit, the city of Hollywood had been resistant to the new fad. Man...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Cast of Characters

- Part I: Hollywood Before Hell’s Angels, 1910–1928

- Part II: Billie and Jean, 1928–1936

- Part III: Hepburn and Rogers and Russell, 1932–1940

- Part IV: Life During Wartime, 1941–1946

- Part V: Terry, Jean, and RKO, 1948–1956

- Part VI: Hughes After RKO

- Epilogue: Life After Death

- Notes on Sources and Acknowledgments

- Bibliography

- Filmography

- Notes

- Index

- Photo Section

- P.S. Insights, Interviews & More . . .*

- Praise

- Copyright

- About the Publisher