1

The Dawn of the Dinosaurs

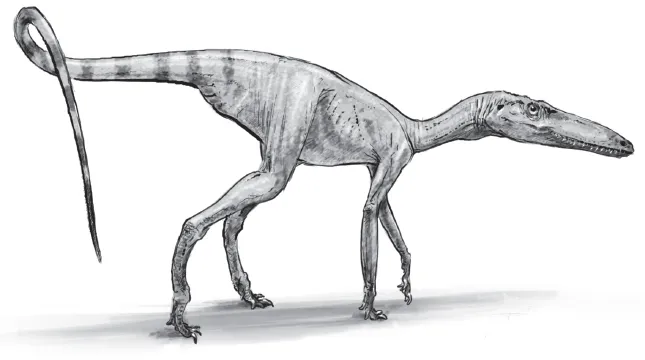

Prorotodactylus

Chapter Title art by Todd Marshall

“BINGO,” MY FRIEND GRZEGORZ NIEDŹWIEDZKI shouted, pointing at a knife-thin separation between a slim strip of mudstone and a thicker layer of coarser rock right above it. The quarry we were exploring, near the tiny Polish village of Zachełmie, was once a source of sought-after limestone but had long been abandoned. The surrounding landscape was littered with decaying smokestacks and other remnants of central Poland’s industrial past. The maps deceitfully told us we were in the Holy Cross Mountains, a sad patch of hills once grand but now nearly flattened by hundreds of millions of years of erosion. The sky was gray, the mosquitoes were biting, heat was bouncing off the quarry floor, and the only other people we saw were a couple of wayward hikers who must have made a tragically wrong turn.

“This is the extinction,” Grzegorz said, a big smile creasing the unshaven stubble of many days of fieldwork. “Many footprints of big reptiles and mammal cousins below, but then they disappear. And above, we see nothing for awhile, and then dinosaurs.”

We may have been peering at some rocks in an overgrown quarry, but what we were really looking at was a revolution. Rocks record history; they tell stories of deep ancient pasts long before humans walked the Earth. And the narrative in front of us, written in stone, was a shocker. That switch in the rocks, detectable perhaps only to the overtrained eyes of a scientist, documents one of the most dramatic moments in Earth history. A brief instance when the world changed, a turning point that happened some 252 million years ago, before us, before woolly mammoths, before the dinosaurs, but one that still reverberates today. If things had unfolded a little differently back then, who knows what the modern world would be like? It’s like wondering what might have happened if the archduke was never shot.

IF WE’D BEEN standing in this same spot 252 million years ago, during a slice of time geologists call the Permian Period, our surroundings would have been barely recognizable. No ruined factories or other signs of people. No birds in the sky or mice scurrying at our feet, no flowery shrubs to scratch us up or mosquitoes to feed on our cuts. All of those things would evolve later. We still would have been sweating, though, because it was hot and unbearably humid, probably more insufferable than Miami in the middle of the summer. Raging rivers would’ve been draining the Holy Cross Mountains, which were actually proper mountains back then, with sharp snowy peaks jutting tens of thousands of feet into the clouds. The rivers wound their way through vast forests of conifer trees—early relatives of today’s pines and junipers—emptying into a big basin flanking the hills, dotted with lakes that swelled in the rainy season but dried out when the monsoons ended.

These lakes were the lifeblood of the local ecosystem, watering holes that provided an oasis from the harsh heat and wind. All sorts of animals flocked to them, but they weren’t animals we would know. There were slimy salamanders bigger than dogs, loitering near the water’s edge and occasionally snapping at a passing fish. Stocky beasts called pareiasaurs waddled around on all fours, their knobby skin, front-heavy build, and general brutish appearance making them seem like a mad reptilian offensive lineman. Fat little things called dicynodonts rummaged around in the muck like pigs, using their sharp tusks to pry up tasty roots. Lording over it all were the gorgonopsians, bear-size monsters who reigned at the top of the food chain, slicing into pareiasaur guts and dicynodont flesh with their saberlike canines. This cast of oddballs ruled the world right before the dinosaurs.

Then, deep inside, the Earth began to rumble. You wouldn’t have been able to feel it on the surface, at least when it kicked off, right around 252 million years ago. It was happening fifty, maybe even a hundred, miles underground, in the mantle, the middle layer of the crust-mantle-core sandwich of Earth’s structure. The mantle is solid rock that is so hot and under such intense pressure that, over long stretches of geological time, it can flow like extra-viscous Silly Putty. In fact, the mantle has currents just like a river. These currents are what drive the conveyor-belt system of plate tectonics, the forces that break the thin outer crust into plates that move relative to each other over time. We wouldn’t have mountains or oceans or a habitable surface without the mantle currents. However, every once in a while, one of the currents goes rogue. Hot plumes of liquid rock break free and start snaking their way upward to the surface, eventually bursting out through volcanoes. These are called hot spots. They’re rare, but Yellowstone is an example of an active one today. The constant supply of heat from the deep Earth is what powers Old Faithful and the other geysers.

This same thing was happening at the end of the Permian Period, but on a continent-wide scale. A massive hot spot began to form under Siberia. The streams of liquid rock rushed through the mantle into the crust and flooded out from volcanoes. These weren’t ordinary volcanoes like the ones we’re most used to, the cone-shaped mounds that sit dormant for decades and then occasionally explode with a bunch of ash and lava, like Mount Saint Helens or Pinatubo. They wouldn’t have erupted with the vigor of those vinegar-and-baking-soda contraptions so many of us made as science fair experiments. No, these volcanoes were nothing more than big cracks in the ground, often miles long, that continuously belched out lava, year after year, decade after decade, century after century. The eruptions at the end of the Permian lasted for a few hundred thousand years, perhaps even a few million. There were a few bigger eruptive bursts and quieter periods of slower flow. All in all, they expelled enough lava to drown several million square miles of northern and central Asia. Even today, more than a quarter billion years later, the black basalt rocks that hardened out of this lava cover nearly a million square miles of Siberia, about the same land area as Western Europe.

Imagine a continent scorched with lava. It’s the apocalyptic disaster of a bad B movie. Suffice it to say, all of the pareiasaurs, dicynodonts, and gorgonopsians living anywhere near the Siberian area code were finished. But it was worse than that. When volcanoes erupt, they don’t expel only lava, but also heat, dust, and noxious gases. Unlike lava, these can affect the entire planet. At the end of the Permian, these were the real agents of doom, and they started a cascade of destruction that would last for millions of years and irrevocably change the world in the process.

Dust shot into the atmosphere, contaminating the high-altitude air currents and spreading around the world, blocking out the sun and preventing plants from photosynthesizing. The once lush conifer forests died out; then the pareiasaurs and dicynodonts had no plants to eat, and then the gorgonopsians had no meat. Food chains started to collapse. Some of the dust fell back through the atmosphere and combined with water droplets to form acid rain, which exacerbated the worsening situation on the ground. As more plants died, the landscape became barren and unstable, leading to massive erosion as mudslides wiped out entire tracts of rotting forest. This is why the fine mudstones in the Zachełmie quarry, a rock type indicative of calm and peaceful environments, suddenly gave way to the coarser boulder-strewn rocks so characteristic of fast-moving currents and corrosive storms. Wildfires raged across the scarred land, making it even more difficult for plants and animals to survive.

But those were just the short-term effects, the things that happened within the days, weeks, and months after a particularly large burst of lava spilled through the Siberian fissures. The longer-term effects were even more deadly. Stifling clouds of carbon dioxide were released with the lava. As we know all too well today, carbon dioxide is a potent greenhouse gas, which absorbs radiation in the atmosphere and beams it back down to the surface, warming up the Earth. The CO2 spewed out by the Siberian eruptions didn’t raise the thermostat by just a few degrees; it caused a runaway greenhouse effect that boiled the planet. But there were other consequences as well. Although a lot of the carbon dioxide went into the atmosphere, much of it also dissolved into the ocean. This causes a chain of chemical reactions that makes the ocean water more acidic, a bad thing, particularly for those sea creatures with easily dissolvable shells. It’s why we don’t bathe in vinegar. This chain reaction also draws much of the oxygen out of the oceans, another serious problem for anything living in or around water.

Descriptions of the doom and gloom could go on for pages, but the point is, the end of the Permian was a very bad time to be alive. It was the biggest episode of mass death in the history of our planet. Somewhere around 90 percent of all species disappeared. Paleontologists have a special term for an event like this, when huge numbers of plants and animals die out all around the world in a short time: a mass extinction. There have been five particularly severe mass extinctions over the past 500 million years. The one 66 million years ago at the end of the Cretaceous period, which wiped out the dinosaurs, is surely the most famous. We’ll get to that one later. As horrible as the end-Cretaceous extinction was, it had nothing on the one at the end of the Permian. That moment of time 252 million years ago, chronicled in the swift change from mudstone to pebbly rock in the Polish quarry, was the closest that life ever came to being completely obliterated.

Then things got better. They always do. Life is resilient, and some species are always able to make it through even the worst catastrophes. The volcanoes erupted for a few million years, and then they stopped as the hot spot lost steam. No longer blighted by lava, dust, and carbon dioxide, ecosystems were gradually able to stabilize. Plants began to grow again, and they diversified. They provided new food for herbivores, which provided meat for carnivores. Food webs reestablished themselves. It took at least five million years for this recovery to unfold, and when it did, things were better but now very different. The previously dominant gorgonopsians, pareiasaurs, and their kin were never to stalk the lakesides of Poland or anywhere else while the plucky survivors had the whole Earth to themselves. A largely empty world, an uncolonized frontier. The Permian had transitioned into the next interval of geological time, the Triassic, and things would never be the same. Dinosaurs were about to make their entrance.

AS A YOUNG paleontologist, I yearned to understand exactly how the world changed as a result of the end-Permian extinction. What died and what survived, and why? How quickly did ecosystems recover? What new types of never-before-imagined creatures emerged from the post-apocalyptic blackness? What aspects of our modern world were first forged in the Permian lavas?

There’s only one way to start answering these questions. You need to go out and find fossils. If a murder has been committed, a detective begins by studying the body and the crime scene, looking for fingerprints, hair, clothing fibers, or other clues that might tell the story of what unfolded, and lead to the culprit. For paleontologists, our clues are fossils. They are the currency of our field, the only records of how long-extinct organisms lived and evolved.

Fossils are any sign of ancient life, and they come in many forms. The most familiar are bones, teeth, and shells—the hard parts that form the skeleton of an animal. After being buried in sand or mud, these hard bits are gradually replaced by minerals and turned to rock, leaving a fossil. Sometimes soft things like leaves and bacteria can fossilize as well, often by making impressions in the rock. The same is sometimes true of the soft parts of animals, like skin, feathers, or even muscles and internal organs. But to end up with these as fossils, we need to be very lucky: the animal needs to be buried so quickly that these fragile tissues don’t have time to decay or get eaten by predators.

Everything I describe above is what we call a body fossil, an actual part of a plant or animal that turns into stone. But there is another type: a trace fossil, which records the presence or behavior of an organism or preserves something that an organism produced. The best example is a footprint; others are burrows, bite marks, coprolites (fossilized dung), and eggs and nests. These can be particularly valuable, because they can tell us how extinct animals interacted with each other and their environment—how they moved, what they ate, where they lived, and how they reproduced.

The fossils that I’m particularly interested in belong to dinosaurs and the animals that came immediately before them. Dinosaurs lived during three periods of geological history: the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous (which collectively form the Mesozoic Era). The Permian Period—when that weird and wonderful cast of creatures was frolicking alongside the Polish lakes—came right before the Triassic. We often think of the dinosaurs as ancient, but in fact, they’re relative newcomers in the history of life.

The Earth formed about 4.5 billion years ago, and the first microscopic bacteria evolved a few hundred million years later. For some 2 billion years, it was a bacterial world. There were no plants or animals, nothing that could easily be seen by the naked eye, had we been around. Then, some time around 1.8 billion years ago, these simple cells developed the ability to group together into larger, more complex organisms. A global ice age...