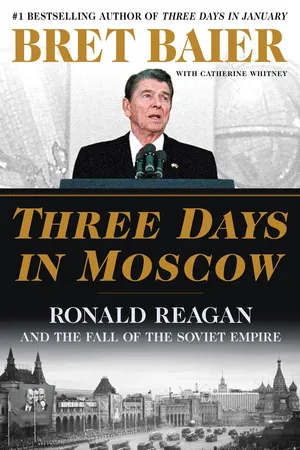

Three Days in Moscow

Ronald Reagan and the Fall of the Soviet Empire

- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

"An instant classic, if not the finest book to date on Ronald Reagan.” — Jay Winik

President Reagan's dramatic battle to win the Cold War is revealed as never before by the #1 bestselling author and award-winning anchor of the #1 rated Special Report with Bret Baier.

Moscow, 1988: 1,000 miles behind the Iron Curtain, Ronald Reagan stood for freedom and confronted the Soviet empire.

In his acclaimed bestseller Three Days in January, Bret Baier illuminated the extraordinary leadership of President Dwight Eisenhower at the dawn of the Cold War. Now in his highly anticipated new history, Three Days in Moscow, Baier explores the dramatic endgame of America’s long struggle with the Soviet Union and President Ronald Reagan’s central role in shaping the world we live in today.

On May 31, 1988, Reagan stood on Russian soil and addressed a packed audience at Moscow State University, delivering a remarkable—yet now largely forgotten—speech that capped his first visit to the Soviet capital. This fourth in a series of summits between Reagan and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev, was a dramatic coda to their tireless efforts to reduce the nuclear threat. More than that, Reagan viewed it as “a grand historical moment”: an opportunity to light a path for the Soviet people—toward freedom, human rights, and a future he told them they could embrace if they chose. It was the first time an American president had given an address about human rights on Russian soil. Reagan had once called the Soviet Union an “evil empire.” Now, saying that depiction was from “another time,” he beckoned the Soviets to join him in a new vision of the future. The importance of Reagan’s Moscow speech was largely overlooked at the time, but the new world he spoke of was fast approaching; the following year, in November 1989, the Berlin Wall fell and the Soviet Union began to disintegrate, leaving the United States the sole superpower on the world stage.

Today, the end of the Cold War is perhaps the defining historical moment of the past half century, and must be understood if we are to make sense of America’s current place in the world, amid the re-emergence of US-Russian tensions during Vladimir Putin’s tenure. Using Reagan’s three days in Moscow to tell the larger story of the president’s critical and often misunderstood role in orchestrating a successful, peaceful ending to the Cold War, Baier illuminates the character of one of our nation’s most venerated leaders—and reveals the unique qualities that allowed him to succeed in forming an alliance for peace with the Soviet Union, when his predecessors had fallen short.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction: Finding Reagan

- Prologue: The Walk

- Part One: Reagan’s Destiny

- Part Two: Speaking Truth

- Part Three: Three Days in Moscow

- Part Four: Dreams for the Future

- The Last Word: 2018

- Acknowledgments

- Appendix: Ronald Reagan’s Speech at Moscow State University

- Notes

- Index

- Photo Section

- About the Author

- Praise for Three Days in Moscow

- Also by Bret Baier

- Copyright

- About the Publisher