- 480 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

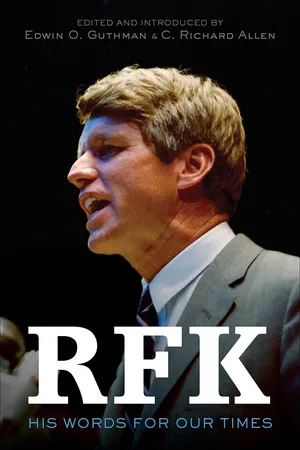

An inspiring collection of Robert Francis Kennedy's most famous speeches accompanied by commentary from notable historians and public figures.

Twenty-five years after Bobby Kennedy was assassinated, RFK: His Words for Our Times, a celebration of Kennedy's life and legacy, was published to enormous acclaim. Now this classic volume has been thoroughly edited and updated. Through his own words we get a direct and intimate perspective on Kennedy's views on civil rights, social justice, the war in Vietnam, foreign policy, the desirability of peace, the need to eliminate poverty, and the role of hope in American politics.

Here, too, is evidence of the impact of those he knew and worked with, including his brother John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Cesar Chavez, among others. The tightly curated collection also includes commentary about RFK's legacy from major historians and public figures, among them Barack Obama, Bill Clinton, Eric Garcetti, William Manchester, Elie Wiesel, and Desmond Tutu. Assembled with the full cooperation of the Kennedy family, RFK: His Words for Our Times is a potent reminder of Robert Kennedy's ability to imagine a greater America—a faith and vision we could use today.

"Themes include civil rights, mistrust of large government, citizen participation in local government, eliminating poverty, and ending the Vietnam War. The speeches demonstrate Kennedy's skill at connecting with large, enthusiastic audiences with promises of hope and equality." — Library Journal

"A blueprint for the future." — Vital Speeches

Twenty-five years after Bobby Kennedy was assassinated, RFK: His Words for Our Times, a celebration of Kennedy's life and legacy, was published to enormous acclaim. Now this classic volume has been thoroughly edited and updated. Through his own words we get a direct and intimate perspective on Kennedy's views on civil rights, social justice, the war in Vietnam, foreign policy, the desirability of peace, the need to eliminate poverty, and the role of hope in American politics.

Here, too, is evidence of the impact of those he knew and worked with, including his brother John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Cesar Chavez, among others. The tightly curated collection also includes commentary about RFK's legacy from major historians and public figures, among them Barack Obama, Bill Clinton, Eric Garcetti, William Manchester, Elie Wiesel, and Desmond Tutu. Assembled with the full cooperation of the Kennedy family, RFK: His Words for Our Times is a potent reminder of Robert Kennedy's ability to imagine a greater America—a faith and vision we could use today.

"Themes include civil rights, mistrust of large government, citizen participation in local government, eliminating poverty, and ending the Vietnam War. The speeches demonstrate Kennedy's skill at connecting with large, enthusiastic audiences with promises of hope and equality." — Library Journal

"A blueprint for the future." — Vital Speeches

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access RFK by Robert F. Kennedy, Edwin O. Guthman,C. Richard Allen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literatura & Biografías políticas. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Journalist, Senate Committee Counsel, Campaign Manager

1948–1960

The Early Years: Out of Harvard

KENNEDY STEPPED INTO THE PUBLIC ARENA shortly after completing his undergraduate studies at Harvard in 1948, not as a public official or politician but as a journalist. His reporting provides the clearest insight into his thought processes before October 10, 1955, when he gave his first formal speech—a report on his trip with U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas to Soviet Central Asia and Siberia. On March 5, 1948, he sailed on the Queen Mary bound for Europe and the Middle East armed with press credentials that his father, Joseph P. Kennedy, had secured for him from the Boston Post. He was twenty-two years old. After spending several days in London and then Cairo, Kennedy landed in Tel Aviv on March 26—amid violence, intrigue, and intense hostility. The British mandate to rule Palestine, which derived from the old League of Nations, was due to end on May 14, because the previous November the fledgling United Nations General Assembly had decided to partition the ancient land into the two states of Israel and Palestine. As the British prepared to withdraw, Arabs and Jews were fighting fiercely throughout Palestine while the United Nations Security Council dithered over how or whether to enforce partition. Kennedy reached Jerusalem in an armored car, visited a kibbutz, and interviewed people on both sides of the conflict, including soldiers of the Haganah (the Jewish paramilitary force) and right-wing Irgun Zvai Leumi guerrillas, whose violent forays against the British and Arabs had left scores dead. In early April he went to Lebanon, and then he continued through Istanbul and Athens to Rome. On May 14, as the British mandate ended, the Jews promptly proclaimed the new state of Israel with borders conforming to the United Nations partition plan. President Harry Truman formally granted diplomatic recognition, and the next day the armies of Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon invaded, touching off the first Arab-Israeli War. It would end fourteen months later with the invaders defeated.

Although Kennedy wrote his pieces in April, before the May declaration of Israeli independence, the Boston Post published them on four successive days, beginning on June 3 when a photograph of Robert Kennedy appeared on the front page alongside a story that carried a two-column headline: “British Hated by Both Sides.” An italicized introduction informed readers that the article was “the first of a special series on the Palestine situation written by Robert Kennedy,” and noted “Young Kennedy has been traveling through the Middle East and his first-hand observations, appearing exclusively in the Post, will be of considerable interest in view of the current crisis.”

Kennedy began his report by observing that Arthur Balfour, England’s foreign secretary during the latter half of World War I, would have made his declaration (calling for a homeland for the Jews in Palestine) clearer if he could have foreseen how much bloodshed its ambiguity was causing. “No great thought,” Kennedy wrote, “was given it at the time, for Palestine was then a relatively unimportant country. There were then not the great numbers of homeless Jews and no one believed then that the permission granted for Jewish immigration would lead 30 years later to world turmoil on whether a national home should mean an autonomous national state.” Then he impartially outlined the positions of the Jews and the Arabs, asserting that “it is an unfortunate fact that because there are such well-founded arguments on either side each grows more bitter toward the other. Confidence in their right increases in direct proportion to the hatred and mistrust for the other side for not acknowledging it.”

A second article detailed Kennedy’s encounters with security forces and ordinary Jews, and described his visit to a kibbutz. He understood that the eight hundred thousand Jews, many of them refugees from Europe, had no place else to go. “They can go into the Mediterranean Sea and get drowned,” he wrote, “or they can stay and fight and perhaps get killed. They will fight and they will fight with unparalleled courage. This is their greatest and last chance. The eyes of the world are upon them and there can be no turning back.”

He continued: “Their shortages in arms and numbers are more than compensated by an undying spirit that the Arabs, Iraqis, Syrians, Lebanese, Saudi Arabians, Egyptians, and those from Trans-Jordan can never have. They are a young, tough, determined nation and will fight as such.”

Kennedy’s third article began with a statement that there was no chance to avoid war between the Jews and the Arabs when the British left (as had in fact happened between the time the piece was written and when it was published), and opined that the sooner the British departed, the better for the Jews because the British opposed the Jewish cause and were aiding the Arabs. Then, midway through the article, he wrote that he was becoming

more and more conscious of the great heritage to which we as United States citizens are heirs and which we have a duty to preserve. A force motivating my writing this paper is that I believe we have failed in this duty or are in great jeopardy of doing so . . .

Our government first decided that justice was on the Jewish side in their desire for a homeland and then it reversed its decision temporarily. Because of this action I believe we have burdened ourselves with a great responsibility in our own eyes and in the eyes of the world. We fail to live up to that responsibility if we knowingly support the British government who behind the skirts of their official position attempt to crush a cause with which they are not in accord. If the American people knew the true facts, I am certain a more honest and forthright policy would be substituted for the benefit of all.

In the final article, Kennedy predicted that “before too long” the United States and Great Britain would be looking to a Jewish state to preserve “a toehold” for democracy in the Middle East. Some diplomats in Washington and other Western capitals were concerned that Soviet intrigue and intervention might succeed in turning the new Jewish nation into a Communist satellite. Kennedy rejected that concern out of hand:

That the people might accept Communism or that Communism could exist in Palestine is fantastically absurd. Communism thrives on static discontent as sin thrives on idleness. With the type of issues and people involved, that state of affairs is nonexistent. I am as certain of that as of my name . . . Communism demands allegiance to the mother country, Russia, and it is impossible to believe that people would undergo such untold suffering to replace one tyrant with another.

The four articles not only marked his entry into the arena of public affairs but also foretold what kind of an observer and writer he would be: strong-minded, specific, and perceptive. At a time when leading diplomats in America and around the world doubted a Jewish state was needed or could survive, he wrote that the Jews would win the war and establish “a truly great modern example of the birth of a nation in dignity and self-respect.” He did not anticipate that similar yearnings among Palestinians would remain unsatisfied seven decades after his visit.

Lecture on Soviet Central Asia

Georgetown University; Washington, D.C.

October 10, 1955

IN 1950, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Douglas was planning a trip to five Soviet Central Asian Republics—Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tadzhikistan, Kirghizia, and Kazakhstan—and at Joseph Kennedy’s request, he agreed to take Robert along. The elder Kennedy and Douglas, though poles apart politically, had remained close friends since 1934 when Kennedy, then chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, recruited Douglas, then a Yale Law School professor, to join the SEC staff. Douglas and Robert Kennedy applied for visas in January 1951. It was near the end of Joseph Stalin’s malevolent regime. Their applications were acknowledged, but visas were not issued.

Kennedy served briefly in the Internal Security Division of the Department of Justice, which prosecuted espionage and subversive-activity cases. He transferred to the Criminal Division and was working on a corruption investigation in New York when he resigned in 1952 to manage his brother John’s senatorial campaign that, despite the Eisenhower landslide, unseated the Republican incumbent, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. In January 1953, Kennedy joined the staff of the Senate Government Operations Committee’s Investigations Subcommittee; at the same time, the highly controversial, Red-hunting Senator Joseph R. McCarthy of Wisconsin, as ranking Republican and Kennedy family friend, was taking over as the subcommittee’s chairman. Kennedy helped investigate trade between Communist China and Western Allies while American and other allied soldiers fought under the United Nations flag against Chinese troops in Korea. In May he testified before the subcommittee that two British-owned ships, flying Panamanian flags, had transported Chinese troops.

A month later, Kennedy resigned in protest and dismay over McCarthy’s heavy-handed tactics (and an intense dislike of his chief counsel, Roy Cohn). The next year he returned to the subcommittee as counsel to the Democratic minority that opposed McCarthy, and he became the subcommittee’s chief counsel in 1955 after the Democrats regained control of the Senate in the 1954 election.

Douglas and Kennedy, after their visa applications to visit Soviet Central Asia were not granted in 1951, applied every year without success until January 1955. Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet Union’s leader since Joseph Stalin’s death almost two years earlier, was edging toward a summit conference with President Eisenhower and, perhaps as a measure of good will, visa applications were approved within a week. That summer, Kennedy—taking leave from the Senate Investigations Subcommittee and paying his own way—and Douglas spent six weeks touring the five Central Asian republics where in many areas no Americans had been allowed since the Russian Revolution. Then they made a brief detour into Siberia before meeting Kennedy’s wife, Ethel, and his sisters Jean and Pat in Moscow.

He returned very distrustful that the post-Stalin era would result in real change regarding United States–Soviet relations, though he felt Communism had raised the people’s standard of living. He wrote a report on his travels, which he read at Georgetown University, accompanied by slides of his photographs from the trip. It was his maiden public speech.

***

In relation to its size and the antiquity of its history, the West knows less of Soviet Central Asia than any part of the civilized world. Its size of over one and a half million square miles makes it an area larger than India before partition and bigger than all of Western Europe. Its population of approximately 18 million is larger than the populations of either Canada or Australia. The two cities of Samarkand and Bukhara rival Baghdad and Damascus in cultural and religious history. For a long period of time the city of Bukhara in Uzbekistan was the center of Muslim religious fanaticism, even more so than any place in the Middle East. Yet, despite these facts and this background, we know far more about the cities and countries surrounding Soviet Central Asia than we do about this area itself. Our knowledge of Persia, Afghanistan, and even Tibet is vast compared to the information we have about Kasakhstan or Kirghizia. In fact, I doubt that there are many people in the United States who have even heard of them.

This area which was traveled and established as a main trading route by Marco Polo, overrun and conquered by Alexander the Great and Genghis Khan, and controlled by Tamerlane, has had only a handful of visitors since the turn of the sixteenth century. This was due partially to its remoteness, which became more acute when the Portuguese rounded the Cape of Good Hope and the route to Asia became a sea route rather than land, and partially to the fact that visitors were just not welcome by the local inhabitants. The first visitors to the city of Bukhara, other than a handful of envoys who came down from Russia, were two Englishmen, Stoddard and Connolly. In 1841 they visited the emir of Bukhara, the local leader of that area, in order to help him train his army to fight against the Russians. The emir, being rather distrustful of foreigners, chained them to the floor of what was aptly called the Bug Pit. After two months the emir took them out and asked them to acknowledge the Muslim religion as the only true religion. By that time they had developed a dislike of the emir and refused, whereupon he beheaded them. From personal experience I know the bugs were not the only difficulty with which Stoddard and Connolly had to contend. When Justice Douglas and I visited the Bug Pit in Bukhara last summer, the temperature read 145 degrees Fahrenheit.

The Russians began their conquest of Central Asia in the 1860s. However, some of the cities such as Bukhara remained under local control until they were taken over by the Soviets during the early 1920s and the local emirs deposed. In fact, some of the members of the harem of the emir of Bukhara are still alive.

During the Russian advance into this whole area, very few outside visitors were allowed. When the Communists took over in the 1920s, the veil of isolation hardened and for a long period it has been specifically closed to Americans. We were visiting an area of the world which, if for no other reason, was made unique by its remoteness . . .

We were interested in knowing what it was that made this colonialism acceptable to the Russians when the stated Soviet policy is against colonialism of any kind.

An added reason for us wanting to visit that part of the world was that Soviet Central Asia, prior to Communist control, had been an intensely religious area. In Bukhara alone over three hundred mosques and religious schools had flourished. How had the Muslim religion fared in the face of Communist teachings that there is no God and that religion is for the backward people?

I left Washington on the twenty-seventh of July, after stocking up on pills for stomach trouble and infection and others to purify the drinking water . . . On the first of August we took a ship from Pahlevi in Iran to Baku, the Russian oil city. We were the first Americans to take this trip on the Caspian Sea . . .

We were told before we left the U.S.A. that we must expect that all our hotel rooms in Russia would have listening devices in them and that we should govern our conversations accordingly. When we arrived in Baku we found nobody was prepared for us. No arrangements had been made to procure a guide and interpreter for us on our trip. The representative of ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Kennedy as Writer and Speaker

- Introduction

- Robert Kennedy’s Legacy Featuring Essays by

- Garry Wills

- Part Two: Mr. Attorney General (January 20, 1961–September 3, 1964)

- Part Three: The Senate Years (1965–1968)

- Part Four: The 1968 Presidential Campaign

- Acknowledgments

- Appendix: Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights

- Chronology: Robert Francis Kennedy

- Notes

- Sources

- Index

- Photo Section

- About the Authors

- Copyright

- About the Publisher