Chapter 1

Tenacity

What it is, and why it matters

Let me tell you the secret that has led me to my goal. My strength lies solely in my tenacity.

Louis Pasteur

Teachers join the profession with high hopes for the impact they might have on students. They know that a good number of students will need to be enthused about their particular subject, or even about being in school in general. For a teacher, witnessing a ‘light bulb moment’ – when hard thinking, doing and trying pays off and a student ‘gets it’ for the first time – is hugely rewarding. These moments are precious because they are both the result of tenacity and its reward. The more of these moments students experience, the more they will associate persevering with success and hard work with a feeling of elation.

Tenacity is a broad concept encompassing a range of dispositions promoting learning and achievement in and beyond school. Carol Dweck and colleagues (2014) describe one powerful element, ‘academic tenacity’, in a report for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Academic tenacity, the authors suggest, is a collection of ‘non-cognitive factors that promote long-term learning and achievement’. It is about ‘the mindsets and skills that allow students to: look beyond short-term concerns to longer-term or higher-order goals, and withstand challenges and setbacks to persevere toward these goals’ (p. 4).

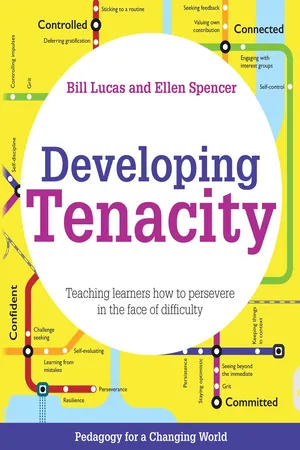

This is a very helpful starting point. But we will want to go beyond the ‘academic’ in this book. Tenacity, we will suggest, is made up of a number of overlapping concepts: resilience, persistence, perseverance, grit and self-control. Here we begin to look at each concept, what it contributes and why each is not enough on its own.

Resilience

The Latin root of resilience, resilire, means to ‘jump back’ or ‘recoil’. It describes the property of elastic material to absorb energy and spring back to its original shape upon release. In human terms, it has typically referred to a person’s mental ability to recover quickly from illness, disadvantage or misfortune. It is now commonly used as a subset of a larger concept – perseverance. Resilient people can bounce back from failure, misfortune, shock or illness. Resilience has both a mental component relating to attitude and decision-making and a physical one to do with behaviour (Kyriacou, 2016, p. 39). Such bouncebackability is a kind of mental toughness.

Resilience is not a fixed personality trait but a learnable competence (Meredith et al., 2011, p. 3). Meredith and colleagues found 122 definitions of resilience ranging from basic (a relatively simple process or capacity that can be developed), to adaptation (including the concept of ‘bouncing back’, adapting or returning to a baseline after experiencing adversity or trauma), to ‘growth’ (following adversity, for example). The authors choose to define resilience as the capacity to adapt successfully in the presence of risk and adversity.

Persistence

Persistence is being able to stick with a specific task in the face of difficulty, challenge, opposition or failure. It is a characteristic of successful learners in academic disciplines and in life. It implies a single-mindedness of effort when dealing with a specific activity. Along with a willingness to deploy effort, persistence is a core aspect of a student’s engagement in learning. Indeed, the combination of effort and persistence has been shown to increase achievement (Miller et al., 1996), as well as being useful life skills in their own right.

Perseverance

Perseverance, although frequently used as a synonym for persistence, is stronger, implying continuing effort over time. Someone who perseveres may do so in the face of discouragement, opposition or past failure. They behave ‘in an engaged, focused, and persistent manner in pursuit of academic goals, despite obstacles, setbacks, and distractions’ (Farrington et al., 2012, p. 20). The terms ‘persistence’ and ‘resilience’ can, arguably, be subsumed within this label. Students’ perseverance can vary depending on the circumstances. One task may engender perseverance while another may demotivate. There is a wealth of evidence showing that perseverance is malleable (Farrington et al., 2012, p. 24), although the degree to which this is possible ‘lies on a spectrum’ (Heckman and Kautz, 2013, p. 10).

Camille Farrington argues that academic perseverance is highly learnable because it applies to the specific context of persevering at academic tasks, so ‘students can be influenced to demonstrate perseverant behaviors – such as persisting at academic tasks, seeing big projects through to completion, and buckling down when schoolwork gets hard – in response to certain classroom contexts and under particular psychological conditions’ (Farrington et al., 2012, p. 24).

For some tasks in school, and in life, a specific kind of perseverance is called for – academic diligence. This is defined as ‘working assiduously on academic tasks which are beneficial in the long-run but tedious in the moment’ (Galla et al., 2014, p. 315).

Grit

Grit, brought to popular attention by Angela Duckworth, is a combination of both perseverance and passion for long-term goals (or ‘consistency of interest’: Duckworth et al., 2007). It has generated much coverage in the media, to the point that even its ‘creator’ urges caution in an article that warns against the way ‘the enthusiasm has rapidly outpaced the science’ (Dahl, 2016).

In fact, the idea of grit pre-dates contemporary thinkers by some 200 years, being widely used in North American slang in the sense of having ‘pluck’ or ‘firmness of mind’. It has Anglo-Saxon roots, too, in its literal meaning of a particle of crushed rock. We like the idea of grit precisely because it is so embedded in the English language as a common-sense idea. Like ‘gumption’ and ‘nous’, it brings with it a history of useful application and widespread acceptance.

Grit relates to ‘deliberate practice’, reflecting on failures, self-regulation and metacognition. It is also associated with Carol Dweck’s idea of a growth mindset (Hinton and Hendrick, 2015, p. 4). Duckworth defines grit as:

Grit relates closely to tenacity, but for reasons predominantly related to the limited learnability of grit, there are a number of reasons why we have chosen to use the latter concept to develop a framework that might be of practical use to teachers.

First, grit incorporates the element of passion, which is not a learnable habit or mental disposition. In terms of Duckworth’s Grit Scale, low overall scores are often caused by low passion scores. While people can learn to appreciate their circumstances better or to be thankful for what they have, passion goes beyond contentment and is not a capability that is likely to be as responsive to teaching interventions in the way that, say, self-control might be. While there is plenty of focus on developing children’s perseverance – and, of course, this is helpful – it cannot ultimately impact grit if a lack of passion holds back an individual’s grit score. (In book 3 of this series we explore the concept of passion – or, as we term it, ‘zest’ – as it applies to our wider lives.)

Second, where grit is taken to mean perseverance of effort and the passion element is lost – as, says Duckworth, often happens in critiques of grit – grit can too easily look just like conscientiousness – one of the Big Five personality traits (Rimfield et al., 2016). We know from studies of psychology that personality traits are relatively enduring; one is naturally an introvert or an extravert, for example. So, just as passion is not likely to be receptive to teaching, neither is grit, perseverance or effort.

Third, related to context and culture, Ron Berger suggests that grit is not even an individual trait, but something that people learn when they enter communities where it is the norm: where the culture is such that hard work and determination are expected.

That said, demonstrating grit in an out-of-school area may be helpful in developing more general tenacity. Perhaps a gritty young person who is passionate about a singular long-term goal has gained a valuable insight about learning goals and may come to believe that their success in school is similarly about learning rather than simply performance or test-passing. Dweck’s research tells us that ‘longer-term purposes, even when they are still developing, can provide a reason for students to adopt and commit to learning goals in school’ (2014, p. 10).

Self-control and self-discipline

Tenacity requires the habit of self-regulation, including self-control and self-discipline, and the short-term controlling of impulses. For our purposes, the element of ‘discipline’ demonstrates a series of positive actions (rather than the avoidance of certain actions implicit in the term self-control).

Duckworth and Gross (2014, p. 319) make this point helpfully when they differentiate between the related concepts of self-control and grit in terms of the way in which they determine success through slightly different mechanisms. Self-control is ‘the capacity to regulate attention, emotion, and behavior in the presence of temptation’, while grit is ‘the tenacious pursuit of a dominant superordinate goal despite setbacks’. The two correlate strongly but not completely. While a person may be able to handle day-to-day temptation ‘in the service of everyday kinds of success’, another, more gritty individual has ‘stamina over time in the service of a superordinate goal and extraordinary achievement’ (Akos and Kretchmar, 2017, p. 183).

All of the elements of tenacity we have explored so far are, in effect, useful mindsets for learning at and beyond school. Mindsets are internalised beliefs about the nature of one’s own academic ability or wider capabilities. If a student believes their own efforts will pay off, this high...