![]()

1

COLONIAL EXPANSION THROUGH THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

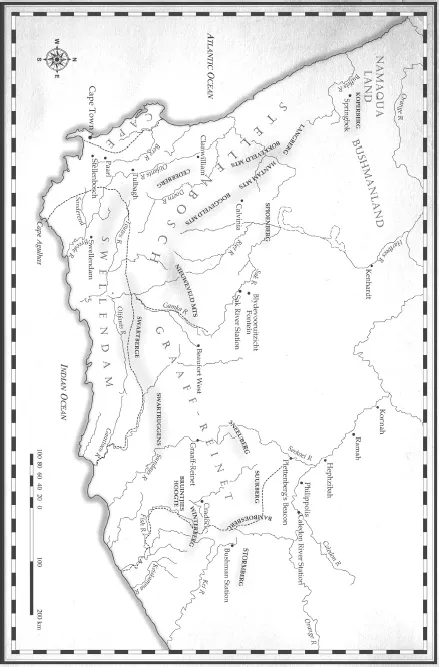

By the start of European colonisation, the San had largely been displaced to the drier and more rugged interior areas by Khoikhoi pastoralists and Bantu-speaking cultivators, both of whom had migrated into the region about two thousand years ago. The first European colonial settlement in southern Africa came in 1652 when the Dutch East India Company set up a refreshment station on the shores of Table Bay. The colony soon started spreading from this base because the VOC, in 1657, decided that allowing independent farmers to work the land was the most expeditious way of meeting the Company’s need for agricultural produce. This opening of the agrarian frontier, together with natural population increase and immigration, ensured colonial expansion from the hub around the garrison and refreshment station from which the city of Cape Town would grow.1 By the end of the 1670s, the indigenous peoples of the Cape Peninsula and the immediate interior, mainly Khoikhoi herders, had been subjugated and dispossessed of their land and livestock. This opened the way for the settlement of the fertile Stellenbosch and Paarl districts, as well as the Swartland area encompassed by the Berg River. It took roughly half a century for most of the arable southwestern Cape to be occupied by European farmers, whose main task it was to supply passing DEIC fleets and the growing settlement at Table Bay with fresh produce.2 Colonisation of the southwestern Cape accelerated in the late seventeenth century as a result of the VOC encouraging immigration from Europe with land grants and offers of free passage (Guelke, 1989: 66).3

From the early eighteenth century, Dutch-speaking, semi-nomadic pastoralists rapidly infiltrated the dry Cape interior, the greater part of which was only suitable for transhumant pastoralism. The difficulties of getting produce to market, in any case, meant that pastoralism was the only viable option for farmers more than a few days’ journey from Cape Town. Where feasible, they did cultivate crops for their own consumption. Population growth and a lack of economic opportunity in the more settled areas fuelled this expansion, while VOC policies also aided the dispersal of stockmen into the hinterland. In 1703, the Cape government lifted its ban on burghers grazing their stock more than a day’s journey from their farms, and from 1714 started issuing grazing rights to extensive 2,400-hectare farms beyond the arable freehold areas in return for an annual rental (Guelke, 1984: 18–24; Botha, 1919: 3–4, 8–10; Giliomee, 2003: 21; Guelke, 1989: 84–91). This was the origin of the Cape’s loan farm system, a form of leasehold which had the effect of accelerating movement into the interior and dispersing the population into tiny isolated groupings across the landscape (Terreblanche, 2002: 157; Elphick & Malherbe, 1989: 11– 18). An important effect of the loan farm system is that tenants were not necessarily tied to a particular tract of land and could move on if they felt the need (Mitchell, 2009: 36).

The penetration of the interior by stock farmers brought into existence a new social group in Cape colonial society, the trekboers. ‘Trekboer’, which means ‘migrant farmer’ in Dutch, refers to the need for these pastoralists to move around with their flocks and herds in search of seasonally available grazing and water using their loan farms as a base. Even the more prosperous, established farmers, those with well-watered loan farms — who are perhaps more accurately referred to as veeboeren (stock farmers) — needed to engage in a degree of transhumance.4 The poorest graziers, unable to afford the rental, did not have loan farms. They tended to live wayfaring lives out of tented wagons, looking for pasturage and hopeful of finding a permanent place to settle. Several families might share a loan farm to reduce costs and for greater security (Penn, 2005: 17, 44; Guelke, 1989: 85–94; Giliomee, 2003: 31–32). They either sold surplus stock to Company butchers travelling through the countryside or, on occasion, drove the animals to Cape Town themselves, taking the opportunity to replenish essential supplies and maintain contact with their cultural and religious roots. Hardy and resourceful, but vulnerable because of their isolation, trekboers often felt insecure and generally were ruthless in their appropriation of natural resources and their treatment of indigenous peoples. Economist Sampie Terreblanche claims that the mercantilist mindset of Europe, which included the notion that a community was justified in using violence or military force against rivals in pursuit of its economic interests, had suffused the world-view and values of colonists at the Cape (Terreblanche, 2002: 154).

The decision by the DEIC in 1699 to lift its ban on livestock trading between colonist and Khoikhoi, in an attempt to improve meat supplies,5 was not only a major impetus for expansion into the interior but also for violence against indigenous peoples. This policy change, and the resultant push into the hinterland, held dire consequences for the pastoralist Khoikhoi peoples occuppying the winter rainfall area of the southwestern Cape, and even for those further north, as far away as Namaqualand. Freebooting colonists saw this as an opportunity to enrich themselves and set up as stock farmers. Within a few years, most Khoikhoi in the region had been stripped of their herds as marauding gangs of colonial raiders, sometimes up to fifty strong, and generally consisting of poorer colonists, adventurers and desperados, spread havoc among indigenous stock-keepers (Penn, 2005: 38–41; Mostert, 1992: 171; Elphick & Malherbe, 1989: 21). Independent Khoikhoi society in the region had been destroyed by the time the VOC reintroduced the prohibition on livestock trading in 1725 (Penn, 2005: 54).

Their land occupied by Dutch-speaking interlopers, Khoikhoi societies along the frontier zone rapidly disintegrated. Some dispossessed Khoikhoi resorted to hunter-gathering, while others migrated beyond the reach of colonial influence. A number became stock raiders, at times in collaboration with San, putting up fierce resistance to further colonial incursions. Epidemics, in particular the smallpox outbreak of 1713, took a huge toll on Khoikhoi society (Ross, 1977: 416–28; Elphick, 1985: 179, 229–34, 236). Importantly, many Khoikhoi were also taken up as labourers by farmers. Their labour was valued by trekboers because the Khoikhoi had intimate knowledge of the natural environment and were highly skilled at animal husbandry. Useful also as guides, hunters and trackers, some became trusted servants. While it initially often suited destitute Khoikhoi to work temporarily for farmers in return for payment in food and livestock — just as it suited farmers to allow such servants to keep stock and exercise a degree of autonomy — their status deteriorated through the course of the eighteenth century. As options for leading an independent lifestyle diminished for the Khoikhoi, so farmers were able to assert greater control over their workers by paying subsistence wages, denying them the right to keep stock, confiscating their animals and retaining children to tie parents to the farm. By the end of the eighteenth century, most Khoikhoi in the employ of farmers were, in effect, forced labourers little better off than serfs (Elphick, 1985: 151– 239; Elphick & Malherbe, 1989: 3, 18–53; Elphick & Giliomee, 1989b: 529, 531–33, 536–37, 546–52; Penn, 1986: 66–67).

As they moved beyond the cultivable southwestern Cape from about 1700 onwards, colonists started coming into conflict with hunter-gatherers. The dynamic behind the encounter with the San tended to be markedly different to that with the Khoikhoi. Whereas traditional Khoikhoi society crumbled in the face of colonial conflict, San social formations proved to be much more resilient. The basic reason for this contrast seems clear enough. The Khoikhoi pastoralist way of life was fragile when confronted with the superior military force at the disposal of settler society and was relatively easily undermined by stock raids or by depriving them of access to grazing or water (Elphick, 1985:170–74; Guelke & Shell, 1992, 820–22; Smith, 1991: 51–52). San bands were, by comparison, hardy and adaptable, being much more mobile and able to live off the land. Their dispersal in small groups across extensive, rugged terrain made it considerably more difficult for the sparsely spread trekboer population to subjugate the San.

Although these farmers did participate in the international capitalist economy by supplying meat and products such as soap, butter, hides and tallow, to passing VOC fleets and the urban settlement at Cape Town, the trekboer economy was not principally driven by market forces but by subsistence considerations (Giliomee, 1989: 424; Guelke, 1989: 89–91; Penn, 2005: 15). Because VOC demand for meat was limited, prices set at levels favouring the Company and the environment harsh, trekboers were not so much commercial ranchers motivated solely by profit than pastoralists with access to a substantial market through which they could dispose of their surplus and procure the goods and services on which their way of life depended. Wagons, guns, ammunition and an array of tools and household goods were their main requirements. Frontier farmers were particularly dependent on their contact with Cape Town for firearms and ammunition, without which they would not have been able to hunt, defend themselves or take the offensive against indigenous people.

These links were also important for trekboer society to maintain an image of itself as Christian and civilised. Communal ties across the scattered settler population were continually reinforced through intermarriage, and a distinct identity maintained through the practice of European-derived customs and material culture (Mitchell, 2009: 75–76, 90–91; Newton-King, 1999: 20–25, 150–209). Besides the typical trekboer family conducting daily home religious services and saying prayers at mealtimes, frontier farmers usually travelled to Cape Town or the nearest village church to solemnise marriages and baptise children. They also intermittently employed itinerant teachers to impart a smattering of education to their children (Van der Merwe, 1938: 246– 52; Newton-King, 1999: 45, 188, 208; Giliomee, 2003: 33–34; Guelke, 1989: 93, 96). Social networks were renewed at nagmaal (communion) services that periodically drew together burgher families from far and wide, and less regularly at auctions to settle insolvent estates (Mitchell, 2009: 126, 146; Newton-King, 1999: 254). Militia service was the communal activity that most starkly emphasised settler identity and interests in opposition to those of autochthonous peoples.

Their muted profit motive, however, did little to mitigate the ultimate fate of hunter-gatherer peoples on the Cape frontier, as trekboer demographic growth, coupled with growing VOC demand for meat through the eighteenth century, ensured colonial expansion into the interior and the displacement of indigenous groups. The dynamic behind the violence between trekboer and San thus had less to do with a voracious, international, capitalist market for meat than with the far older, more pervasive displacement of hunter-gatherers by farming communities (Brody, 2000: 6–7, 143–50). Production for the market was not irrelevant to this process because overgrazing as a result of trekboer ignorance and a desire to turn a profit resulted in the progressive reduction in the carrying capacity of the veld as it was stripped of edible plants and replaced by vegetation their stock found unpalatable (Sparrman, vol. I, 1975–77: 238– 39; Newton-King, 1999: 98).

Because of limited water resources in the Cape interior and the nature of transhumant pastoralism, the trekboer economy was expansive, and a relatively small trekboer population, together with their dependants, appropriated large swathes of land for their use. With a growing number of colonists entering the interior as farmers through the eighteenth century, and as the sons of trekboers set themselves up as independent graziers, there was intensifying pressure on resources and a continous drive to find new pastures to exploit. Trekboers, though thin on the ground — there being no more than about 600 independent stockholders by 1770, perhaps 1,000 by the end of the eighteenth century, with the total freeburgher population having reached nearly 15,000 by 1795 (Ross, 1994a: 127; Guelke 1989: 85) — were nevertheless able to control extensive tracts of land. Their access to superior military technology allowed colonists to take possession of scarce permanent water supplies, which in turn gave them dominion over the surrounding grazing (Guelke & Shell, 1992: 803–5, 816, 824; Penn, 2005: 111). By establishing their farms around perennial springs and water holes in the parched landscape, and by being able to defend their occupation of these strategic nodes, trekboers were able to exercise power over an area of land greatly disproportionate to their numbers, and had an incommensurate impact on the lives of indigenous inhabitants.

From 1700 onwards, settlers started moving across the Berg River into the Tulbagh basin about 100 kilometres from Cape Town. Here they encountered significant resistance, both from dispossessed Khoikhoi as well as from San, in particular a group known as the Ubiqua who had a reputation as fearsome stock raiders. By the early 1710s, pastoral farmers were migrating northwards into the Olifants River valley and beyond that into the Bokkeveld across the Cederberg Mountains. The intrusion of trekboers into this region provoked concerted Khoisan resistance, and it was not until 1739 that this frontier zone was closed when a series of major military campaigns by frontier farmers, organised by the Cape government, quelled indigenous opposition. From about 1740, the frontier advanced rapidly as trekboers started moving north and east of the Bokkeveld Mountains and beyond the Olifants River valley into the harsher environment of the escarpment formed by the Hantam, Roggeveld, Nieuweveld and Sneeuberg mountains. The escarpment marked the transition between the narrow coastal plains and the open expanses of the interior plateau, as well as between the winter and summer rainfall areas. Farmers needed to be even more mobile in this environmental zone to exploit both summer and winter grazing to obtain year-round nourishment for their stock (Van der Merwe; 1937: 1–10; Penn, 2005: 19–22). The further colonists moved from Cape Town, the more tenuous VOC control over its subjects became, and the greater the degree of lawlessness in the border regions and beyond.

Across the escarpment lay the Cape thirstland, an uninviting prospect for both San and frontier farmer. Over the next three decades, a growing number of trekboers established loan farms along the escarpment in the face of sporadic but intensifying resistance from San and Khoikhoi refugees not prepared to retreat into the arid reaches of the Great Karoo and Bushmanland. By the late 1760s, pressure on resources reached critical levels, initiating sustained and coordinated Khoisan insurgency and guerrilla attacks against settlers along the length and breadth of the frontier (Penn, 1995: 195–96; 1989: 9; Newton-King, 1999: 77; Lye 1975: 21–22). During the last three decades of the eighteenth century, San resistance halted the colonial advance into the interior and in places even rolled it back (Marks, 1972: 73–74; Penn, 2005: 81–82, 164; Van der Merwe, 1937: 12–24). In some areas drought, and along the eastern frontier, horse sickness in lower-lying wetter parts, also informed trekboer decisions to abandon outlying farms. The stalling of the frontier advance precipitated a major crisis for trekboer society, which depended on continuous expansion to accommodate demographic growth and compensate for the deterioration of pastures in settled areas. During this period, trekboers, with the help of the VOC government, embarked on an exterminatory military offensive against the San (Van der Merwe 1937: ch. 2; 1938: ch. 3; Guelke, 1989: 84–93; Newton-King, 1999: chs. 4–6; Penn, 2005: ch. 4; Green, 1955: 27).

Adapted from The forgotten frontier, N. Penn (2005), Cape Town: Double Storey Books, p 220.