Introduction

Intellectual activist – or activist intellectual?

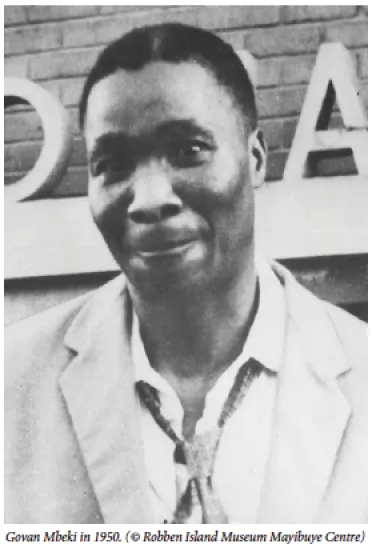

Govan Mbeki was born on 8 July 1910. The Union of South Africa was barely six weeks old: a new state, delivered by compromise and negotiations at a constitutional conference. Political power was vested firmly in white hands: a limited black franchise operated only in the Cape Province. The Prime Minister was Louis Botha, recently a Boer guerrilla general and now an adroit politician.

Govan died on 30 August 2001. The democratic Republic of South Africa was already seven years old: a fledgling state midwifed by negotiations and concessions at a constitutional conference. Its constitution provided for universal suffrage: electoral power for the black majority was ensured. Its second President was Thabo Mbeki, Govan’s eldest son, recently an exiled activist and now an adroit politician.

I like to think that Govan Mbeki might have twinkled approval of the echoes and comparisons in the paragraphs above. A keen student of history, he frequently drew lessons for the African nationalist struggle from the successes of Afrikaner nationalism. An author and journalist who wrote about politics and economics for over 60 years, he enjoyed finding a telling phrase or instructive detail. And as an acutely political being, he was profoundly aware of just how great were the changes brought to South Africa in the final decade of his long life.

Central to those changes was the part played by the African National Congress (ANC); in turn, the most prominent opponent of the National Party, its negotiating counterpart and its political successor. The ANC may have been founded in 1912, but its key shifts took place from the 1940s onwards. Its history spools out in a dialectical relationship with that of the National Party (NP), elected on an apartheid platform in 1948.

The first NP Prime Ministers, D.F. Malan and Hans Strijdom, largely ignored the ANC, even when it first won a mass base in 1952 with a campaign rejecting the ‘unjust laws’ of apartheid. H.F. Verwoerd banned the movement in 1960, locked up its leaders and criminalised its every action. B.J. Vorster and P.W. Botha, through the 1970s and 1980s, demonised the exiled body and its army, infiltrated its ranks and bombed its bases. By doing so, they ensured its iconic status in township streets, in classrooms and lecture halls, in hearts and minds. The surging internal resistance spearheaded in the 1980s by the United Democratic Front (UDF) was increasingly explicit in its adherence to an idealised ANC, so that F.W. de Klerk finally decided that it was safer to legalise the movement. He believed that the collapse of Soviet power also weakened the ANC so that it might be outflanked in a negotiated settlement.

And if the ANC’s history is central to an account of the liberation struggles waged against white minority rule, Govan Mbeki’s politics, career, writings and identity were shaped by a profound commitment to the organisation. Not that he was an apparatchik or uncritical loyalist: far from it. As this biography shows, his long-held and heterodox belief in the political importance of rural people cut little ice in an overwhelmingly urban nationalist movement. Later, his co-authorship of the ‘Operation Mayibuye’ document was a source of acute controversy. Finally, on Robben Island Govan Mbeki and Nelson Mandela fell out. The two were deeply divided on doctrinal grounds and over strategies, and the gulf was widened by contrasting personalities. Despite these strains, and notwithstanding the extent to which Govan’s socialist beliefs imparted a particular spin to his nationalism, he died as he had lived – an ANC standard-bearer. His final request to Dr Mamisa Chabula, his physician and friend, was to be buried in his favourite ANC blanket and cap.

*

I first met Oom Gov in February 1988. Shortly after his release from Robben Island in November 1987, because of his uncompromisingly revolutionary public statements he was subjected to a banning order which restricted his movements and meetings with others. A couple of years earlier, I had written briefly about his political activities in the Transkei during the 1940s; had squirrelled away various pieces of his journalistic output; and was very excited at the prospect of finally meeting, and interviewing, the author of The Peasants’ Revolt. The meeting was set up by Dullah Omar, then a lawyer in close contact with senior ANC prisoners. I flew from Cape Town to Port Elizabeth where I was met at the airport by a youngish man. He drove me from the airport to a second car; it then whisked me off to a house in Korsten. Govan – I was told – had made his way to the same venue by a similarly circuitous route.

We went to a garage at the end of the driveway where two chairs and a small table had been placed for our interview. Govan motioned me to my chair, but sat himself on the floor, back against the wall, long legs straight out ahead of him. ‘I got used to sitting like this on the Island,’ he said apologetically, ‘but do begin.’ And my first memories of the encounter are of the cheap sandals on his feet, which sat oddly with the neatly pressed trousers he wore. That – and his hands: large hands, with long, spatulate fingers, now clasped together as he chased a memory, then alive with gesture, ticking off the points he wanted to emphasise.

When I look now at the transcript of that first interview, I realise that while he was courteous, Govan was also guarded and cautious. It helped that he was familiar with my book on the history of South African peasants – that was why he had agreed to meet me, even though being interviewed for an intended publication transgressed his banning order – but there were topics on which his responses concealed quite as much as they revealed. In subsequent interviews conducted in Port Elizabeth and in Cape Town, the tenor of his responses became warmer, more open. I used to enjoy mentioning something that I had come across in the archives, prompting his surprise – ‘now, yes, how did you know that?’ – and eliciting that unforgettable, deep laugh. In this book, all direct quotations from Govan are drawn from the transcripts of these interviews; other sources are identified separately.

He was quietly pleased that I was researching his life and wrote to me quite frequently, amplifying remarks he had made, retrieving a forgotten detail, or commenting on drafts of seminar papers. I have to confess that he also used our correspondence to chide me gently, urging me to finish the book. It has taken me a very long time to do so. I hope only that finally it does some form of justice to his life, the life of an activist and of an intellectual, in which activism and intellectualism were not opposites but complementary.

1

Home comforts and family histories

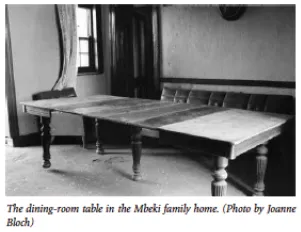

When Govan Mbeki spoke about his childhood, his face softened and he conveyed a sense of comfort, warmth and stability. The family house – in Nyili village, Mpukane ward, in the Nqamakwe magistracy – was ‘a solid house, very well built’ and the furniture was handsomely carpentered, ‘some of the most beautiful furniture I ever saw’. He spoke with a nostalgic pride about the dining-room table, purpose-built for his father. ‘With its extra leaf in, with all its leaves in, it could seat sixteen people – sixteen, all around it. For special occasions, yes.’ Even in its more compact form for everyday use, the table would have been ringed by a good number of chairs. Govan had a brother and three sisters – all older than him – and in addition his three half-sisters made extended stays in their father’s home. It was a house bustling with women, and one can easily imagine the affection and attention directed towards the laatlammetjie. Govan recalled being ‘very close’ to his mother, and told the film-maker Bridget Thompson that when she attended a wedding, she would tuck a piece of the cake into her doek to take home for him: ‘And wherever she went, if she got anything nice, she would always bring something home for me.’ His sisters also helped raise him, teaching him games and passing on songs they learned at school, and recounting Xhosa fables.

Childhood memories are often rose-tinted. It would be difficult to know, based on Govan’s account of his early years, that the family’s modest prosperity was being squeezed around the time of his birth; that his ageing father had been dismissed from his post in disgrace; or that, as he grew up, his family would begin a genteel slide: not into outright poverty, but into more straitened circumstances. But before these pressures began to tell, Govan’s father, Skelewu Mbeki, was unmistakably a member of a ‘progressive’ or modernising peasantry that enjoyed its heyday in the Cape Colony and Transkeian Territories in the second half of the 19th century. And like many others at the upper reaches of this peasantry, the Mbeki family was Mfengu; had converted to Christianity; enjoyed modest wealth through a combination of peasant farming and entrepreneurship; and channelled a good portion of its income into a self-consciously modern lifestyle and the best education available for the children.

Skelewu’s grandfather, Nonkasa, was an amaZizi herdsman: like many others of that clan, he was swept up in the population movements of the mfecane, leaving what is today Bergville district in KwaZulu-Natal. Driven south, Nonkasa was probably among the first few thousand refugees who presented themselves at the Great Place of the Xhosa king, Hintsa, in the 1830s. (When in prison on Robben Island, Govan Mbeki was usually greeted, respectfully, as Zizi – his clan name. But he deflected my questions about the usage, and he consistently sought to underplay references to his ethnicity: ‘I would rather you avoid reference to tribal origin,’ he wrote to me. I realised only subsequently that Govan – like Oliver Tambo – was highly sensitive to the potential discord that ethnic identities might trigger in the nationalist movement.) Nonkasa entered the Cape Colony in 1836 with two sons, Mfeti and Mbeki, and the latter’s seven-year-old son, Skelewu. The family lived briefly near Peddie, then settled close to the Methodist base and school at Healdtown. Here, Skelewu attended school, converted to Christianity, and married another Mfengu convert, with whom he had three daughters.

In 1866 or 1867 Skelewu was among the Mfengu encouraged by the Cape government to move back across the Kei River and settle in the new British protectorate of ‘Fingoland’ between the Kei and Mbashe rivers (part of the magistracies of Nqamakwe, Tsomo, Idutywa and Butterworth). Skelewu was accompanied by a number of his amaZizi clanspeople, and they were allocated Mpukane ward (or location, as it was called at the time). Skelewu was recognised at the time as a leader of the ward. ‘My father was chief and recognised as such by the people,’ Govan Mbeki wrote subsequently. He exercised the authority of a headman for a number of years before his official appointment in July 1890.

It was not only by virtue of office that Skelewu commanded respect in Mpukane. He was also one of the most prosperous men in the ward, and demonstrated this by building a handsome house, built of stone carved by masons at Blythswood mission school. It was (Govan averred) the first stone house owned by an African in the entire district of Nqamakwe. The house stood a few hundred metres from Skelewu’s farmland. He owned about 16 morgen of land (or about 30 acres), held under Glen Grey title, but on a plot about four times as large as most Glen Grey land grants. The land was all fenced. In addition to maize and vegetables for household use and for sale, Skelewu raised pigs and poultry. Like other successful peasant farmers, he invested in livestock, and owned goats, sheep, horses and cattle. His cattle herds were too numerous to graze on his own land, and he ‘leased’ them out in the loan system known as inqoma. Selected cattle were fattened on a friend’s farm in Komgha district before sale at the King William’s Town market. His most profitable enterprise during the 1870s and 1880s was transport-riding. Before the advent of rail and motor lorries, much of the commercial freight in the Cape Colony and Transkei was handled by peasants wealthy enough to own wagons and teams of oxen. Transport-riding was one of the most effective methods of accumulation available to rural households. Skelewu employed drivers who plied his wagons between King William’s Town and trading stores across the Transkei.

In 1893 the widowed Skelewu married for a second time. His new wife, Govan’s mother, was Johanna Mabula, daughter of a Methodist preacher from Healdtown district. Forty years younger than Skelewu, Johanna bore him five children, three daughters and two sons, Sipho and Govan Archibald Mvunyelwa (‘for whom the people sing’). She was an impressive presence in Govan’s early life. Fluent in Xhosa, Dutch and English, she was well known in Mpukane. Because of her husband’s standing, many local people passed to pay their respects – and Johanna would welcome them with liberality. The visitors did not need to say they were hungry (Govan recalled): ‘Whenever you came, the first thing you were offered was food or tea, things like that.’

Headmen like Skelewu were indispensable agents of colonial control, responsible for translating rules and regulations – over land, livestock, travel and taxes – into everyday observance. Their ‘loyalty’ and ‘reliability’ were under constant scrutiny; their performance and shortcomings occupy countless pages in the magistrates’ records. An instance of this occurred in June 1911. The octogen...