![]()

1

THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH HISTORY AND ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING OF THE HOCKING VALLEY

Elliot M. Abrams and AnnCorinne Freter

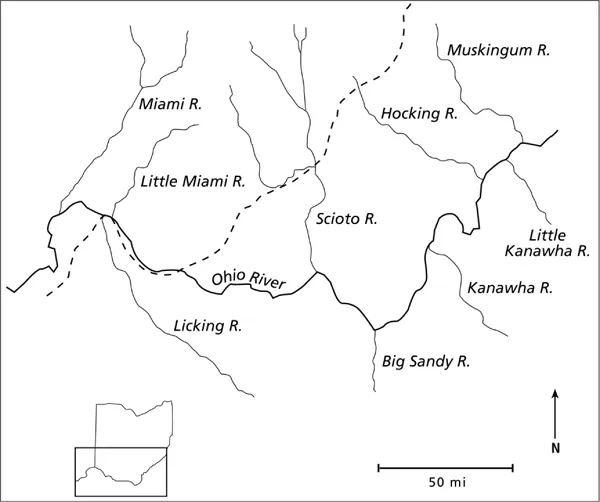

BY THE NINTH MILLENNIUM B.C., descendants of the original prehistoric immigrants to North America migrated into what is today the Hocking River Valley of southeastern Ohio (fig. 1.1). In the wake of postglacial warming some twelve thousand years ago, these first familial communities moved within and between river valleys for economic and social reasons. Food acquisition was centered on hunting and gathering wild resources widely dispersed across the landscape. Over time a greater permanence of place within specific river valleys was established and basic economic, social, and political lifeways began to change, predicated on a growing dependence on gardening. During the first millennium B.C., burial mounds and circular earthworks were built as part of religious ritual and social ceremonialism. By the end of the first millennium A.D., gardening of local species yielded to larger-scale agriculture involving the introduced crops maize and beans. These more sedentary villages could have eventually expanded into chiefdoms or small kingdoms had the devastating impact of the Euro-American conquest not irreversibly altered the lives, history, and cultural-evolutionary trajectory of the indigenous population.

This brief general outline of preconquest culture change within the Hocking Valley applies to hundreds of riverine societies in the Mississippi River watershed. The ethnohistoric record, describing Ohio Valley societies at the time of contact, offers insights into the lives and specific cultures of the Shawnee (Callender 1978; Howard 1981), the Delaware (Wallace 1990; Olmstead 1991), and other groups anthropologists classify as tribes. This general trajectory of tribal origins and growth can be written for societies in nearly all regions of the world since the complex pattern of change from small nomadic bands to more sedentary tribes represents one of the most significant transitions in the cultural evolutionary experience of humankind.

FIG. 1.1. The Hocking River Valley. Dotted line represents southern extent of Wisconsin glacial advance, ca. 10,000 B.C. (Modified from Seeman and Dancey 2000.)

Each of the indigenous riverine societies of the central United States was historically unique. Although influenced to varying degrees by groups external to their society, each riverine community met the demands of the dynamic opportunities and challenges presented by its immediate natural and social ecological setting. Since all archaeology is ultimately local, it is incumbent on archaeologists to materially document and attempt to explain this cultural variability within a common general evolutionary schema.

This book moves us closer to a definition of the cultures and patterns of change affecting those indigenous societies of the Hocking Valley from ca. 2500 B.C. to A.D. 1450. Those four millennia witnessed the establishment and expansion of tribal communities, and the overarching goal of this book is to better discern this process of tribal formation. This involves the reconstruction of the demographic, economic, and sociopolitical cultural systems specific to each time period so that a description of sequential change or an archaeological culture history of the valley is possible. Based on this culture history, our final goal is to offer explanations for such instituted tribal cultural changes within the framework of ecological anthropology. The result is the most current anthropological and comparative presentation of prehistoric tribal formation for this tributary of the Ohio River.

Past Research

The earliest archaeological research in the Hocking Valley was conducted with little if any interest in the indigenous population; in fact, the earliest efforts were often intended to deny native groups their rightful heritage as occupants of the midcontinent (Patterson 1995). Instead, the building of the ancient earthworks was credited to “the moundbuilders,” a society of varied origins who, to some, were replaced by the Native American population (Silverberg 1986). “The idea that Indians themselves drove off or killed the glorious moundbuilders made it easier to rationalize their inevitable demise as a form of historic justice” (Meltzer 1998, 2).

Support for the “moundbuilder race” most notably came from the early, antiquarian archaeological effort of Squier and Davis in their classic Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley (1848). In this volume, earthworks throughout the midcontinent are defined in terms of form, location, and in many cases interior contents from trenching excavations. The authors note that, relative to other areas of Ohio, “[t]here are very few enclosures, so far as known, in the Hocking river valley; there are, however, numerous mounds upon the narrow terraces and on the hills bordering them. In the vicinity of Athens are a number of the largest size, and also several enclosures” (100). This latter reference alluded to those earthworks centered in The Plains, as mapped by S. P. Hildreth in 1836 and published in Squier and Davis’s volume (plate 23, no. 2). The only other earthwork from the Hocking Valley published in their volume is the Rock Mill earthworks near Lancaster.

Their publication popularized the presence of earthworks, which in the Hocking Valley led to extensive trenching excavations and further mapping of mounds both in The Plains and throughout the valley (Andrews 1877). This focus on burial mounds in quest of artifacts for museum display or personal gain typified these years of antiquarian archaeology in this and many other regions of the Midwest. Regrettably, none of the artifacts or skeletal data retrieved by E. B. Andrews, the primary excavator, have been relocated and are lost to museum researchers.

A research focus on Hocking Valley mound locations continued, achieving its grandest expression in William Mills’s Archaeological Atlas of Ohio (1914), which describes the results of Mills’s travels through Ohio “verifying wherever possible those monuments already known and at the same time adding new records to the map” (iii). He notes the presence of numerous mounds and circular and square enclosures throughout Athens, Fairfield, and, to a lesser degree, Hocking Counties. Mills adds that The Plains “is dotted with mounds and enclosures so abundant that from almost any one of them it is possible to see another” (5).

Archaeology conducted by professionals in the first half of the twentieth century was oriented toward artifact description, the goal being to generate archaeological cultures based on the cataloging of traits (Willey and Sabloff 1980). This was exemplified by Emerson Greenman’s (1932) excavation of the Coon Mound in The P...