- 236 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

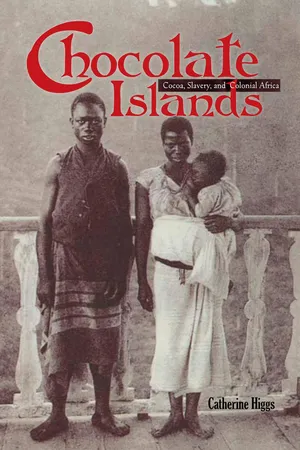

In Chocolate Islands: Cocoa, Slavery, and Colonial Africa, Catherine Higgs traces the early-twentieth-century journey of the Englishman Joseph Burtt to the Portuguese colony of São Tomé and Príncipe—the chocolate islands—through Angola and Mozambique, and finally to British Southern Africa. Burtt had been hired by the chocolate firm Cadbury Brothers Limited to determine if the cocoa it was buying from the islands had been harvested by slave laborers forcibly recruited from Angola, an allegation that became one of the grand scandals of the early colonial era. Burtt spent six months on São Tomé and Príncipe and a year in Angola. His five-month march across Angola in 1906 took him from innocence and credulity to outrage and activism and ultimately helped change labor recruiting practices in colonial Africa.

This beautifully written and engaging travel narrative draws on collections in Portugal, the United Kingdom, and Africa to explore British and Portuguese attitudes toward work, slavery, race, and imperialism. In a story still familiar a century after Burtt's sojourn, Chocolate Islands reveals the idealism, naivety, and racism that shaped attitudes toward Africa, even among those who sought to improve the conditions of its workers.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

NOTES

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Glossary

- Prologue Joseph Burtt and William Cadbury

- One Cocoa Controversy

- Two Chocolate Island

- Three Sleeping Sickness and Slavery

- Four Luanda and the Coast

- Five The Slave Route

- Six Mozambican Miners

- Seven Cadbury, Burtt, and Portuguese Africa

- Epilogue Cocoa and Slavery

- A Note on Currency

- A Note on Sources

- Abbreviations in the Notes

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index