![]()

1

A Night at the Club

These are the stages which all men propose to play their parts upon, For clubs are what the Londoners have clearly set their hearts upon.

—Theodore Hook, “Clubs”

A nineteenth-century clubman, James Smith, once recounted his clubland routines:

At three o’clock I walk to the club, read the journals, hear Lord John Russell deified or diablerised, do the same with Sir Robert Peel or the Duke of Wellington, and then join a knot of conversationists by the fire till six o’clock. We then and there discuss the three per cent. consols (some of us preferring the Dutch two-and-a-half), and speculate upon the probable rise, shape, and cost of the new Exchange. If Lady Harrington happens to drive past our window in her landau, we compare her equipage to the Algerian ambassador’s; and when politics happen to be discussed, rally Whigs, Radicals, and Conservatives alternately, but never seriously, such subjects having a tendency to create acrimony. At six the room begins to be deserted; therefore I adjourn to the dining-room, and gravely looking over the bill-of-fare, exclaim to the waiter, “Haunch of mutton and apple tart!” These viands dispatched, with the accompanying liquids and water, I mount upward to the library, take a book and my seat in the arm-chair and read till nine. Then call for a cup of coffee and a biscuit, resuming my book till eleven; afterwards return home to bed. (quoted by Girtin, 132)

Numerous are the accounts of other clubmen more adventurous than Smith, who often ended their nights at the club with cards or billiards until 2:00 in the morning.1 It was not uncommon for Victorian men to belong to several clubs and to have their favorites for different activities and at different times of the day and night. With clubs typically opening at 8 or 9 a.m. and closing at 1:00 or 2:00 in the morning, these institutions could fill up the lives of nineteenth-century men.2 The Victorians were frank about the multifaceted appeal of clubland’s social geography. They often acknowledged the male desire to escape domestic boredom and responsibilities; to enjoy pleasures safely behind closed doors and indulge in mischief among loyal brothers; to seek the male sociability afforded by clubland’s culture of professional networking; and, even in the ostensibly nonpolitical clubs, to engage in the political debates of the day beyond earshot of women.3 Indeed, the social observer Mrs. Gore in her Sketches of English Character (1846) admits that the coed days of Almack’s Assembly Rooms were brought to a close because of the heated politics of the French Revolution (25).

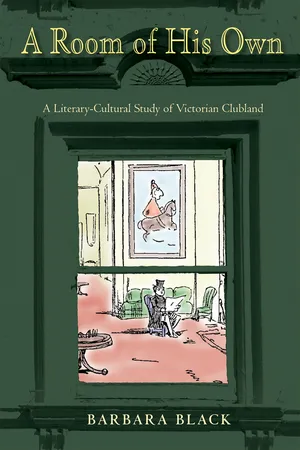

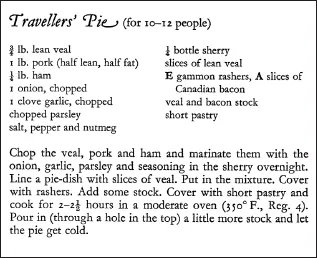

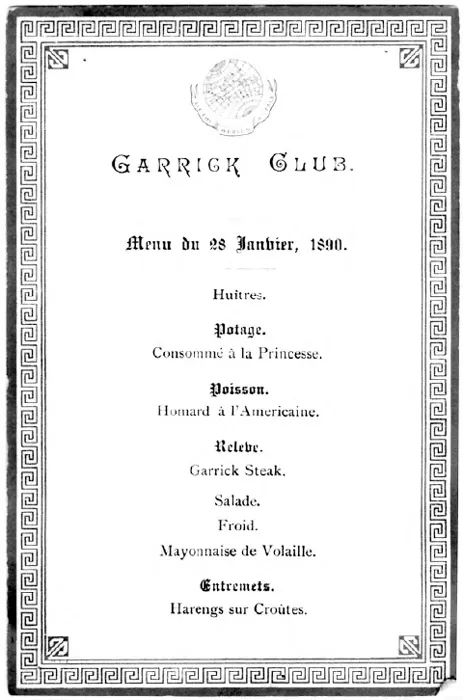

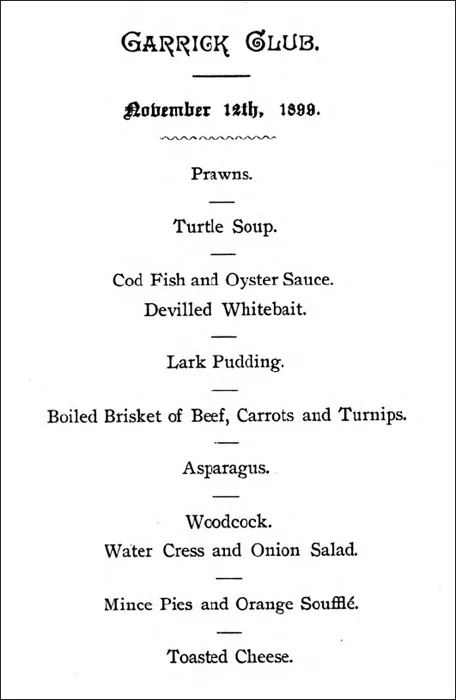

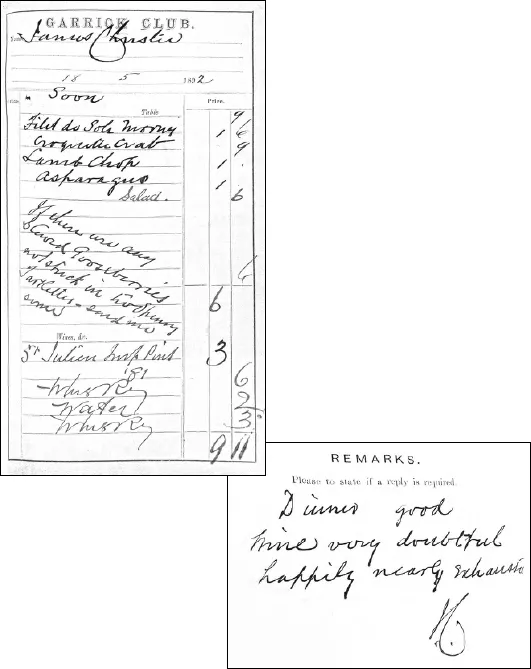

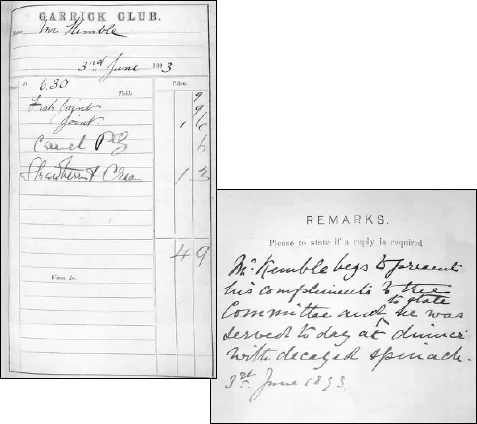

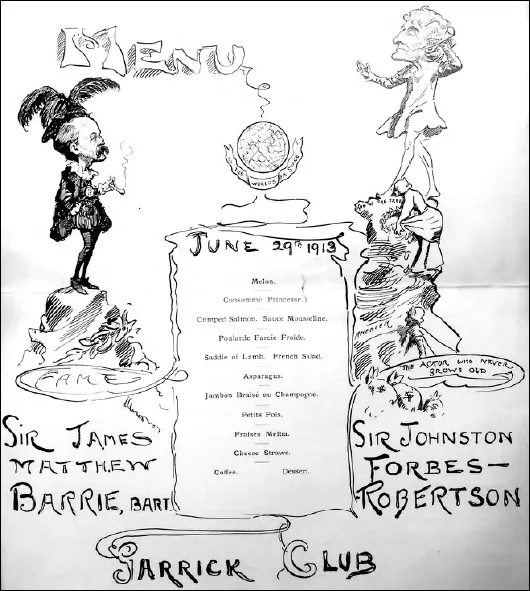

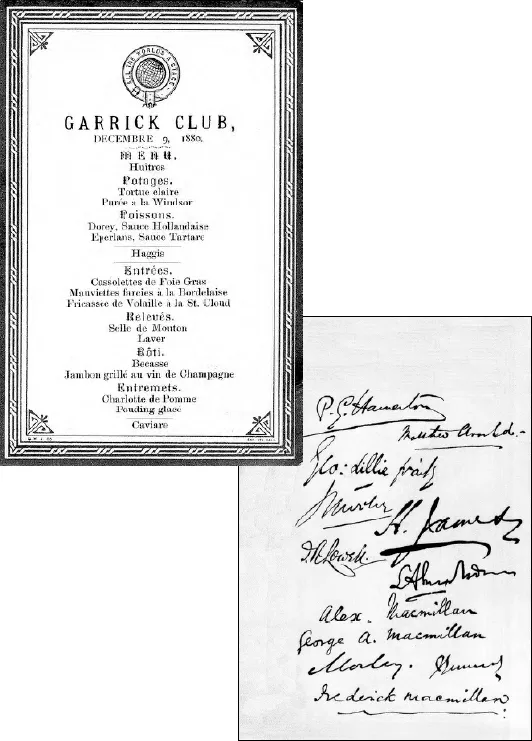

A more detailed understanding of the urban routines of upper-class men and, as the century progressed, increasing numbers of aspiring middle-class men can clarify for us today what it meant to spend one’s nights, and even one’s days, in Victorian London’s clubs. As Travellers member Sir Almeric Fitzroy pronounced, clubs were “where social gratification was the ruling impulse” (9); thus, the undisputed centerpiece of club life was dining and drinking. For many club brothers, what the table offered was paramount, and clubs carefully cultivated their reputations as desirable places in which to eat and drink.4 The popularity of the Reform was due as much to the fame of celebrity chef and food activist Alexis Soyer, the Reform’s head chef from 1838 to 1850, as it was to the club’s political sympathies. Martin Thomas Frost, head cook at the Travellers for many years until his death in 1875, earned the attention of David Livingstone and was hired to be Livingstone’s cook in Africa. And Florence Nightingale, known for her appreciation of fine food, required that her cook train at the Travellers, as did other cooks throughout the century. Clubs could even boast of signature dishes, as did Boodles with its “Boodle’s Cake,” an orange fool, and the Travellers with its “Travellers’ Pie” (fig. 1.1). Soyer’s “Cotelettes de Mouton à la Reform” became a famed dish (fig. 1.2), and Thackeray was known to love the Reform’s boiled beans and bacon. Victorian club menus tended to feature traditional British fare, with an emphasis on the mutton chop, and some clubs, such as the Garrick, resuscitated the tradition of the hallowed Beefsteak dinner (fig. 1.3). Turtle was often reserved for special events or, as in the case of the Garrick, for bon voyage dinners for dignitaries about to set off on trips (fig. 1.4). Two dinner bills of James Christie, a loquaciously appreciative member of the Garrick when it came to his meals there, reveal a common practice: both satisfied and dissatisfied diners were directed to write comments on the backs of their bills, which the House or General Committee, acting swiftly, annotated in way of response (figs. 1.5–1.6). The bill of Mr. Kemble, of the theatrical dynasty, is similarly annotated (fig. 1.7).

FIGURE 1.1. Recipe for “Travellers’ Pie.” Courtesy of the Travellers Club.

FIGURE 1.2. Recipe for “Cotelettes de Mouton à la Reform” with “Sauce à la Reform” by Alexis Soyer. From The Gastronomic Regenerator, 1847, 294–95, 17–18. Reprinted in George Woodbridge, The Reform Club, 1836–1978,173.

FIGURE 1.3. Garrick Club Beefsteak dinner menu, January 28, 1890. Courtesy of the Garrick Club.

FIGURE 1.4. Garrick Club dinner menu, November 12, 1899, featuring turtle soup. Courtesy of the Garrick Club.

FIGURE 1.5. Garrick Club dinner bill of James Christie, May 18, 1892, with remarks on back. Courtesy of the Garrick Club.

FIGURE 1.6. Garrick Club dinner bill of James Christie, November 3, 1891, with remarks on back. Courtesy of the Garrick Club.

FIGURE 1.7. Garrick Club dinner bill of Mr. Kemble, June 3, 1893, with remarks on back. Courtesy of the Garrick Club.

FIGURE 1.8. Illustrated Garrick Club house dinner menu, June 29, 1913. Courtesy of the Garrick Club.

As the century progressed, the time of the main meal in clubland shifted from 2–4 p.m. to 6 p.m., and then again to 8 p.m.; however, the cost of dining remained relatively consistent. At the Athenaeum, for example, the average cost of dinner was 2s 9 3/4d in 1842, which had been raised only to 3s 3d sixty years later (Lejeune, 11). Most clubs hosted special dinners, typically called house dinners, which featured elaborate seating plans that granted the head chair to a particularly eminent member. By the turn of the century, it became customary to announce house dinners with cleverly illustrated menu cards that both promoted the event and served as mementoes of the evening (fig. 1.8).5 Earlier in the century, menu cards might be signed by those in attendance and preserved as worthy collectibles. One such menu features the autographs of the famous MacMillan brothers, Matthew Arnold, and Henry James (fig. 1.9). The business of the Wine Committee, especially the ordering for the wine cellar, was a prominent agenda item in committee minutes.6 With its motto “Sodalitas Convivium,” meant to highlight the pleasures of both friendship and the table, the Savile Club insisted that all members have agreeable manners, which would be showcased according to the club’s “table d’hôte” principle of all diners seated at the same table eating the same meal (in contrast to the restaurant principle of different meals for different diners). In short, clubbing placed a premium on taking the time, and having the leisure, for consumption and conviviality; it was a way of life, a set of cultural practices, that provided an escape from the workaday world.7 As Garrick Club member Kingsley Amis once bemoaned in devotion to the club bar, “‘We might go straight in to lunch’ was deemed the most odious statement heard in clubland” (quoted by Binns et al., 27).

FIGURE 1.9. Garrick Club menu card, December 9, 1880, with autographs of diners on back. Courtesy of the Garrick Club.

Correspondence, conversation, and news also contributed to the life-blood of club culture. Certain clubs, such as the Savage, the Garrick, and the Savile, were particularly well-known for their lively culture and witty membership;8 however, even a club such as the Travellers, the model for Arthur Conan Doyle’s brooding Diogenes Club, featured the long central table in the coffee room, where club brothers sat down to join together for a lively repast.9 The hunger for news made writing and reading a central occupation of clubmen. Most clubs assiduously built up their libraries and handsomely decorated and furnished their reading rooms; all provided their membership with the day’s morning and evening papers. Accordingly, one of the drawing room waiter’s major duties at the Garrick was to make certain that “newspapers and books that arrive throughout the day should be cut-stitched and arranged” and that “writing rooms should be in order” (Garrick, “Responsibilities,” c. 1905). That great imprimatur of belonging, club stationery was immensely important to clubland. Both the symbol and the tool of male social significance—the smart phone of its day, if you will—correspondence on club stationery was one of clubland’s great entitlements and conveniences.10 At the Garrick Club, the “Boys’” duties (during a 9:00 a.m.–10:00 p.m. workday) included taking messages as they arrived to any member in the house and collecting letters from post boxes stationed in various clubhouse rooms, as well as carrying the letters to the post office every hour (Garrick, “Responsibilities”). According to this same in-house document, the messenger was required to take the last post to Charing Cross at 6:45 p.m. The Minutes of the Committee, 1828–29 from the Travellers Club refer to the two-guinea payment to the postal service for early as well as evening delivery of the post, what Fitzroy in his History of the Travellers’ Club amusedly calls a veritable bribe to a state service (36–37).11 Typically, club runners would deliver the post six times a day, a service that underscores the importance of connections and news in the network culture of Victorian clubland. At the Oriental, the boy page called for the last post at 1:00 a.m.

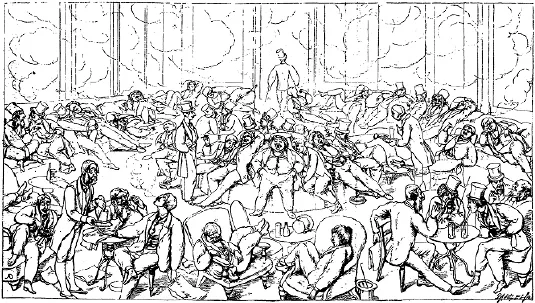

FIGURE 1.10. “The Smoking Room at the Club,” from “Bird’s-Eye Views of Society,” illus. by Richard Doyle. Cornhill Magazine, 1862.

Key among the clubs’ other attractions were smoking and gaming. Although today we assume cigars to be the most recognizable metonymy for club culture, smoking was a controversial subject in early-Victorian clubland.12 The problem of ventilation and the risk of fire, along with the possibility of unpleasantness to nonsmoking club brothers—surely an inconvenience that would challenge the very culture of comfort that was fundamental to clubland—made clubs slow to embrace smoking. The dominant clubland presence of the retired military at midcentury, particularly the Crimean War veterans who found themselves back at home and were, in large numbers, smokers, eventually forced Victorian clubs to meet this demand (fig. 1.10). In the early years of the Reform Club, for example, smokers were consigned to two billiard rooms and a small space that is now a study room; however, in 1856, members voted to use the upper library as a new smoking room, leading eventually to smoking being permitted in most areas of the club (Urbach, 7). White’s introduced its first smoking room in 1845 (Girtin, 94). The Savage became known for its smoking concerts, and Thackeray was instrumental in introducing smoking to the Athenaeum in 1862, when the club agreed to provide one tiny smoking room at the top story of its clubhouse.13 Gaming was also a pastime for whiling away the hours in one’s club, which spoke to Victorian clubland’s immediate roots in Regency dandy culture.14 Although certain clubs, such as White’s and especially Brooks, with its infamous betting books, were most closely associated with gambling, clubs typically provided its members with gaming opportunities, which included billiards and card games such as faro and whist. Strict limits on betting stakes were consistently observed across Victorian clubland—hence the typicality of Rules XXVI and XXVII from the 1836 Reform Club Rules Book: “The Game of Hazard shall not, on any account, be played, nor shall Dice be used in the Club House” and “No higher Stake than Half-a-Guinea Points shall ever be played for” (15).15 According to nineteenth-century gossip and society writer Captain Charles Gronow, the genesis of this institution-wide restriction can be found in the Duke of Wellington’s biography: a betting debt had almost ruined the duke early in his career, and by virtue of his vow to clean up Regency clubland, he became the campaigner for and the progenitor of a more respectable Victorian club culture (Gronow, 11).16

Beyond the pleasures of smoking and tame gaming, the investment in and commitment to gentlemanly conduct, courtesy, and civility is apparent most immediately in the very proliferation of rules, regulations, protocols, and by-laws that Vi...