![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Era of the

Atlantic Slave Trade

FOR THE PURPOSES OF THIS STUDY, the period following the criminalization of the Atlantic slave trade in the early nineteenth century is the narrative present. This period is characterized by several major transformations, but these nineteenth-century manifestations were shaped, constrained, and guided by African societies and individuals who exhibited a remarkable connection with their past. Moreover, the societies and states of both regions had emerged from a complex history of settlement, migration, social and political development, and cultural exchange with neighboring peoples. Both the Gold Coast and Senegal had been on the periphery of the great empires of the Niger bend, had received waves of settlers from the West African interior, and were connected by trading networks to other parts of the macroregion and even to each other. Senegal, in addition, was on the frontier of the Saharan zone. These African connections would not disappear after the sixteenth century, despite the growing importance of the Atlantic trade.

Nevertheless, the transatlantic slave trade must be recognized as central to the increasing significance of slavery in West African societies and economies, and in this trade, the Gold Coast and Senegal were among the earliest participants. The experiences of the slave trade have been the subject of numerous monographs and countless articles. In West African history, they are sometimes portrayed as the defining feature of the precolonial period, leading to radical social and economic changes. This notion is highly politicized and for the regions under consideration here must be qualified somewhat. While the transatlantic slave trade was a catalyst for sociocultural change within the small seaboard “frontier” areas of Euro-African interaction, its effect became more diffuse the farther one traveled from the coastal zone.

This chapter is not intended as either a comprehensive ethnography or a study of the Atlantic slave trade. Its purpose is threefold: to ascertain the borders of this study in space and time, to establish its comparative structure, and, finally, to examine aspects of the dynamic African societies that formed the setting of this struggle over the issue of slavery.

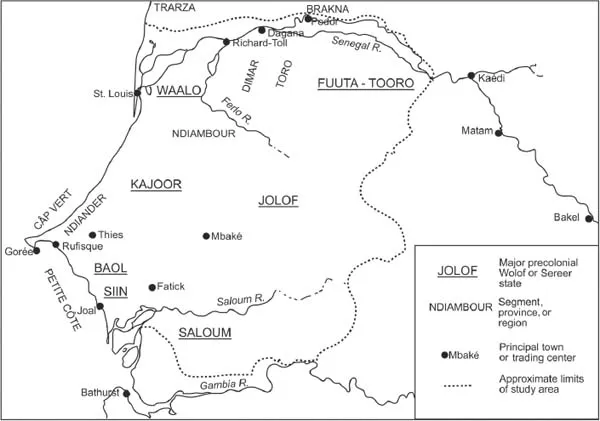

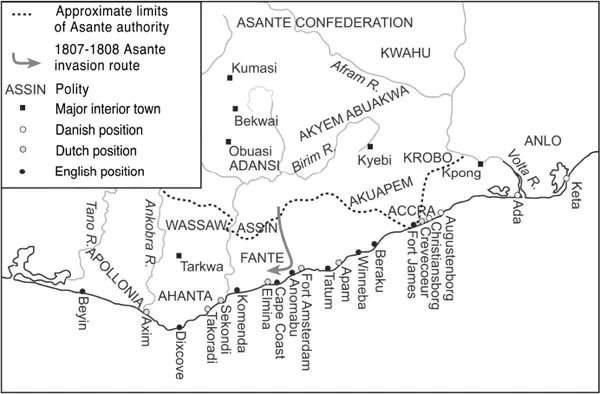

BOUNDARIES

Since the subject of this study is the interaction between specific groups of colonial and African actors, its limits are more defined by human geography than ecology. Thus the regions included in this study can be said to be the Wolof and Sereer states of Senegal and the Akan and Ga-Adangme societies of the Gold Coast. To a greater or lesser degree, the populations of these regions shared a common experience of European intervention in the nineteenth century that exceeded that of regions farther in the interior. This intervention was concentrated on the coast and gradually diminished inland. Coastal towns such as St. Louis, Dakar, Cape Coast, and Accra were centers of Euro-African interaction, whereas large interior states such as Akyem Abuakwa and Jolof maintained a more indirect association with events on the coast until late in the century. States farther removed from the coast and European influence—especially Asante and Fuuta Tooro—had long-established and dynamic relationships with coastal states, but had distinct experiences during the nineteenth century and are not included in this study.

These boundaries are not rigid. During the period in focus, frontiers of colonial expansion and borders between African states shifted. Moreover, ethnicity and state do not necessarily equate, and both subjugated and semiautonomous ethnic minorities existed within the territories claimed by organized states. Finally, the balance of power between competing European powers did not completely resolve itself until late in the nineteenth century.

Ecologically, both regions were affected by the distinct ecological banding that characterizes the environment of West Africa. By 1850 the Senegal River delta was firmly within the arid Sahelian zone. The southern bank of the river during this period constituted the northern boundary of the Wolof state of Waalo. Cultivation, mostly of sorghum and millet, was largely limited to the river’s banks, as the preceding centuries had seen the advance of the Sahara and the transition of the area surrounding the lower Senegal to pastoral rather than agricultural use.1 South of the river, the territory of the Wolof-led states of Kaajor, Baol, and to a lesser extent the interior state of Jolof transitioned gradually to a more fertile landscape until, in the far south, the population of the Sereer states of Siin and Saalum inhabited a wetter complex of river deltas and forests. From west to east there was also an ecological transition. The westernmost point of Senegal was the collection of Wolof-speaking Lebu fishing and farming villages of the Câp Vert Peninsula, while in the east there lay the dry basin of the Ferlo, which is outside the boundaries of this study.

In contrast, the Gold Coast is a hilly and fertile region falling well within the band of forest stretching across the south of the West African bulge. Both the fertile coastal plain and the hills of the Akuapem-Togo Range supported extensive yam and plantain cultivation. An especially wide coastal plain in the eastern third of the region was thick with Ga-Adangme settlements, but aside from the Ewe people of the Voltaic basin, the region was dominated by Akan-speaking polities.

PRECOLONIAL POLITICAL ELITES IN WESTERN SENEGAL

Within both the Senegalese and Gold Coast populations, ethnic and lineage identification were separate from citizenship in a state. This differentiation was more marked, however, in Senegal. In the two large Sereer polities, the state was controlled by dominant Mandinka lineages, the gelowar, who had arrived as outriders of the Mali Empire in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.2 The aristocracy of the states to the north were Wolof, like the majority of their inhabitants. In both regions, however, a significant amount of power lay with the lineage patriarchs, or jambur. The jambur wielded considerable power with the commoners through their position in the kinship system, their control over land, and their ability to recruit soldiers from among their lineage. In Siin and Saalum, at least, their rights were even enshrined in state constitutions. While aristocratic families consistently attempted to attract the jambur as clients, the power of the jambur was in fact augmented by the arrival of Islam, which by the nineteenth century had won converts throughout the Wolof region. Muslims tended to occupy their own villages led by sëriñ-làmb, or titled marabouts—religious officials whose political position roughly equaled that of the jambur.3 The result, by the nineteenth century, was a patchwork of territory under the control of various groups—semiautonomous Muslim communities, ethnic minorities, and aristocratic lineages.

MAP 1.1

The Wolof and Sereer States of Senegal, c. 1800

The power of the aristocracies was largely military. They provided security to the agricultural and pastoralist villages in return for taxes. Aristocratic families succeeded to the throne through a system of patronage, and such patronage was costly. At the top of the aristocracy were the garmi and lingeer, members of aristocratic lineages eligible to provide rulers.4 However, raiding protected villages was self-defeating, since it alienated the jambur. As a result, the military aristocracies augmented their wealth through external raids and wars, the result of which was not only looting, but also capturing and enslaving individuals.5

For Waalo this process of class stratification was even further complicated by the spread, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, of Hassani Arab populations down to the northern bank of the Senegal River. These groups, particularly the Trarza emiral family, were structured much like the Wolof aristocracy in that their means of survival was exacting tribute or pillaging local communities. The climax of the Hassani expansion came in a 1775 offensive that left many north-bank Wolof villages under Trarza control, while raids across the river produced large numbers of slaves both for Trarza slave villages and for export across the Sahara.6

PRECOLONIAL POLITICAL ELITES IN THE GOLD COAST

The Akan migration was a pivotal event in the history of the Gold Coast.7 The immigrants absorbed a number of preexisting groups while only a few, such as the Ga-Adangme of the Accra coastal plain and mountains of Krobo, remained independent. Within the numerous Akan polities that emerged from this process, two notable sets of sociopolitical institutions emerged. The first were mmusuatow (sing. abusua)—matrilineal kin groups—which were the principal organizing units for trade, ritual, and labor. These lineage affiliations were central to organizing the labor needed to clear the dense brush of the interior, and they controlled inheritance, land tenure, and succession. The second was the development of obirempon or oblempon stools, or thrones, often linked to entrepreneurs who settled new areas with the aid of clients and slaves or to merchants made wealthy through the expanding coastal trade.8 Members of a few elite abusua lineages, together with the obirempon, made up the ohene (chiefly) class. However, commoners could gain authority through positions in the patrilineal, populist asafo militia and fraternal companies that began to appear in the Akan states in the seventeenth century.

The normative political model for the Akan polities was one of paramount chieftains supported by a council of chiefly officeholders representing important lineages, as well as division heads with territorial and ritual responsibilities.9 Nevertheless, eighteenth- and nineteenth-century sources suggest that this description disguises a wide diversity of institutions and techniques. Henry Meredith, for example, noted that “the government along the coast partakes of various forms. At Apollonia it is monarchical and absolute. In the Ahanta country it is a kind of aristocracy. In the Fantee country, and as far as Accra, it is composed of a strange number of forms; in some places it is vested in particular persons, and in other places lodged in the hands of the community.”10

MAP 1.2

Political Divisions of the Gold Coast, Showing Asante and European Positions, c. 1807

Often, paramount stools could be contested by a broad category of claimants, with several eligible lineages, both matrilineal and in rare cases patrilineal, competing for power.11 Moreover, the limits and authority of governments were constantly evolving as states expanded. Autochthonous populations such as the Guan-speaking villages of the Akuapem Hills were slowly being brought under state control, necessitating political flexibility in that state.12 Similarly, in the eighteenth century, several states in the interior—Akwamu, Denkyira, Wassa, Akyem Abuakwa, and Asante, especially—underwent a process of bureaucratic development to deal with their expanding borders. By contrast, most coastal polities such as the several paramountcies of the Fante remained quite small and based on a single urban center.13 The Ga-Adangme populations of the coast adhered to a similar model which, however, followed a generally patrilineal system for determining succession, and which in the mid-eighteenth century came under the flag of an expansionist Asante state.

Throughout the nineteenth century, Asante expansionism was also a political reality for all the peoples of the Gold Coast. Assin was an early acquisition of the Asante, and states of the western interior—including Wassaw, Assin, and Aowin—had been occupied in the mid-eighteenth century, although Wassaw opportunistically joined anti-Asante coalitions in the 1730s and ...