![]()

Chapter 1

“Building the New Fatherland,

We Create the New Woman”

Gender Politics in Sandinista Nicaragua

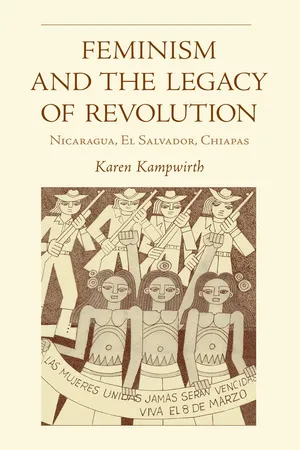

THE GUERRILLA WAR that ushered in the Sandinista revolution (1979–90) was to mark that revolution in profound—and contradictory—ways. One image from the guerrilla period that would be repeated over and over during the decade of revolution nicely captured the gendered legacy of the guerrilla struggle. The idealized Sandinista woman was a mother. A young woman, she grinned while holding a nursing infant; over her shoulder a rifle was slung. Originally a photograph, the image of the nursing guerrilla was reproduced in many forms, including public murals, postcards, and the official poster that commemorated the tenth anniversary of the revolution. That this image was so widely reproduced throughout the revolution is a testimony to its symbolic importance. It captured both the extent and the limits of the Sandinistas’ feminism, as seen through their own eyes.

In this revolutionary image, the nursing mother was armed and powerful. But she was also, apparently, a single mother. No man helped tend to the infant and, in fact, images of men and infants were few and far between in revolutionary iconography, both in Nicaragua and elsewhere (Molyneux 1984, 77). Through the revolution that the image promised, women’s rights and responsibilities were to be extended in significant ways. Indeed, they often were. But the transformation of gender is necessarily the transformation of a relationship. That relationship, including men’s roles, was less often challenged. This near automatic understanding of gender transformation is implied in the name of this chapter, which I took from a phrase that figured prominently in Sandinista discourse during the early eighties.1 Without directly challenging men’s roles, womanhood would be transformed simply by extending the revolution.

While the image of the nursing guerrilla is an image of empowered maternity, it is also, of course, an image of war. Even after the guerrilla struggle, warfare would continue to mark the revolution, often to the detriment of feminist organizing. Guerrilla organizations, like the Sandinista Front that the smiling woman belonged to, are hierarchical by necessity. This may be especially the case for a guerrilla organization like the FSLN that utilizes a mass mobilization strategy and therefore has many thousands of followers who must be organized in some way. The Sandinista guerrillas could have never hoped to overthrow the dictatorship without extremely good coordination. Coordination, in turn, entailed secrecy, verticalism, unquestioning obedience to authority. While the Sandinista project was a democratizing one, it was also a project that was born of a guerrilla organization that was hardly democratic.

So the lessons that were internalized in the guerrilla struggle, and that were reflected in the image of the nursing guerrilla, were laden with tensions. In the guerrilla struggle of the sixties and seventies, thousands of women gained the opportunity to break the constraints of their traditional roles. It was also in the guerrilla struggle that many women who were to go on to be feminist activists first gained the skills and consciousness that made their later activism a real possibility. In some sense the guerrilla war opened opportunities for many women that would have remained closed had the dictatorship entered a third generation, as it almost surely would have done if not for the FSLN. And Sandinismo would forever mark Nicaraguan feminism, even in the case of women who were to reject their formal ties to the party. “Without the revolutionary movement, feminism would undoubtedly still be the province of a privileged few” (Chinchilla 1997, 209).

At the same time, old lessons are hard to forget, especially in times of stress. It is true that Sandinista leaders presented significant evidence, in deeds as well as words, of their commitment to democratization.2 That democratizing project often even extended to gender relations.3 But evidence of their commitment to democratizing gender was most forcefully presented in the best of times, especially in the first two years of the revolution, before the right-wing contras began their attacks on the Sandinistas and anyone who might support them. Once the contra war had begun in full force, the leadership was often tempted to fall back on the lessons it had learned in the guerrilla struggle. Those lessons included the importance of avoiding controversy within revolutionary ranks and of controlling any dissent that might arise. Neither lesson boded well for feminists.

After Somoza, 1979–82

As the Sandinistas—women and men—triumphantly entered Managua on July 19, 1979, waving the rifles with which they had overthrown the hated Somoza dictatorship, it was clear that the balance of power in Nicaragua would never be the same. Even if the Sandinista leadership had wanted to leave gender relations untouched, that would have been nearly impossible. Far too many women had been mobilized in the guerrilla struggle to make a return to the “good old days” easy. But that was never the intention of the Sandinista leadership. From as early as a decade before the overthrow of Somoza, the FSLN had promised that the emancipation of women would be one of the goals of the revolution.4 And so it was.

Starting in July 1979 the state was transformed in multiple ways, many of which directly affected gender relations. That transformation involved legal reform, the expansion of access to education, the nationalization of health care, and the creation of a wide range of state services, such as day care centers, that opened new opportunities for women. Revising the laws that regulated gender relations was one of the very first things the new revolutionary government did.5 No doubt this was because changing laws was fairly easy. Also, in the initial excitement of the revolution, many hoped that new laws would rapidly make a new society. Ana María, who would become director of Nicaragua’s first state women’s institute, the Women’s Legal Office, explained: “At the founding of the revolution I thought everything was going to be different, I saw it as a utopia. . . . I thought that by changing the laws they were going to change the people” (interview, May 7, 1991).

On July 20, 1979, the day after they took power, the Sandinista leaders decreed the Law of the Means of Communication, prohibiting the use of women as sex objects in advertising (Junta de Gobierno 1984, 25; Murguialday 1990, 126). On that same day, they passed a law that “established penalties so as to suppress white slavery and prostitution” (Junta de Gobierno 1984, 22), which was followed a few months later by voluntary alternative-job training programs for prostitutes, offered by the Social Service Ministry (Junta de Gobierno 1984, 22). In 1981 the Breast Feeding Promotion Law directed the Ministry of Health to promote breast feeding at the same time as it forbade the advertisement of baby bottles and formula (Lacayo and Lacayo 1981, 286–87; Murguialday 1990, 126 ). All these legal reforms contained a dual agenda: to improve women’s status and to limit what the Sandinistas saw as capitalist excesses.

Another category of laws tried to eliminate insidious distinctions between the children of married and unmarried people. For instance, social security made people in common-law marriages eligible for benefits (Murguialday 1990, 126–27). The 1980 adoption law made it possible for single women or men to adopt without having to be part of a couple (Collinson 1990, 111; Murguialday 1990, 126). Here too, reforms contained a clear class content as well as a gender content since the poor were far less likely to legally marry than rich or middle-class Nicaraguans.

Finally, a third category of laws was directly aimed at transforming gender relations. The Statute of Rights and Guarantees of August 1979 declared the “absolute equality of rights and responsibilities between men and women,” banned differential privileges based on legitimacy, and included the right to investigate paternity (Stephens 1988, 153–54). A new labor code forbade the Somoza-era practice of the “family wage,” under which the male heads of rural families had received a single wage for the work of their wives and children (Murguialday 1990, 127). And the Law of Relations between Mother, Father, and Children eliminated the Somoza-era concept of absolute paternal authority (patria potestad), in favor of shared custody. Mothers and fathers were to have equal rights to, and equal responsibilities toward, their children, except in the case of young children. Mothers would automatically receive custody of children under seven while the preferences of children over seven would be considered (Collinson 1990, 111; Murguialday 1990, 128; Stephens 1988, 156).

The last piece of gender legislation in the early years of the revolution was the 1982 Nurturing Law.6 Unlike earlier legislation that also proclaimed the shared responsibilities of family members, this law included mechanisms to put those ideals into practice, introducing equal pay for equal work, state pensions, and the right of nursing mothers to take an hour off work every day to breastfeed (Murguialday 1990, 128).

If it had only been for those provisions, the law would no doubt have passed. But the Nurturing Law also required that all household members—including men—participate in housework and childcare. Divorced or separated women who could not work outside the home (for reasons of health or age) would be entitled to a pension to be provided by the former partner. According to the law, adults were responsible for their children while children and grandchildren were to provide for parents and grandparents who were too old or sick to work (Collinson 1990, 111–12; INSSBI n.d., 10; Murguialday 1990, 128–31). This proposal was described as the “most polemical of the many laws that had been proposed at that time” (Murguialday 1990, 130). It never went into effect, although it was approved by the Council of State, because the Governing Junta would not ratify it. The failure of the Nurturing Law marked the end of Sandinista gender lawmaking until the late eighties.

The reason that was most commonly given for the end of the first period of gender lawmaking was the beginning of the contra war. The same women who had been promoting family law reforms agreed with the Sandinista leadership that campaigning to democratize gender and generational relations could be divisive and, ultimately, threatening to the war effort (Stephens 1988, 158). Defending the revolutionary project that had made legal reform possible was given priority over short-term reforms that might undermine the long-term health of the revolution.

No doubt the concern over the war was one of the reasons, probably even the central reason, for ending the early period of legal reform. But another reason may have been the Sandinista leaders’ discomfort in the face of increasingly radical, even feminist, demands from their own base. As Governing Junta member (and later president) Daniel Ortega tried to explain, “The social conditions to put these ordinances into effect did not exist” (quoted in Murguialday 1990, 130). Interestingly, Ortega did not raise such objections regarding other potentially divisive issues, like land reform.7

So the legal reforms of gender roles had their limits, either due to the war or the leadership’s concerns about the development of feminism in the revolution, or both. They were also limited in that law tends to be the preserve of the elite, though that was less true than it usually is, since many of those laws were crafted through mass consultations. Nonetheless, the real revolution in public policy did not occur in the law. Instead, most Nicaraguans pointed to educational and health reforms as the central accomplishments of the Sandinistas. Under Somoza, illiteracy rates were high for everyone, especially for women. While 16 percent of urban men were illiterate, 22 percent of urban women could not read or write. The situation was worse in the countryside: there 64 percent of men and 67 percent of women were illiterate (Stromquist 1992, 27). One of the Sandinistas’ earliest goals was to overturn the dictatorship of illiteracy, just as they had overturned the dictatorship of the Somoza family.

Years later, the literacy crusade of 1980 is probably the single most remembered event of the revolutionary decade. And with good reason; such collective social battles are rare occurrences in human history. Through the literacy crusade, tens of thousands volunteered for five months to teach their fellow Nicaraguans to read. The crusade disproportionately helped women since more women than men had been illiterate to begin with. Moreover, the crusade often brought female students together with female teachers: 60 percent of the teachers were female (Collinson 1990, 124). Over four hundred thousand people would learn to read and write during the crusade, reducing Nicaragua’s illiteracy rate from over 50 percent to slightly under 13 percent (Brandt 1985, 328; Hirshon 1983, 215; MED 1984, xvii).

But it would be an exaggeration to claim that, because more women than men participated in the crusade, it was therefore a feminist crusade. In fact, one might argue that an opportunity to integrate the transformation of gender relations into one of the Sandinistas’ most important public acts was largely missed. The textbook that was used for the crusade, Dawn of the People, was highly nationalistic, featuring Sandino in the first lesson and emphasizing the class content of the revolution much more than its gender content.

Nonetheless, women were not completely forgotten. Lesson 19 linked women’s liberation to revolution through its key phrase, “Women have always been exploited. The revolution makes possible her liberation” (Barndt 1985, 326–27; Hirshon 1983, 51, 67).8 This lesson echoed the revolutionary slogan, “Building the new fatherland, we create the new woman.” Both identified the transformation of women’s roles as part of the Sandinista agenda and at the same time suggested that the transformation of women’s roles would be the automatic result of other revolutionary policies.

The literacy crusade did have an impact on gender relations, but that impact was fundamentally an outgrowth of the experience of being a teacher or student rather than a response to the ideas that were promoted through the crusade. Many of those who went on to become feminist activists, especially those who had not been active in the anti-Somoza struggle, pointed to their participation in the crusade as a turning point, the time when they were introduced to a world beyond the constraints of their homes. When I asked América, who at the time of the interview directed the women’s secretariat in ANDEN (the Sandinista teacher’s union), about her first political experience, she explained that she first became politically involved upon completing high school in 1980: “That was the beginning of my teaching career and also the beginning of my political career. For the first time I came to know the countryside. And from that point on I integrated myself into revolutionary life” (interview, January 22, 1997).

If, in the collective Nicaraguan memory, the literacy crusade is the most important event of the early Sandinista years, then the reform of health care is a very close second. The reasons for that are similar to the reasons for the reverence with which the literacy crusade is remembered. To begin with, health care under the Somozas was miserable,9 so the improvements of the early eighties were profound. Moreover, the reform of health care is remembered with near equal reverence because those reforms were collective. The revolutionaries placed a high priority on reforming health care, eliminating fees for hospital and clinic visits, and mobilizing the population for preventive health brigades. Through these brigades, children were immunized, latrines and clinics were built, and the population was educated in basic disease prevention (Bossert 1985, 352–53). The campaigns were quite effective. For example, the vaccination campaign nearly eradicated polio and greatly reduced levels of other infectious diseases. While there were only forty-three health clinics in 1978, there were 532 by 1983 (Pérez-Alemán 1992, 241). And women participated in this transformation of the health of the Nicaraguan people to an even greater extent than in the literacy crusade. A full 75 percent of the volunteers in the health brigades of the early eighties were women (Collinson 1990, 96–97).

In the early eighties, thousands of women, often very young women, were mobilized by the Sandinista government for a variety of purposes: to teach others to read, to immunize children, to harvest coffee, to guard their neighborhoods at night. Those campaigns played a critical, if not always planned, role in the challenge to traditional authority that was the revolution. In response to my question about the impact of the revolution on family life, Dinora emphasized the impact of this mass mobilization, especially in the literacy campaign: “Nearly everybody went: in Managua there were no young people left. We went off on our own, we lived independently for five months. All those young people were different when they returned. Their parents felt that up to a certain point their dominance over them was no longer great. After that the coffee-picking brigades came along; the ones who benefited most from them were women. Already women’s mentality had changed. That benefited women a lot. It’s a very big change, in reality” (interview, April 1991). Dinora’s uncle Sergio also linked changes in family life with mobilization into Sandinista activities: “The revolution changed everything. . . . There was a change in parents, in children. Their children went to pick coffee, to the mountains, they went far away. And we felt good about this change. Nobody was forced to go pick cotton, to teach literacy. . . . [There was] freedom for women in the work. That was a tremendous change because they went to work with men. Men and women working. It’s a tremendous change in family life” (interview, April 1991).

Opponents of the revolut...