![]()

one

Reading the Christmas Gift Book

The approach of Christmas shows itself on our Library Table in every fantasy of gold and colour—covering every sort of poetry and illustration with binding worthy of the literary and pictorial artist.

Athenaeum1

In 1846, a new form of gift book appeared on the Christmas market when James Burns published Poems and Pictures: A Collection of Ballads, Songs, and Other Poems Illustrated by English Artists.2 The title is instructive. Like the contemporary Illustrated London News, launched only four years earlier, Burns’s anthology foregrounds the relative equality of pen and pencil, verbal art and visual art.3 Presented by the publisher simply as “A Collection of Ballads, Songs, and Other Poems,” the poetry appears to be drawn from a rich cultural storehouse without the mediation of author or editor. If the literary contents represent a shared inheritance of ballads, songs, and poems, the pictures derive value from their connection to contemporary ways of making national art: they are “by English artists.”

When we open the green and gilt ornamental covers, we notice a similar balancing of verbal and visual arts, with a wood-engraved frontispiece followed by a decorative title page. Every subsequent page of text sets the poetic letterpress within wood-engraved borders or beside ornamented margins. Intermittently, the verses appear with a wood-engraved illustration that takes up at least half the textual page. The image is typically set at the head or tail of the poem and represents scenes and figures from the poetic text. While the book as a whole presents the graphic ornaments as integral units of the printed page, its bibliographic apparatus draws special attention to the figural illustrations. Two tables of contents separate verbal and visual items into distinct lists. At the same time, the contents pages connect the differentiated lists semantically through the shared subjects and graphically through the woodcut borders and decorations present on each textual page.

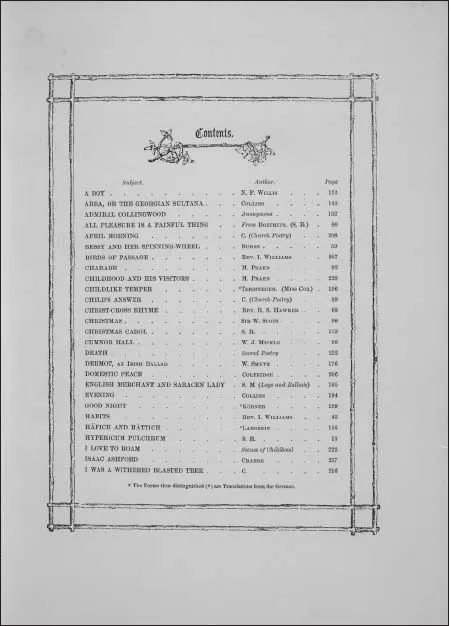

Like the title’s pairing of Poems and Pictures, the separate contents tables announce the relative parity of verbal and visual subjects in the book while also constructing a reader interested in both pictures and words. Organized alphabetically by “subject” (that is, title) with no apparent classification of period, style, genre, or theme, the poetic contents represent a wide range of popular poetry, with verses taken from the periodical press, church liturgy, and authors’ collections (fig. 1.1). Beside each subject/title, another column identifies the author’s name. Because the subjects appear alphabetically, works by individual poets are not grouped together but are instead distributed throughout the contents.

Figure 1.1 Contents page, Poems and Pictures (Sampson Low, 1860). The Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto.

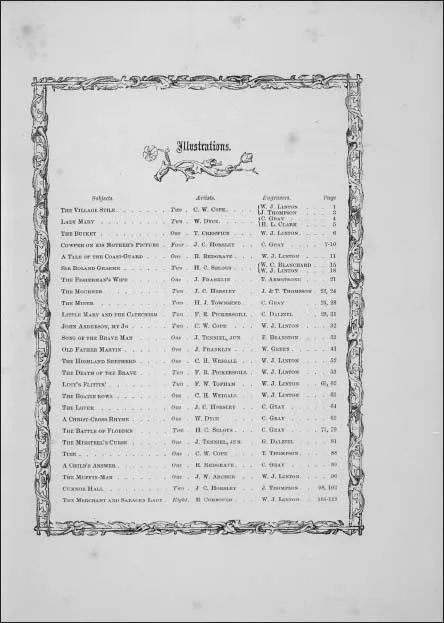

When we turn to the illustrative contents, an alternative organizational structure for the book presents itself (fig. 1.2). Unlike the verses, the artistic contents are listed sequentially, in the order each subject appears in the book. Parallel columns indicate the number of illustrations associated with the subject/title and identify two authors for each picture: the artist who designed the drawing and the engraver who cut the woodblock. To identify the author who composed the subject as a poetic text, one would need to turn back to the verbal contents page. Because the poet is not listed as the originator of the subject that the artist draws and the engraver cuts, the book accords neither priority nor superiority to the poetry. In the composite art of the illustrated gift book, the authority of the author gives way to the imperative of the book’s material and social systems of making and using.

Figure 1.2 Illustrations page for Poems and Pictures (Sampson Low, 1860). The Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto.

These distinct methods of organizing literary and artistic contents acknowledge not only the book’s multiple makers but also its mobile users: readers are able to enter its pages at various points for a variety of purposes. Using the alphabetic guide of subjects, a reader could locate poems connected with Christmas or childhood, or search out a favorite title such as “King Arthur’s Last Tournament,” by Sir Walter Scott. If the reader is keen about particular poets, the author list could be searched for their names. Browsing the author column, a reader could also decide to read poems by women (this would not take long) or focus on the anonymous verses taken from Church Poetry (this would take considerably more time, especially if the reader then decided to move on to all the poetry by “Reverend” poets, including Isaac Williams and Henry Alford).

Alternatively, a reader could begin with the pictorial contents and choose to read only the fifty-one poems accompanied by pictures. A reader might even elect to skip the poetry entirely and concentrate solely on the illustrations, one day choosing to look at all the pictures by Clarkson Stanfield and another, perhaps, comparing the engravings made by W. J. Linton to those made by G. Dalziel or T. Armstrong.

The architecture of Poems and Pictures built its readers into its gilt-edged pages, tacitly giving them a degree of authority not accorded to any single individual on cover or title page. Associated with a publisher rather than either author or editor, Burns’s Poems and Pictures asserts, in its title, contents, and material form, that the gift book is a cultural commodity, mass-produced through the technologies of the publishing industry and its divisions of labor for a mobile reader keen to select her own collection of poems and pictures.

The combination of literary and pictorial content had proved to be a winning one in the popular annuals published for Christmas markets from the 1820s to the 1850s. However, with the emergence of wood engraving in the 1840s as an efficient and affordable method of reproducing images, the bibliographic format and contents of the annuals began to look old-fashioned. Poems and Pictures established the new vehicular form for the illustrated gift book this study addresses. As John Buchanan-Brown demonstrates persuasively in Early Victorian Illustrated Books, the steel-engraved annuals had become “an outworn tradition” when Burns’s Poems and Pictures emerged “to establish the new pattern of Christmas gift book, one of the most important genres for the Sixties’ illustrators” (134–35). Because both the early Victorian annuals and the characteristic sixties publications were Christmas gift books encasing poetry and pictures in ornamental covers, it is worth taking a moment to consider what distinguishes them.

The new style of gift book combined poetry by standard or popular authors with original wood-engraved illustrations conceived and produced specifically for mass reproduction. Each picture in the new style of gift book was uniquely designed for the printed page and appeared in the familiar vernacular of wood engraving, the graphic language of the illustrated press. In contrast, each picture in the older style of gift book, the annual, was not uniquely designed for the book in which it appeared. Rather, it was a copy of a preexisting artwork owned by a wealthy collector or institution. These large, steel-engraved reproductions of existing academy paintings—picturesque landscapes and ruins, portraits of fashionable ladies, and sentimental genre paintings—were not illustrations. Instead, they were illustrated by literature composed in response to them. In addition to these ekphrastic works, the linguistic contents of annuals also contained a miscellany of other writings, both poetry and prose.

Paula Feldman notes the significance of the annuals in allowing “ordinary people to own high quality reproductions of significant works of art” (Keepsake, 7). If annuals gave access to fine art in the form of reproduced paintings, the wood-engraved poetic gift book permitted ownership of an original artwork that straddled the borders of “high” art and mass production. As I argue in greater depth below, the new gift books of the sixties allowed ordinary people to own copies of prints for which no originals existed. The wood-engraved art of the gift book was not a shadowy, tonal reproduction of a unique easel painting, reduced to accommodate codex form. On the contrary, it was an exact-size graphic art expressed in black, inked lines on white paper. The wood-engraved illustration was a book art designed by a living British artist for the express purpose of being printed in relief with letterpress, using the most advanced technologies of the age. Combining hand and machine, art and craft, the wood-engraved image was, in fact, a popular art form unique to the age of nineteenth-century reproduction.

Picturing Poetry in “Cuts”

The significance of the illustrated poetic gift book as a popular publishing phenomenon linked to contemporary visual culture must be understood in the context of its modes of production. When the wood-engraving industry emerged in the 1830s and 1840s as the principal method of mass-producing images, a new artistic form was made possible because the reproductive technology allowed the picture to be set up and printed with the type.4 Because the engraver’s woodblock and the compositor’s leads used the same relief process, they could be printed together with a steam-powered press on ordinary paper, thus reducing costs and enabling large print runs. This common printing process also permitted a new proximity of picture and word on the page and a visual similarity in inked effect, as typography and design could, theoretically at least, be of similar weight. The method was pioneered by Thomas Bewick, who altered forever the rough linear woodcut of past centuries by using the end-grain of boxwood (or other similarly hard wood) instead of the side-grain of a softer fruitwood. The hardness of the end-grain permitted the use of a finer and more delicate graver and the nuanced representation of light and shade. Earlier woodcut artists of the popular chapbooks and broadsides treated the plank as a white space on which black lines were cut with a knife. Bewick revolutionized the art of relief engraving by treating the block as “a black void out of which the subject appears in a varying range of grey tones with pure white for the lightest parts.”5

Bewick developed his method in the early nineteenth century, but its commercial possibilities were not fully realized until the technologies of mass production and demands of increased literacy revived the wood-engraving industry in the 1830s and 1840s. The launch of Charles Knight’s Penny Magazine in 1832 and, a decade later, the first illustrated weekly, the Illustrated London News, revolutionized print culture and the reading experience of the popular audience. These mass-produced periodicals and the books that followed them, however, could not achieve the requisite production levels by following Bewick’s artisanal methods. Bewick drew his design on the wood, cut the block himself, and oversaw the printing process in his own shop. In contrast, the wood-engraved pictures in the periodicals and books of the second half of the nineteenth century were produced in an industrialized economy characterized by the division of labor.

The pressing deadlines of a periodical required that “large cuts” be divided into separate woodblocks and given to different engravers, the whole being reunited at press time. Although engravers typically worked alone on a single illustration in book projects, this did not necessarily lead to increased unity in the final product. The practice of using a variety of artists and engravers—including engravers from different firms—for the same volume often resulted in a variety of styles and skills. A gift book such as Edward Moxon’s 1857 illustrated edition of Tennyson’s Poems (discussed in chapter 2), for example, was the work of multiple artists and craftspeople, each aware only of their own labor and ignorant of the whole—an assembly-line approach that made mass cultural production possible and the products accessible but had a deleterious effect on overall design and artistic unity.

This mode of production resulted in books whose repetitive sameness and montage character might be seen as analogous to the mass-media products of the twentieth-century culture industry critiqued by Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno. Certainly, the standardized effects of the Victorian culture industry’s methods were not lost on nineteenth-century observers. However, the Christmas book also evoked some national pride in Britain’s industrial power. Indeed, the Christmas book represented a recognizable British brand. As one contemporary reviewer noted, “Christmas books are made, not written…. It is no discredit to a Christmas book that it is manufactured, got up to order—size, price, and contents being determined by the state of the market…. They are just as recognized, and perhaps as legitimate, a branch of national industry as Paris bronzes or Birmingham buttons. And as in one case, so in the other, every rank of the skilled workman finds his employment in the manufacture of this literature of the magazine and periodical and Christmas book sort” (SR, Nov. 24, 1866, 653).

Although there are a few exceptions—William Allingham, for instance, proposed the illustrated edition of The Music Master to Routledge—the typical gift book was not the tangible outcome of an artist’s or author’s inspiration but instead was a commodity conceived in the office of a publisher or engraver. As we shall see in chapter 3, if the publisher or engraver were preparing an anthology, he might also act as editor, choosing and arranging the poetical selections himself or commissioning poets to write on a set theme. The poetic contents might also be focused on the writings of a particular author: for example, on the collected works of a popular living poet such as Jean Ingelow (discussed in chapter 4) or on a single narrative poem by Tennyson, such as Enoch Arden or The Princess (discussed in chapter 5). In these cases, the publisher would determine when the writer’s popularity was sufficient to command the kind of sales that would offset the expenses of illustration and calculate the number of images, the size of the print run, and the time of release. Generally, this process began in winter or spring for an expected publication date between October and December for the Christmas sales season.6

The publisher would then set about commissioning the necessary artist(s) and engraver(s); sometimes, the publisher would subcontract an engraving firm to supervise all arrangements relating to the book’s illustrative contents. Once the artists had been confirmed, they typically had a free hand in selecting their own pictorial subjects. Where necessary, the publisher would also supply the artist with copy text. As I discuss in chapter 5, Moxon appears to have provided Daniel Maclise with the most recent edition of The Princess when he gave Maclise the commission, just as Strahan provided Arthur Hughes with Tennyson’s lyrics for The Window. Occasionally, as we shall see in chapter 3, an engraving company such as the Dalziels’ might take on responsibility for the entire contents and produce gift books that were artist- rather than author-focused. In such cases, the Dalziels would commission an artist (for example, Myles Birket Foster or Arthur Boyd Houghton) to produce a set number of pictures on a particular theme, then commission a poet or poets to write a page of verse to accompany each full-page plate. In such cases, the Dalziels supplied the poets with proofs of the prints so they could carry out their commissions.

Working in his own studio, the artist would cover the end of the boxwood in Chinese white, creating a smooth, blank surface on which he then drew his design in reverse. Dante Gabriel Rossetti was so unfamiliar with the reproductive process that he neglected to reverse his first design on wood and had to redraw “The Maids of Elfen-Mere” for William Allingham’s Music Master painstakingly on a new block (Rossetti, Correspondence, 1:388) (fig. 1.3). Because the end pieces of boxwood were small—generally no more than about three inches by five inches—the drawing required extremely fine work by the artist and the engravers. In the early 1860s, new technological developments enabled the photographic transfer of the artist’s design to the woodblock. As I discuss in more detail in chapter 5, this innovation allowed the artist to draw direct rather than in reverse and to produce his composition on paper in a larger scale, as it could be reduced when transferred. Before this new technology was harnessed to the wood-engraving process, the artist’s original drawing was lost when the engraver cut the penciled lines. In an effort to preserve a record of the design, artists sometimes photographed the block before giving it to the engraver, but apart from their preliminary studies, there was no “original.”7 Thus the wood-engraved image was simultaneously unique and multiple.

Another innovation of the sixties was the new requirement of facsimile engraving. Prior to about 1855, wood engravers were not expected to cut each line drawn by the artist but rather to interpret the composition for reproduction. The illustrators of the sixties, however, demanded facsimile engraving (Houfe, Dictionary, 109). Engravers used magnifying glasses and extremely fine cutting tools to reproduce the artist’s drawing as an exact copy of the original, rather than a translation of it. Although a printed wood eng...