![]()

Part I

Gateways to Africa

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Egypt and North Africa

Peter von Sivers

In May 1989, an eighteen-year-old woolcarder set fire to the Husayn Mosque in Cairo. The incident was written up in an Islamic newspaper by a journalist who deplored the act. The article began by asking why this young man would travel from his northern suburb all the way downtown to pray in a mausoleum-mosque—a place where, because of his stance on saint veneration, he believed prayer would be invalid; could he not instead have gone to any of the many mosques of Cairo that did not have tombs? In the remainder of the article, the journalist presents authoritative opinions by establishment figures on the specific requirements of order and decorum during mausoleum visits and on ordinary Muslims wrongly taking the law into their own hands. The article concluded that the woolcarder’s act was indefensible.1

This incident illustrates a typically modern conflict in northern Africa. A Muslim accepting the teaching of absolute separation between God and his creation literally takes drastic action to end the deeply rooted popular tradition of saint veneration in Egypt. And a believer in the traditionally broad Sunni orthodoxy defends saint veneration, provided it occurs in an orderly fashion according to accepted custom (adab). The conflict is not without precedent in earlier centuries, but it is only today that the two positions are seen as irreconcilable.

This chapter deals with, first, the formation (700–1250 C.E.) and dominance (1250–1800 C.E.) of a broad Sunni orthodoxy as the religion of the majority of the inhabitants of northern Africa; and second, modern efforts at political centralization and a narrowing of orthodox Sunnism, both of which have contributed to the rise of contemporary Islamism (1800 to the present).

The Formation and Dominance of Sunni Orthodoxy (700–1800)

The promotion of a specific religion as orthodoxy by an empire is a relatively late phenomenon in world history. The first to be so promoted was Zoroastrianism, adopted by the Persian Sasanids (224–651 C.E.) as their state religion. Islam, supported by the Arab caliphal dynasties of the Umayyads and Abbasids as the religion of their far-flung empire after their rise in the seventh century C.E., was the most recent. In all cases—be it Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Christianity, or Islam—the endorsed religion was attributed to a founding figure who preceded the empire. These religions went through more or less extended formative phases in the empires before they crystallized into dominant orthodoxies and a variety of heterodoxies that either died out or became marginal.2

Christianity, the state religion of the Roman-Byzantine Empire from the fourth century C.E., was in the last stage of its doctrinal evolution toward imperial orthodoxy when the Arabs occupied Byzantine Syria and Egypt in 634–55. It appears that it was the still unsettled question of a Christian orthodoxy for the Byzantine Empire that inspired the rulers of the new Arab empire to search for their own, independent, religion. Caliph ʿAbd al-Malik (685–705) was the first to leave us an idea of the beginnings of this new religion in the inscriptions of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem (691). He called this new religion “Islam” and proclaimed its superiority over Christianity.3

During the early seventh century, Byzantium had been racked by the controversy between the patriarchs of Constantinople and Alexandria over the orthodox interpretation of Christology. Constantinople advanced the doctrine of Christ’s mysteriously double nature, divine as well as human (the Nicene Creed). Alexandria insisted on the more rational doctrine of God’s single, divine nature descending into the human form of Jesus (Coptic monophysitism). While the emperors vainly sought to impose a compromise formula, the caliphs took advantage of their disarray. “Do not speak of three (gods),” warns one of the inscriptions on the Dome of the Rock, disposing of Christology altogether.4 Islam was presented as the new, superior religion, built on a clear, rational separation between a single, non-Trinitarian God and the world.

Proclaiming a new religion was one thing; turning it into an orthodoxy was another. Inevitably Islam underwent the same process of rancorous divisions as did Christianity before orthodoxy eventually emerged. The rancor began over the nature of the caliphate and its ability to define doctrine. The caliphs interpreted themselves as representatives (caliphs) of God, and said that their decisions, therefore, were divine writ. On the other hand, it was claimed that because the divine word was laid down (probably by the 700s) in scripture, in the Quran, no one was privileged over anyone else to make law; the interpretation of scripture was held, in this view, to be a collective right.

At first the caliphs continued to issue laws and formulate dogma as they saw fit, but in the ninth century the tide turned. Pious critics, claiming to speak for all Muslims, increasingly gained the initiative. What had hitherto been caliphal law now was turned into the alleged precedents (hadiths) established by the prophet Muhammad. Ad hoc dogmas promulgated by the caliphs were replaced by a progressively systematic theology formulated by the critics. By the mid-thirteenth century, the separation between religion and state was complete: the critics, now officially recognized as the autonomous body of “religious scholars” (ʿulamaʾ), controlled dogma and law; the rulers had been demoted to the position of executive organs of religion.5

While the ʿulamaʾ were busy establishing the basics of scriptural orthodoxy, a parallel development was occurring on the level of religious practice. Early evidence comes from what began as a military institution during the period of the Arab conquests—the sentry post (ribat). Such posts—towers, forts, castles—existed by the score in northern Africa, along the Mediterranean coast, and in Anatolia, for protection against Byzantine counterattacks. In the ninth century, many of these posts lost their military purpose and evolved into autonomous religious foundations (waqfs), in conjunction with agricultural enterprises, mosques, and meeting rooms, and supported by alms and gifts. In the ribats, committed Muslims met for Quran recitation and ascetic practices, imitating the prophet Muhammad’s life. (The Quran and the biography of the Prophet became available as scriptures probably in the early 700s and 800s, respectively.) Many were mystics (sufis) and wrote manuals on how to acquire divine knowledge (maʿrifa), or were revered as “friends of God” (walis)—that is, saintly figures whose prayers and rituals for rain, healing, or exorcism were reported as effective and who attracted pilgrims and religious fairs to their ribat.6

As orthodoxy was being hammered out during these early centuries, dissenters essentially had two choices. Either they rejected the authority of caliphs and scholars altogether, a position taken by the so-called Kharijis (“Seceders”), and made the fulfillment of all laws and duties incumbent on Muslims as individuals. Or they deplored the caliphal retreat from law and dogma as a betrayal and labored for the reestablishment of the true caliphate, or “imamate” [(true) leadership], whose holder was held to be divinely empowered. The latter position was taken by the Shiʿis (“partisans” of ʿAli, who is traditionally listed as the fourth caliph). At the center of the Islamic Empire, adherents of both positions were ruthlessly persecuted and they therefore generally mounted their oppositional movements on the periphery.

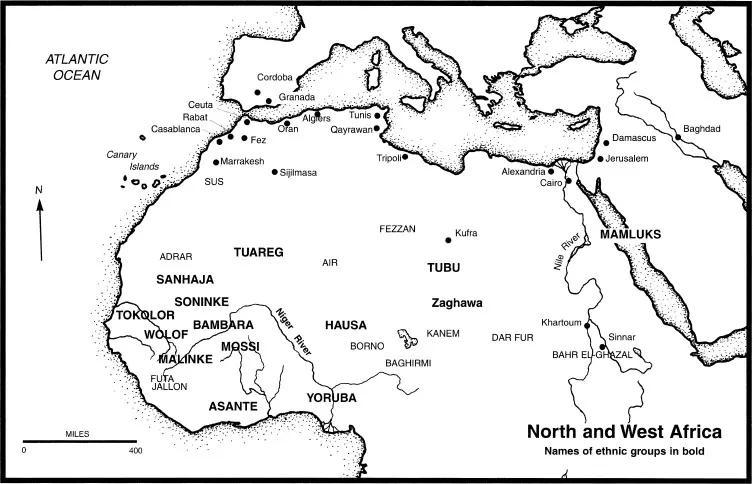

North Africa, or the Maghrib (the “West”—that is, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco) was one such peripheral refuge for dissenters. It was a sparsely inhabited imperial province of limited agricultural resources located on the coastal plains along the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, the adjacent mountains (the Kabylia in eastern Algeria, the Atlas in northern Morocco), and the oasis clusters of the northern Sahara. The steppes of the vast interior high plateau supported only pastoralists. The sedentary, mostly Christian population of indigenous Berbers in Byzantine Tunisia and Morocco (Tangier and Ceuta) had officially surrendered to the Arabs by 711 after half a century of intermittent fighting. The mountain villagers, high-plateau pastoralists, and desert nomads, fiercely devoted to their independence, either avoided the new Arab conquerors or fought them, stirred into action by Khariji refugees from the Arab heartlands.

In the middle of the eighth century, the Khariji refugees and local Berber converts founded a number of small mountain and oasis states that quickly supplemented their limited agricultural resources with camel-borne trans-Saharan trade. Baghdad, the capital of the Abbasid Empire, was in the process of developing into a cosmopolitan cultural and economic center with intensive trade interests in East Africa, India, China, Scandinavia, and the western Mediterranean. Cordoba, the capital of the Spanish Umayyads, was an almost equally impressive rival. The trade in both empires was based on a bimetallic monetary system of gold and silver coins. Most of the gold was obtained from Nubia, on the upper Nile to the south of Egypt, and West Africa, in the region of the upper Niger and Senegal Rivers. Nubia and West Africa were outside the Islamic empire. The merchants were Egyptian Copts and North African Kharijis who traded cloth and copperware for gold, ivory, and slaves. The Kharijis maintained permanent residences as well as mosques in the northern market towns of the Sudanic kingdoms and thus were the first carriers of Islam into West Africa.

As opponents of any strong central political authority, the Kharijis were content with small realms, far removed from the caliphs and religious scholars in Baghdad. By contrast, the Shiʿis favored a return to the original concept of the caliph as the sole representative of God—a concept that was being transformed in emerging Sunni orthodoxy into the caliph-ʿulamaʾ coregency. When their emissaries preached the message of the mahdi to establish a realm of justice, peace, and unity on earth, they clearly had the replacement of the Abbasid caliphate and its clerical scholars in mind.7

But even the Shiʿis had to start their proselytizing far away, in the mountains of Lesser Kabylia in eastern Algeria. There, at the end of the ninth century, a missionary from Iraq converted the Kutama Berber villagers to the cause of the Ismaʿiliyya, a Shiʿi branch devoted to immediate revolutionary action. The missionary Abu ʿAbdallah was part of a worldwide network of missionaries (daʿi, plural duʾat). They carried a religious message in the name of the descendants of Ismaʿil, the eldest son of Jaʾfar the sixth imam of the Shiʿa. Ismaʿil died before his father and his supporters, the more militant among the Shiʿis, rallied around his son Muhammad, and split from the main stream of the Shiʿa.8

In the early 900s, the Kutama Berbers conquered Tunisia from a local dynasty of Abbasid governors. The original missionary relinquished leadership to Ubayd Allah the Mahdi, who had lived in an Ismaʿili center in Syria before he was forced by Abbasid persecution to flee to the Maghrib. Once in power, the first Fatimid caliph began to implement his idea of the utopian realm of justice on earth (909–34). He and his descendants interpreted this to mean no less than the vanquishing of the Abbasid Empire—a feat they in fact almost accomplished. In 969, they conquered Egypt, Syria, and western Arabia; and in 1058/59, a Fatimid general briefly held power in Baghdad. Impressive as these conquests were, however, reality soon fell short of utopia: the justice of the Fatimids was no more equitable than that of the ʿAbbasids. They collected the same heavy taxes from the peasants and confiscated the properties of merchants and officials with the same arbitrariness. Furthermore, in spite of major propaganda and conversion efforts, they never succeeded in supplanting the nascent, but tenacious, Sunni orthodoxy in their empire. When the Fatimids eventually collapsed in 1171, their version of Islam disappeared rapidly from the central Islamic lands.9

Not surprisingly, while Fatimid imperialism was still dangerous it instilled militancy into the rising Sunni orthodoxy. From the mid-eleventh century onward, newly converted ethnic groups—Turks from Central Asia and Berbers from northern Africa—made themselves the champions of nascent Sunnism against the Shiʿis, the Christian Crusaders in Palestine, and the Christian reconquistadores in Spain.

The rural Berbers in northern Africa had barely been touched by Islam prior to the eleventh century. However, camel-breeding no...