![]()

1 From Empire to Colony

The Great Depression and Nigeria

AT THE ONSET of the Depression, British economic recovery policy in Nigeria focused on the strict implementation of austerity measures approved by the Colonial Office in London, whose prescriptions, in turn, were inspired by the economic recovery consensus in Britain. But as my analysis will demonstrate, the economic recovery plan of the Nigerian colonial state existed merely to maintain a semblance of economic and sociopolitical stability. Already in financial crisis, with dwindling trade surpluses and profits, the state found its ambition to remove surpluses and resources from Nigeria in peril. Colonial exploitation was thus a foreclosed proposition, and the state became preoccupied with less ambitious but equally disruptive alternatives.

By enforcing the policy of imperial preference vigorously, the state curtailed Nigerians’ buying choices and made sure that their purchases benefited Britain. It cut the pay of African colonial auxiliaries and collected income taxes with a new enthusiasm. It retrenched many Nigerian colonial auxiliaries, worsening an already bad unemployment problem. To boost revenue and the state’s capacity to lubricate its administrative machinery, colonial officials intervened robustly in the domain of export agriculture.

These actions resulted from the colonial state’s own financial anxieties, and officials saw Nigerians’ economic interests and suffering as merely incidental to the state’s. This was not exploitation at work, but a desperate, cynical colonialism committed, temporarily, to self-preservation for its own sake. These economic recovery measures intensified Nigerians’ suffering and economic insecurities, to be sure, but their victimhood remained incidental to state recovery efforts. More important, the unsavory effects of these efforts masked the state’s own economic insecurities, which threatened to expose and undermine British colonialism’s paternalistic machismo. The pursuit of economic recovery carried the theoretical possibility of propping up state finances, thus helping officials maintain an illusion of administrative stability and political control. But it also carried the risk of exposing the state to Nigerians’ anger, frustration, and distrust. Furthermore, it intensified a fundamental, preexisting weakness of the state: precarious political control.

Colonial Nigeria

BRITAIN, DEPRESSION, AND EMPIRE

The Great Depression was marked in Great Britain by acute unemployment, an unusual decline in exports, and a drastic reduction in the volume of new investments. By September 1931 the problem of the overvaluation of the pound in world markets had become obvious, taking a toll on British industries. Britain departed from the gold standard in the same month, reverting to a free-floating exchange rate, which, while good for export-oriented industry, opened the way for a currency crisis, panic, and an aggressive quest for precious metal that would engulf Britain and the empire.

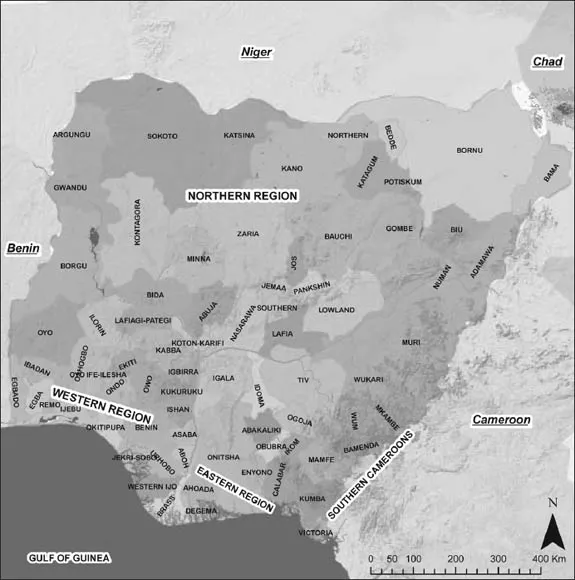

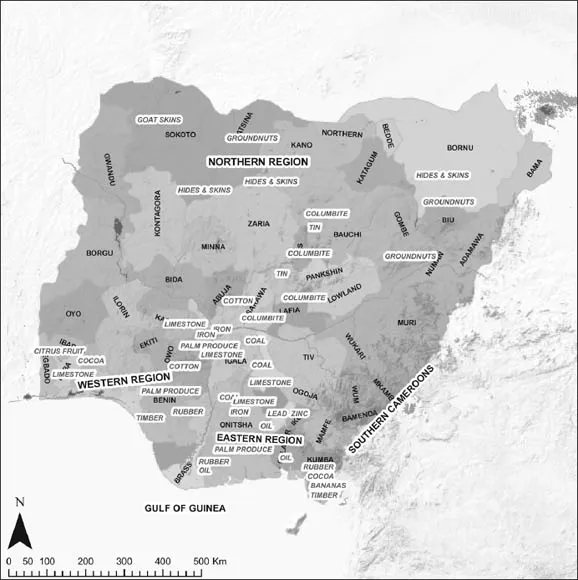

Nigerian agricultural exports and mineral deposits

A long history of recessions helped shape Great Britain’s experience of, and reaction to, economic downturns, leaving it remarkably sensitive to sudden economic changes. The Depression inaugurated a new period of economic nationalism in Britain. That nationalism was, however contradictorily, bound up with a novel economic solidarity that operated along the lines of empire. In 1929 local desperation for recovery led to institutionalized mechanisms for survival and inspired a heightened consciousness about the economic importance of empire and of shared imperial economic fates. The economic recovery measures that emerged in Britain maintained this new idea of empire, emphasizing empire as a safety cushion during hard times, a domain to be isolated from global economic competition in the interest of Britain.

From the late 1870s Britain went in and out of recession, and the cycle of boom and bust began to register on the national consciousness.1 The depression of 1921 to 1923 firmly entrenched what some would call a depression mentality in state officials and gave authority to policies bordering on economic protectionism and solidarity of the empire. During the early 1930s this British preoccupation with economic crisis led a minority of mostly non-British commentators to wonder, somewhat cynically, if Britain was not “generically in a Depression” or at least getting what it had always planned for.2 Most Britons adjudged the preemptive and reactive economic policies justifiable by the seemingly unique economic vulnerability of their country. Within Britain any efforts calculated to bring succor to British citizens during the Depression met with an overall favorable reception. The consensus in Britain favored both familiar and novel ways of managing economic crisis. In this atmosphere of heightened economic desperation, imperial solidarity and colonial outposts became fulcrums of economic recovery.

IMPERIAL SOLIDARITY TO THE RESCUE

British economic recovery measures focused largely on imperial solidarity. A shift toward protectionism and economic territorialism enabled and sustained the decisive shift toward an empire-based economic recovery. Globally, economic territorialism had become an acceptable, if problematic, way of responding to the Depression. In the words of Arthur Schlesinger, “Every country tried to seal itself, tried to contain the economic consequences of Depression, tried to prevent other countries from exporting their own troubles.”3 As Britain struggled to incorporate the empire into its domestic efforts to mitigate the economic damage of the prevailing hardship, the emerging trend toward economic isolationism compelled it to further rally the empire around a common principle of economic solidarity. Germany, France, Austria, Italy, Japan, and other Western economies crafted nationalistic responses to the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930, which closed American markets to foreign goods. The ensuing tariff war merely aggravated the Depression. Britain’s acutely protectionist response reflected the contours of empire. Its empire-based economic recovery measures included retaliation against the Americans and a desire to inoculate itself against the perceived disruptive effects of free trade. Britain’s rather unique position as the guardian of a large empire, which had long functioned, however loosely, as an economic unit, shaped this new policy of protectionism.

Few British voices condemned protectionism altogether, and fewer still berated the creation of a protected empire market as a bulwark against the vicissitudes of global markets.4 For the most part, the British public remained agreeable to all measures deemed necessary to protect them from the Depression, including those that promoted economic recovery through the sacrifices of people in the British Empire. Protectionism gradually became a tolerated item on the economic emergency menu—not as an accepted economic virtue but as a cushion against the unsavory outcomes of global market turbulence. From this consensus of imperial economic solidarity emerged lobbies and pressure groups to champion the concept of imperial sacrifice in Britain.5 After the second imperial economic conference in Ottawa, Canada, in 1932, Britain and the empire formally entered into a period of economic cooperation that would last through the Depression. The groups that lobbied for the conference remained active and constantly defended the principles behind the Ottawa tariff agreements. These agreements all but closed the empire to nonempire goods, while promoting exports and imports, even at uncompetitive prices, between empire countries. Some groups even called for “a common monetary policy throughout the empire.”6 The doctrine of “recovery through empire,”7 which was popular in the economically desperate period after World War I, enjoyed a renaissance during the Depression as a slogan that encapsulated Britain’s focus on economic recovery.

The Ottawa agreements, which formalized British commitment to imperial preference as a tool of economic recovery, understandably led to a trade war between the United States and Britain. The former needed the raw materials of the British Empire; but under the terms of Ottawa it would have to contend with prohibitive tariffs. Short of smuggling, the United States could no longer import mineral raw materials directly from British Empire countries. This had serious implications for Nigeria and Britain, especially because the U.S. War Department had classified tin as a strategic commodity after World War I. Ninety-five percent of the world’s tin was produced in the British Empire—Northern Nigeria, Malaya, and the British East Indies. British tin-mining companies had benefited enormously from U.S. patronage before Ottawa. The terms of the Ottawa agreements changed that transaction to the disadvantage of the United States.

Imperial-preference tariffs and the effort of Britain to boost dwindling tin prices through production cuts seriously affected a tin-producing colony like Nigeria. In an era of falling prices, price gains from production cuts did not keep pace with the economic repercussions of closing mines that had become a source of livelihood and a market for thousands of Nigerian farmers. Tin was not only a major export from Northern Nigeria, it also gave rise to and sustained a vibrant trade in foodstuffs and a culture of migrant-labor remittances that sustained the economy of a large area. The manipulation of tin output and the subsequent reduction in tin mining destabilized the equilibrium of local patterns of exchange and economic sustenance in the tin-mining areas of Nigeria. The use of tariffs to block the entry of competitively priced goods from outside the empire economically punished the consumers of Nigeria.

Imperial preference ensured that Britain cornered most of Nigeria’s market for manufactured goods, while shutting out rivals. During the Depression the bulk of Nigeria’s major import—textiles—came from Britain. In 1932, 85 percent of Nigeria’s imported textiles originated from Britain; the rest came from Japan, Italy, Germany, Holland, France, and India.8 The preferential tariffs and the quota system put in place by Ottawa protected the flow of British imports, which were priced above products from rival countries, especially Japan. British officials moved more vigorously against Japanese textiles because Japanese products were the least expensive and therefore more attractive to smugglers.9 Imperial preference also secured the Nigerian market for tobacco and salt. While the policy limited the range of choices open to Nigerian consumers, it helped keep British merchants in business.

British merchants and British industries took advantage of the Depression to increase their gains from Nigeria in other ways. The colonial authorities imposed new export duties on palm kernels, cocoa, groundnuts, and other Nigerian exports in late 1929. While designed to increase the government’s revenue base at a time of contracting revenue, the new duties inadvertently supplied British merchants, long schooled in the art of manipulating local producer prices, a platform to exact more monetary concessions from Nigerian agricultural producers. Although some European mercantile firms initially protested the new duties imposed by the government, it soon emerged that their protests were most likely designed to make up for a practice crafted by the mercantile firms that was equally detrimental to the interests of Nigerian producers. In response to dwindling earnings during the Depression, British shipowning merchants formed combines all over West Africa, through which they set uniform produce-buying prices and freight charges. They set the former conveniently low and the latter high.10 This arrangement between the shippers and the produce-buying merchants reduced the average income of the local producers of groundnuts, cocoa, palm kernels, and cotton.

The new system transferred new charges to local producers, reducing their earnings and engendering discontent. At the United Africa Company (UAC), which specialized solely in buying produce from the Nigerian hinterland (and was therefore closer to producers), officials quickly observed the level of resentment and began as early as 1930 to advocate dismantling the shipping combines. The UAC disliked the virtual freight monopoly that Elder Dempster, the major shipping line in British West Africa, and other companies of the conference shipping lines, had over West African trade, charging that the shipping monopoly was “exacting exorbitant and unconscionable charges from producers, merchants, and traders.” The UAC argued that this amounted to “penalizing producers and purchasers of African products by causing low prices to be paid for produce and high prices to be paid for European goods in [West] Africa.”11

The UAC’s position was not entirely altruistic, though; the company hoped to exploit competition among the various shipping companies to its advantage. As the biggest produce buyer in West Africa, it would reap considerable benefits from a competitive shipping regime. However, the vehemence with which it pursued the campaign—threatening to stop all dealings with the shipping combine—mirrored the pressure it may have incurred from local producers and merchants, who ultimately bore the brunt of the freight charges. Few if any alternatives to the combine existed. Patronizing small independent shipping companies tended to be more expensive and riskier than patronizing the combines. Caught between two unfavorable options, British produce buyers simply passed on the excessive charges to local producers. Moreover, as one contemporary Nigerian commentator argued, competition during the Depression hardly resulted in cheaper shipping charges or higher buying prices.12

Such was the plight of the Nigerian producer during the 1930s. Interestingly, while accusing the newly formed Elder Dempster shipping monopoly of excessive charges, the UAC ignored its own previous shipping monopoly (while trading as the Great Niger Company) along the banks of the Niger, which now came under question.13 A group of Nigerian merchants published an article (a rejoinder to the UAC’s well-publicized indictment of Elder Dempster’s alleged exploitative practices) that accused the UAC of hypocrisy. The merchants admitted that, “by these excessive freights, producers have been badly paid for their produce” and that “there had been abuse of ship owners’ monopoly,” but they questioned the motive of the UAC—itself no stranger to the practice of transferring its financial distress to local producers and merchants.14

A contemporary Nigerian newspaper columnist succinctly captured the importance of the shipper-merchants’ conspiracy. He remarked cynically about the British merchants, “These intellectual giants overlooked the fact that the West African consumer would be unable to purchase Lancashire goods unless he obtained a reasonable price for his products.” He urged the colonial government to fulfill the wishes of “the people of Nigeria who have suffered from an unexampled Depression” and are looking forward “almost despairingly” to the government to “destroy monopoly and open the markets of West Africa to equitable competition.”15 This columnist touched on the poignant dilemma inherent in the self-cushioning practices of British shipper-merchants and the acquiescence of colonial authorities. He distilled the problem into one crucial point: that an excessive disregard for the economic stability of local producers could hurt Br...