![]()

ONE

THE MORAL TREATMENT EXPERIMENT

“A Magnificent Site Overlooking the Hocking Valley”

On a spring day in 1865, Dr. William Parker Johnson returned home to Athens, Ohio, from the Civil War. He had been mustered out from Camp Dennison in Columbus, Ohio. Three weeks earlier, General Robert E. Lee had surrendered the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia to Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant. Dr. Johnson, known to friends and family as Park, was a country doctor. He had enlisted in the Eighteenth Ohio Volunteer Infantry as a physician and finished his war career as head of two post hospitals in Tennessee, where he found a calling as an organizer and administrator. He returned to Athens transformed from country doctor to experienced hospital administrator by his work caring for the ill and wounded of the Kentucky and Tennessee battlefields.

Politics

Men who survived the Civil War returned home to resume their lives; some were shattered in body or mind and others had gained new leadership skills and recognition for heroic achievements. The political careers of Ohio-born presidents Ulysses S. Grant, Rutherford B. Hayes, James Garfield, Benjamin Harrison, and William McKinley were launched by their service as Civil War officers.1 Dr. Johnson used his war experience and newly developed administrative skills to advance the care of those with mental illness in Ohio by orchestrating the founding of Ohio’s fifth state mental hospital, the Athens Lunatic Asylum.

Post–Civil War Ohio was of national significance in the nineteenth-century public mental health care movement sweeping the nation. The Ohio Lunatic Asylum, opened in the state’s capital of Columbus in 1838, was the first public asylum west of the Allegheny Mountains.2 Between 1838 and 1898, Ohio opened seven public asylums to provide mental health care for the state’s large and rapidly urbanizing population. All seven were devoted to care based on the newest humanitarian models of mental health care. Some of Ohio’s asylum physicians during this period attained national stature, publishing and providing leadership in the newly forming field of American psychiatry. And Ohio in the last quarter of the nineteenth century was an American political and economic powerhouse. Ohio sent five presidents to the White House between 1877 and 1901. Entrepreneurs such as Dr. B. F. Goodrich, Edward Libbey, and John D. Rockefeller established small businesses in Ohio that grew into giant industries. Ohio’s natural resources fueled the nation’s steel, natural gas, oil, and clay pipe industries, while the state’s railways and water transport on Lake Erie and the Ohio River provided a dense network of transportation between the East and the rapidly expanding markets of the West.3

In contrast to the urban centers of Cincinnati, Columbus, Toledo, Dayton, and Cleveland, Athens remains even today a small village in a remote rural corner of Ohio. Established in 1804 by the General Assembly of Ohio as the home for Ohio University, Athens was surveyed in 1795 by the Ohio Company, whose associates were among those who settled the midwestern wilderness under the Ordinance of the Northwest Territory, 1787.4 The village’s 1870 population of seventeen hundred persons and its isolated location in the steep, forested foothills at the edge of the Appalachian Mountains made it an extraordinary choice for the location of Ohio’s fifth state asylum.

Dr. Johnson’s first year as a war doctor was difficult. He was often depressed and in despair about alleviating the human misery created by war, as he wrote to his wife, Julia, in Athens from Camp Jefferson at Bacon Creek, Kentucky, in June 1861:

My shoulders are pretty broad and I guess I can go on awhile although I hope our regiment will not continue long in its distressed condition. I thought yesterday we were about through with measles but found seven new cases today. The chances for making the sick men comfortable are miserable and I dread the consequences very much—we have lost but one case yet. We have on hand now a number very sick and several will have to die I fear. People have little idea of the horrors of war—it is not easy to be on a battlefield however I do not think it best to distress your tender feelings with any particulars and I presume it is not best for you to mention anything about the facts I have stated as so many of the Athens people have friends here. . . . [W]hen will this accursed war be at an end?5

FIGURE 1.1 Dr. William Parker (“Parks”) Johnson, brigade surgeon in the Eighteenth Ohio Infantry. He was elected to the Ohio legislature in 1864 while serving in the Union Army. Courtesy of the Mahn Center for Archives and Special Collections, Ohio University Libraries.

FIGURE 1.2 Julia Blackstone Johnson, wife of Dr. William Parker Johnson. Courtesy of the Mahn Center for Archives and Special Collections, Ohio University Libraries.

But Dr. Johnson persisted and later wrote Julia of his success in organizing his work. His letters suggest that his interest in mental health care may have been a result of his observations of soldiers in distress for no apparent physical reason and his puzzlement as to how to treat them in his hospitals.

It is a matter of astonishment how much one man can do when he goes at it with a will. I would not have believed a month since that it were possible for one (me) to do what I have done for the past two or three months. . . . It will have at least one good effect in learning me to be ready to do the right thing at the right time. I have my labors so systematized that I have a time for each only and aim to discharge it just at the proper time. I have got the men learned so that there is a time set apart for each particular entry. For instance all who are on the complaining order in camp must make their complaints known between the hours of light and ten in the morning. . . . One of my great perplexities is what to do with men who claim to be sick and yet present no outward symptoms of disease.6

Despite a massive workload, diarrhea, and occasional bouts of depression, Dr. Johnson came to appreciate his work. From Tullahoma, Tennessee, he wrote that while he worried constantly about his family and missed the comforts of home, he preferred the regularity of life as an army physician to working in the hills of Appalachian Ohio as a country doctor:

Doctor Mills got sad news from home last night. One of his children died and his wife and his three other children were all very sick with scarlet fever. Poor fellow he is almost distracted. He applied today for leave of absence but could not obtain it. I have urged him to go anyhow. . . . It is the one real drawback to being a soldier the constant anxiety about the loved ones at home. So far as the mere labor is concerned, I would rather occupy my present position than return to my old practice over the Athens County hills. I can be more regular in my meals (if they are sometimes very poor) and lose less sleep than in my old practice at home but nothing can compensate for the loss of the endearments at home and its precious treasures.7

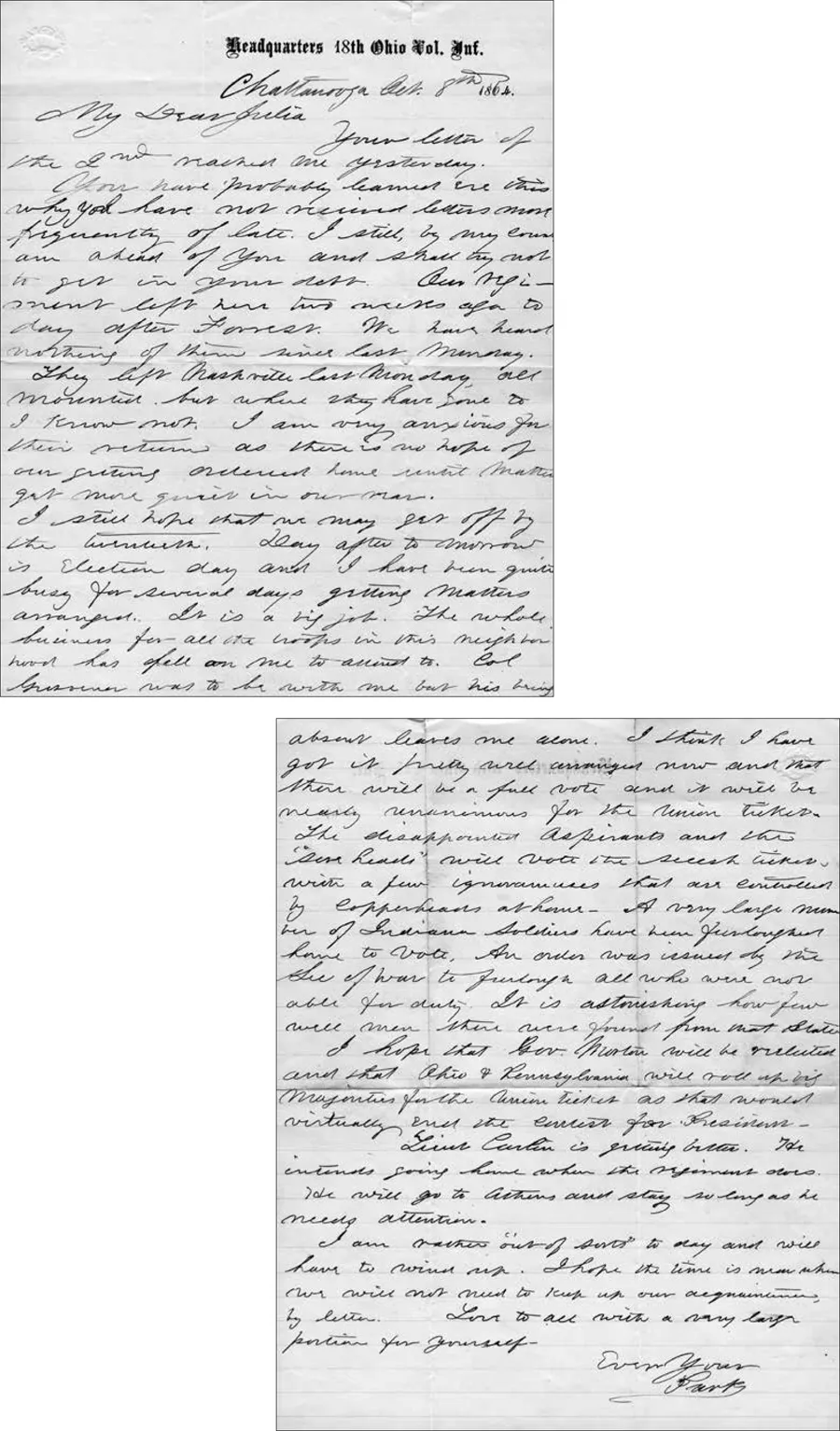

FIGURE 1.3 Letter to his wife, Julia, from Dr. William Parker Johnson, Athens physician and head of two Union post hospitals in Tennessee. An Ohio legislator, Dr. Johnson orchestrated the founding of the new asylum in 1867 and its location in Athens. While away at war, he wrote often to Julia. In this letter, he discusses the 1864 presidential election. Courtesy of the Mahn Center for Archives and Special Collections, Ohio University Libraries.

Late in 1863, Johnson was given greater administrative responsibility. Writing to Julia from Murfreesboro, Tennessee, he described his new work and reflected again on the horrors of war:

I mentioned in my letter to your father that I had been put in charge of a Post Hospital here. I have got it fitted up very comfortably and all men (except some who were slightly wounded sent to Nashville) in it. Today I received orders to take another Hospital under my charge. I protested against both for the reason that I already had enough to do and also for the reason that it was in such a miserable condition. I was informed that that was the reason that it was put in my charge so that its condition might be improved. . . . War has its Glories but it has also its thousand horrors and human tortures that would sicken any feeling heart. I have often wished to see a big battle but I pray to God that I may never witness again such scenes as I have had to for the last two weeks. I have no desire to horrify you with any attempt at a description and could not give the subject justice should I attempt it.8

Just before he returned to Athens from the war, Dr. Johnson was elected to the Ohio legislature, where in 1867 he orchestrated the founding of the Athens Lunatic Asylum. Having learned well his organizational lessons from his war work, Johnson did “the right things at the right time” to secure state approval for a new asylum and ensure its location at Athens. First he helped a legislator from a nearby county craft a resolution in the General Assembly directing Ohio’s Committee on Benevolent Institutions to look into the needs of those with mental illness in Ohio. The resolution passed in 1866. Second, as chair of the Committee on Benevolent Institutions, Johnson solicited from the state medical society, of which he was a member, reports to the legislature supporting the need for more institutions to serve those judged insane. Finally, Johnson prepared a bill authorizing the construction of the fifth state asylum. This bill, entitled “An act to provide for the erection of an additional lunatic asylum,” passed in 1866 and became a law in 1867. Finally, in a deft political move, Johnson saw to it that Athens businessman E. H. Moore was appointed by the governor as one of three trustees of the new asylum charged with choosing its location. Moore organized the Athens community to collect money for the purchase of the site and offer it free to the state. After considering more than thirty locations, it came as no surprise to anyone that the trustees settled upon Athens.

The village of Athens celebrated the laying of the cornerstone of its asylum with a parade of nearly ten thousand persons. The new institution coming to town was of great economic and political importance to its residents, who staged an enormous celebration. On Thursday, November 5, 1868, at two o’clock in the afternoon, one thousand Masons from all over Ohio, a brass band, two church choirs, judges, the mayor of Athens, the village council, hundreds of townspeople, and thousands of supporters from other areas marched down a long hill across the old South Bridge spanning the Hockhocking River9 and up the great hill to the asylum grounds.10 Ohio’s fifth state-supported asylum to treat persons with mental illness was to be a Kirkbride hospital, the gold standard for Victorian-era mental hospitals. Kirkbride hospitals were built to the most rigorous specifications of moral treatment, the prevailing psychiatric treatment of the time.

The Kirkbride Plan

Dr. Thomas Kirkbride’s interpretation of moral treatment, developed at the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, was the crown jewel of nineteenth-century American psychiatry.11 He proposed that mental illness was curable, that physical punishment and restraints should be abolished, that treatment of those with mental illness as though they were capable of rational behavior was curative, and that a system of routines and diversions in a restful and supportive setting was therapeutic. Dr. Philippe Pinel, physician for two asylums in Paris, touched off the moral treatment movement in 1795 when he allegedly removed chains from his patients and undertook humane, compassionate, and supportive care. He dubbed his method traitement morale, meaning ethical, honorable treatment. This approach was a radical alternative to well-established aggressive, punitive tactics of curing mental illness with punishment and restraints. A year later, in 1796, William Tuke, a Quaker tea merchant, opened the York Retreat for persons with mental illness, using kindness, reason, and a family atmosphere rather than the medical treatments of the time.12

Nineteenth-century asylum physicians dedicated to moral treatment believed that mental illness was curable through proper habits and a regular, healthy life. Dr. William H. Holden, superintendent of the Athens Lunatic Asylum, described moral treatment in his 1879 annual report to the Board of Trustees:

Under the head of moral treatment must be considered all those means that tend to lead the mind into a normal and healthy channel, and direct the thoughts, as much as possible, in another course, remote from their delusions. See your patients frequently; talk to them, give them kind words and pleasant looks; encourage them as much as possible. Give them moderate exercise. Walking, riding, and driving in the open air have a tendency to break the monotony of asylum life and add to the comfort ...