![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Help Wanting

The Exhaustion of a Dickensian Ideal

“When you have sat at your needle in my room, you have been in fear of me, but you have supposed me to have been doing you a kindness; you are better informed now, and know me to have done you an injury.”

—Dickens, Little Dorrit

In July 1860, Dickens published a piece in All the Year Round containing a devastating scene of philanthropy gone wrong. The article relates Dickens’s own experiences as, during a night of insomnia, he rambles “houseless” through central London and Southwark. A bell tolling three o’clock finds him on the steps of St. Martin’s:1

Suddenly, a thing that in a moment more I should have trodden upon without seeing, rose up at my feet with a cry of loneliness and houselessness, struck out of it by the bell, the like of which I never heard. We then stood face to face looking at one another, frightened by one another. The creature was like a beetle-browed hair-lipped youth of twenty, and it had a loose bundle of rags on, which it held together with one of its hands. It shivered from head to foot, and its teeth chattered, and as it stared at me—persecutor, devil, ghost, whatever it thought me—it made with its whining mouth as if it were snapping at me, like a worried dog. Intending to give this ugly object money, I put out my hand to stay it—for it recoiled as it whined and snapped—and laid my hand upon its shoulder. Instantly, it twisted out of its garment, like the young man in the New Testament, and left me standing alone with its rags in my hands.2

What is gained, what even is learned, in this encounter? Imagine the cold March night in Trafalgar Square, a young man in rags, harried by the elements and by his imagination, faced suddenly by—not a Brownlow or a Cheeryble but the father of all the Brownlows and Cheerybles, the very conscience of philanthropy. For decades Dickens had urged readers to reach out to lost souls like this beetle-browed youth.Yet now his own helping gesture comes to nothing. It does not matter that Charles Dickens passed by; an alderman or policeman, or an actual devil or ghost, would have done just as well. The futility of the scene seems to forfeit the social mission of the earlier Dickens, for there can be little hope for charity when the poor recoil from help as they would from harm.The benefactor too is called into question as a possible “persecutor,” his companionship becoming theft as he inadvertently seizes the youth’s only garment.3 Philanthropy is no longer a solution to the failures of society; it has proven itself a failure as well. And yet, while this scene is a testament to that failure, it contains traces of the hope that has been abandoned: the ideal of personal charity.

I use the phrase “personal charity” to denote a particular strain in Victorian discussions of philanthropy. Borrowing the logic of condescension, proponents of personal charity held that the primary (or exclusive) function of philanthropy should be to multiply the points of contact between rich and poor, a contact that had been increasingly attenuated by the stratifications of modern urban life. Rather than contribute to the economic relief that was the sole province of the state, philanthropists should personally visit hospitals, prisons, schools, workhouses, and, of course, the homes of the poor. Through individual scenes of personal contact, each class would exert a salutary influence on the other. The rich would advise the poor on matters spiritual (scripture, doctrine, prayer) and temporal (economic and domestic management, health, hygiene), while the poor would remind the rich of the necessity of Christian charity and would often provide examples of fortitude, dignity, and (paradoxically) independence.

Dickens embraced the personal approach to philanthropy, particularly in what I call his middle period, from Dombey and Son (1846–48) to Bleak House (1852–53).4 During these years, Dickens moved away from the vision of general benevolence he had supported in his earlier novels and looked for solutions that would draw rich and poor into a much tighter scheme of relation. Yet Dickens’s brand of personal charity reached beyond the regular philanthropic ideas of familiarity and influence to incorporate the idea of restitution—action that proceeds from a recognition of another’s claims. In Dickens’s middle novels, charity leads directly to restitution through the exposure of shared personal histories between rich and poor, histories that hinge on a primal moment of injury or failed paternity. Far from merely activating the powers of influence, charity effects an actual or symbolic resumption of paternity or reversal of some prior wrong.

Dickens’s narratives of restitution temporarily find their expression in the operations of personal charity, but in the later novels, restitution presents a serious challenge to the entire philanthropic enterprise. This new attitude reflects the incipient socialism that, in the decades after Dickens’s death, would convince the nation at large that philanthropy was an insufficient means of maintaining the social welfare. The proponents of state regulation (in matters such as housing and wages) argued that relief to the poor must be seen not as a philanthropic measure at all but as an assertion of economic justice. Charity was a palliative for the consciences of the rich, who could thereby demonstrate their solicitude for the poor without compromising the foundations of their own economic dominance. As an example of the new socialist thinking, I cite Arnold Toynbee’s famous 1883 confession (excerpted from Beatrice Webb’s autobiography):

We—the middle classes, I mean, not merely the very rich—we have neglected you; instead of justice we have offered you charity, and instead of sympathy we have offered you hard and unreal advice; but I think we are changing. If you would only believe it and trust us, I think that many of us would spend our lives in your service. You have—I say it clearly and advisedly—you have to forgive us, for we have wronged you; we have sinned against you grievously—not knowingly always, but still we have sinned, and let us confess it; but if you will forgive us—nay, whether you will forgive us or not—we will serve you, we will devote our lives to your service, and we cannot do more.5

Toynbee’s account names charity the enemy of restitution, a designation that was forecast by Dickens’s own late-career change of heart. In Little Dorrit (1855–57) and afterwards, Dickens attacked the very form of personal charity that had previously proven so vital, showing it to perpetuate precisely the kinds of failures that it had earlier served to expose and expiate.The following pages consider the uses to which Dickens put the idea of personal charity during his middle period, and the reasons he later abandoned it.

Haunted Philanthropy

When Dombey’s Alice Marwood, a fallen woman, angrily rejects the alms offered her by Harriet Carker, she performs an act that will be frequently rehearsed throughout Dickens’s later novels. Jack Maldon, Jo, Richard Carstone, Amy Dorrit, Miss Wade, Lizzie Hexam, Betty Higden, and even Silas Wegg find occasion to refuse or resist offers of charity.Yet Alice’s refusal of help, conventional as it would later become, is far from automatic; it takes her several hours to return the money, hours that carry her into and back out of London and involve her in emotions ranging from intense gratitude to agonized rage. The whole transaction can be charted as follows:

1. Alice is “contemptuous and incredulous” toward Harriet’s kindness;

2. Alice relents, becomes grateful;

3. Harriet gives Alice money, which Alice accepts as a token of her benefactor;

4. Alice delivers the money over to her mother;

5. Alice learns that Harriet is the sister of her enemy;

6. Alice seizes the money from her mother;

7. Alice returns to Harriet and replaces her gratitude with a curse;

8. Alice throws the money to the ground.

By opening a significant gap between Harriet’s offer and Alice’s refusal, Dickens suggests that the rejection of charity is not the spontaneous expression of a particular attitude but the culmination of multiple motives, attitudes, and effects. Even a first reading of the list above prompts various speculations about the psychological process of such a rejection: that the recipient’s anger is predicated on an initial relenting; that the recipient must accept the money before she can reject it (cast it back); that it is not general suspiciousness but a particular suspicion (or allegation) against the donor that causes the recipient to turn on her; and that in the encounter between a donor and a recipient, other voices and interests (represented here by the mother) may be brought to bear. All of these issues complicate our picture of charity and its failures.

One conspicuous aspect of the transaction is that, whether Alice accepts or returns the alms, the money cannot stay in her hands. At the instant Alice arrives in the city, her mother asks her for money: “The covetous, sharp, eager face with which she asked the question and looked on, as her daughter took out of her bosom the little gift she had so lately received, told almost as much of the history of this parent and child as the child herself had told in words” (491). The demands of an avaricious mother are surely meant to signify the inescapable cycle of criminal poverty—the idea that when one is forced continually to revisit her degraded origins, she has little chance to reform. But the profits of charity are ephemeral in a more mundane sense as well, as they are quickly lost to the hard contingencies of urban survival.6 A little money can do nothing to improve Alice’s connections, erase her crime, find regular work for her. Rejecting the donation therefore becomes a way for her to repossess it. As she seizes the money from her mother, Alice ensures that it will nourish a private and sacred cause—the cause of her anger and vengefulness—instead of feeding the parasitic demands of her ordinary life.

It is not just the money that Alice repossesses at that moment; she instantly returns in her mind to the very moment of the donation, so that she can construct a new image of what actually happened:

“Stop!” and the daughter flung herself upon her, with her former passion raging like a fire. “The sister is a fair-faced Devil, with brown hair?”

The old woman, amazed and terrified, nodded her head.

“I see the shadow of him in her face! It’s a red house standing by itself. Before the door there is a small green porch.” (493)

The scene unfolds anew before Alice’s eyes, but differently; Harriet is now a “fair-faced Devil.” Such an epithet may well have suggested itself to Alice in her initial “contemptuous and incredulous” apprehension of Harriet. If so, it has remained with her, ready to resurface if her interpretation of the scene should require it. The rejection of charity, then, involves not only a repossession of the alms but also a reconstruction of the past. Once arrived at Harriet’s house, Alice further exercises the drive to reconstruct: “If I dropped a tear upon your hand, may it wither it up! If I spoke a gentle word in your hearing, may it deafen you! If I touched you with my lips, may the touch be poison to you! A curse upon this roof that gave me shelter!” (495). The battle for the present—who will have the money?—is revealed to be a battle over the past. To refuse charity, Alice must look backward.

For Dickens, acts of charity are fundamentally concerned with this backward-looking reconstruction of the past. Harriet cannot look at Alice’s “reckless and regardless beauty” without imagining the state she has fallen from, and Alice, in describing her own abjection to her mother, links together scenes of her past history as a child, then a girl, then a criminal, now a woman. In the same novel, Polly Toodles fears that Biler’s tenure at a charity school will sever him from his family, and she wants to reach him before he loses hold of his past: “She spoke, too, in the nursery, of his ‘blessed legs,’ and was again troubled by his spectre in uniform. ‘I don’t know what I wouldn’t give,’ said Polly, ‘to see the poor little dear before he gets used to ’em’” (60). Both the desire to help out and the willingness to be helped are connected with memories of the past. Thus, John Carker takes an interest in Walter, who reminds him of the hopeful days of his own youth; Edith Dombey looks after Florence, a daughter who may still, unlike herself, be rescued from parental neglect; the prostitute Martha (David Copperfield) helps rescue Emily after she too falls; and Redlaw (The Haunted Man) finds, through Edmund Longford, a way to forgive the injuries of his own past. A study that wishes to integrate Dickens’s scenes of charity with the most profound aspects of his narrative and social imagination must begin by asking what charity has to do, specifically, with reconstruction and revision.

Critics have noted that Dickens’s class aspirations, and the hopes and fears generally held by a precariously mobile lower middle class, make the question of origins a vexed one.7 For those struggling upward, the past supplies alternating images of shame and security, images available to be sorted, selected, forgotten, and recovered. Complementing these impulses is the novelist’s conventional turn to the personal past as a setting for the most outrageous fantasies of suppressed identity and improbable affiliation—not merely in the sensation novels that surrounded Dickens in his final decade but in the great novels of his youth, in Jane Fairfax’s secret love affair and Roland Graeme’s hidden ancestry. But it is Dickens’s brazen innovation to use such a past—the personal as opposed to the cultural past—as a framework for the utopian reconstruction of social relations in the present. Dickens removes the act of charity from the utilitarian realm of policy and measured outcomes and reveals it to be the reenactment of some primal and specific scene of alienation. The benefactor and the needy are invariably linked by a set of concrete circumstances that take three characteristic forms: (1) the object of solicitude sparks a remembrance in the benefactor of his or her own early life, as with Martha and Emily; (2) the benefactor turns out to share a suppressed kinship with the needy, as with Alice’s eventual intercession on behalf of Edith Dombey; and (3) the benefactor has had some actual role in causing the suffering of one she intercedes for, as with Mrs. Clennam and Amy Dorrit. Personal charity in Dickens advances far beyond the standard philanthropic program of forging a better acquaintance between rich and poor. It thrusts both classes upon an imaginary landscape in which they are always already related, whether through identification, kinship, or criminal culpability.

The Haunted Man (1848) bears out Dickens’s conviction that the success of charity depends on the reconstruction or recovery of a shared past. At the story’s opening, Redlaw (a chemist) is a haunted man, suffering from the memory of a past injury. Redlaw is granted his wish to forget the sorrow of his past life and remember only the good, but he gradually finds that in the process of forgetting injury, he has lost his ability to feel compassionate toward others’ sorrows.8 Meanwhile, the chemist passes on his forgetfulness to all who come near him, always with the same effect: as soon as the sorrows of the past vanish, so does the compassion of the moment. This reprieve from sorrow proves fatal to the capacities both to help and to be helped. A mother loses interest in her infant children; a father has no pity for his dying son; a patient cannot tolerate his nurse; a prostitute slips beyond the pale of recovery. The hauntedness (shame, guilt, indignation, regret, loss) that had seemed a problem turns out to be a desirable condition, the only possible means to a constructive benevolence. While trying to escape his sorrowful past, Redlaw comes to realize that he has endangered his moral integrity—“integrity” in a chemist’s sense of the word—and has cut himself loose from the community of suffering humanity. The story thus vindicates hauntedness and denounces any cure that would sever the ethics of the present from the trauma of the personal past.

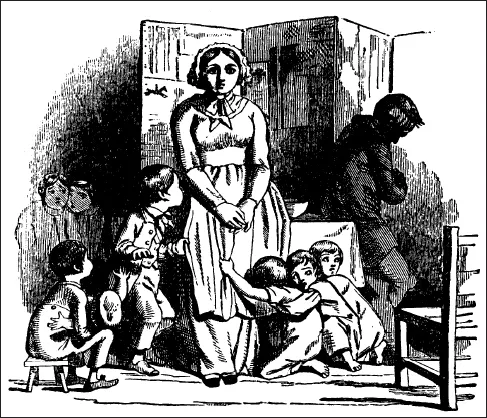

The practical consequences of such a break are serious indeed, and the story traces these consequences, in allegorical fashion, across the diverse landscape of human life. For instance, Redlaw meets a fallen woman who is haunted by sorrowful memories of better days but loses all of her qualms of conscience once she begins to forget her past. “‘Sorrow, wrong, and trouble!’ he muttered, turning his fearful gaze away. ‘All that connects her with the state from which she has fallen, has those roots!’” (367). The chemist is “afraid to think of having sundered the last thread by which she held upon the mercy of Heaven” (367). Similarly, when Redlaw encounters a criminal who, softened by the pleadings of his father, is at the point of renouncing his career, Redlaw’s presence restores to the man the boldness to eschew repentance and salvation. In another scene that is less sensational but even more pointed than these, Mrs. Tetterby, a mother of eight, ceases to care for her children and grows contemptuous of her husband. As she is later to describe it, “I couldn’t call up anything that seemed to bind us to each other, or to reconcile me to my fortune. All the pleasures and enjoyments we had ever had—they seemed so poor and insignificant, I hated them” (349). Mrs. Tetterby’s indifference to her family is wrenchingly portrayed in Tenniel’s illustration, which shows her surrounded by her clinging children, who try to get her attention as she sits motionless and stares vacantly out of the frame.

FIGURE 1. Mrs. Tetterby, from John Tenniel’s “Illustrated Double-page to Chap.II,” in The Haunted Man and the Ghost’s Bargain. Charles Dickens, Christmas Books (London: Chapman and Hall, 1913). Mervyn H. Sterne Library, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The mother has drifted away from her family and can only recognize afterwards that it was her sorrow, sweetened by memory, that had anchored her to her home. Severing the link to sorrow, then, does not simply impair a person’s benevolence; it reconfigures her whole ontology, such that she becomes a creature of the moment. As in Dickens’s other Christmas narratives (such as the earlier A Christmas Carol and the later “What Christmas Is as We Grow Older”), the authentic life is shown to be the one that holds past, present, and future together ...