![]()

Chapter 2

TWO VILLAGES IN YOGYAKARTA

Daerah Istimewa (D. I.) Yogyakarta, the special region of Yogyakarta, is located in south-central Java. It is “special” both by history and by political designation. From ancient times to the present, Yogya, as it is more familiarly known, has been recognized as the center of Javanese culture and society, the product of a long syncretic accumulation of religious and cultural movements that include animism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, and indigenous Javanese elements. Although Islam has been fully entrenched for three centuries as the dominant religion and social influence, the area remains heavily permeated with the remnants of its predecessors. Islamic values and practices often merge with traditional elements of Javanese culture.

Politically, the region has a pivotal place in Javanese history, from the time of its founding in 1755 as part of the Mataram Kingdom, through its prominent role in the fight for independence from the Dutch. The city itself served as the Indonesian capital from 1946 to 1950 when the Dutch reoccupied Jakarta in an attempt to reclaim its colonial control after World War II. After independence, its place and the role of the sultan, Hamengku Buwono IX, in the revolution were rewarded with its special status as a province of the Republic of Indonesia and the appointment of the hereditary sultan as governor for life. To this day it remains the only functioning sultanate in Indonesia, governed by a descendant of the hereditary rulers.1 While it has changed dramatically from a tightly structured, feudal, and autocratic society to a more democratic system, many traditional values dating from feudal times have not been completely washed away.

Currently, Yogyakarta serves as a regional commercial center and, with its many public and private colleges and universities, as an educational destination for the entire nation. It has changed since its founding more than 250 years ago, but it is still, as it was in 1755, an area concerned with formal religion, mysticism, and the quest for magical power. It also remains a symbol of Javanese power and culture. Given the dominance of Java in modern Indonesian history, Yogya by extension also has a central place in Indonesian society.

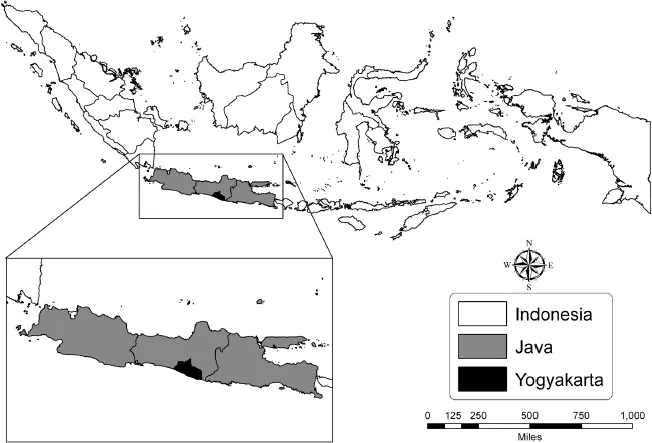

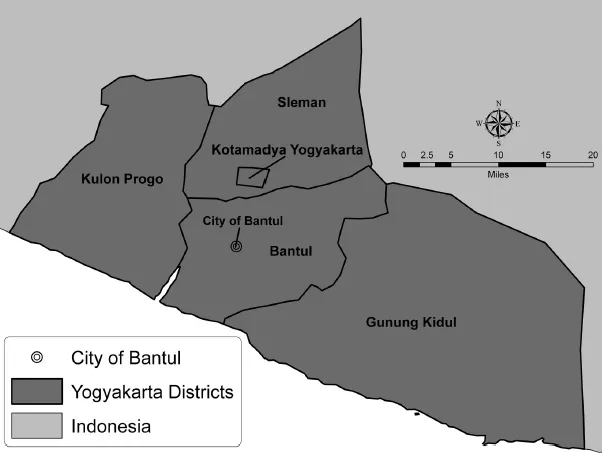

In the mid-1990s, at the time we initiated this study, the province had a population of more than three million people2 spread across four districts (kabupaten) and the municipality (kotamadya) of Yogyakarta, the provincial capital. Between the 1990 and the 2000 censuses,3 the population increased by only 7.2 percent, but shifted from primarily rural to majority urban (56 percent rural in 1990; 42 percent in 2000), marking this time as one of rapid population change (BPS 2004). As in all of Java, there is high population density, even in agricultural and rural areas. The two study villages selected were a more remote agricultural village located in the kabupaten, or district, of Sleman, in the northern part of the province; and a more urbanized village, located much closer to the center of urban life, in the district of Bantul in the southern part of the province.4 By the 2000 census, both districts averaged population densities of more than fifteen hundred persons per square kilometer (BPS 2004).

We chose these two villages for both theoretical and practical reasons. They each matched the requisite characteristics of being fairly typical rural villages that share Javanese culture and history. They have ethnically homogeneous and stable populations whose members have deep roots in their communities. Most villagers are practicing Muslims; and the two main Islamic organizations, Muhammadiyah and Nahdlatul Ulama (NU),5 are well-represented in both villages. But the villages varied dramatically in their degree of isolation from urban influence and the amount of state intervention involved in their economic development. One village remained more physically isolated, more agrarian, and slower to shed traditional social and cultural practices. The other was heavily influenced by its proximity to urban centers and the cultural influences of urbanization and modernization. They each had active women’s and community groups whose contributions to village life could be observed and studied, but the degree of state intervention in women’s activities also varied in the two villages. Finally, they both were accessible and receptive to our inquiries and had officials who were willing to give the necessary authorization to conduct field research.

Village Structure

In D. I. Yogyakarta, as in the rest of Indonesia, a village, or kelurahan (formerly desa), is an administrative classification that typically encompasses a series of rural settlements or subvillages called pedukuhan (formerly dusun),6 as well as the agricultural and open fields that are incorporated into its boundaries. Village lands may stretch for a substantial distance, and the pedukuhan, or subvillages, serve as the communities or neighborhoods that are most salient to daily life. In each village and subvillage, in addition to the individually owned plots, some of the fields are public lands whose use is politically or administratively allocated, usually as part or all of the compensation for kelurahan and pedukuhan officials. The village is administered by a head (now known as a lurah but formerly called a kepala desa or kades), who is directly elected by its residents for a term of six years.7 He is paid a salary and may also get use of village lands. Each subvillage (pedukuhan) also has a head known as kepala dukuh or dukuh, who formerly was appointed by district officials in consultation with the lurah,8 but now is elected following changes in the law after the end of the New Order. The dukuh is not paid a salary but is compensated with use of pedukuhan land. While the village lurah’s job is largely administrative and ceremonial, the tasks of the subvillage dukuh are more diverse. He (or she, although usually a man) is expected to be on call around the clock to deal with any community issues or residents’ problems. The intensity and more personal nature of this official’s responsibilities are indicated by the fact that most do not have a formal office; they use their homes to conduct their business.

Previously, there was no formal limit to the dukuh’s tenure; usually he served until he was ready to retire. Post-Reformasi, there is mandatory retirement at age sixty. The wives of village and subvillage officials also have important roles in village life. Although unpaid, they automatically become the heads of local women’s organizations, both in name and (usually, although not always) in fact, and they are expected to be active in community affairs.9

Village and subvillage officials act as gatekeepers to village life. As described previously and detailed further below, establishing relationships with the officials was an important part of gaining access to the field. In each village, we selected three subvillages to be the sites for our research. As in village selection, they were chosen for both practical and theoretical reasons. The former include access and accessibility—ability to establish relationships and rapport with both leaders and residents and the ability to get around and travel between sites. The primary theoretical issue was to make sure that subvillages fully represented the range of social and economic variation among village residents since patterns of spatial stratification varied. Some subvillages were homogeneous in the social and economic status of their residents; others had a mixture of classes. In order to provide a complete picture and enhance understanding of village life in each location, we include detailed descriptions of the subvillages used in the study. However, when reporting results, we generally make no distinction between subvillages, focusing on the much larger differences between villages.

Our field research was initiated during the mid-1990s in the last years of Suharto’s New Order government, with numerous subsequent return visits to collect new data and observe new developments. During this time there have been many changes in the political system, including village organization and administration. The New Order was a hierarchically organized and centralized administrative system that was tightly controlled from Jakarta, the capital. One of the biggest changes since the end of the New Order has been an ambitious decentralization plan that gives greater authority to local areas, most notably regions and districts, but also local communities. Shifting control to local areas has been a long, complex, and continuous process that has involved much jockeying for position and ultimate authority between regions, provinces, districts, and even local communities. By the mid-2000s, however, with the exceptions noted, the basic outlines of local Javanese village administrative authority had been determined.

The Village in Kabupaten Sleman

The district (kabupaten) of Sleman adjoins the city of Yogyakarta to the north and encompasses valuable property and affluent neighborhoods including Gadjah Mada University and other schools for which the area is known. However, Desa Danau,10 the study village in Sleman, was poor, relatively remote, and isolated, located twenty-five kilometers north of the city of Yogyakarta and five kilometers from the nearest main road connecting Yogyakarta to another midsize city, Magelang. In the mid-1990s, only small dirt roads connected village settlements or subvillages to the secondary and main roads. There was no public transportation directly to the subvillages, but it was available at a secondary road approximately one kilometer away. Work, marriage, and social activities were contained mostly within village boundaries, and travel to Yogyakarta was rare.

At the time we started the fieldwork, village records placed the population at 4,542 people in 1,026 households; 873 households were headed by males and 153 were headed by women. Women head households in the absence of an adult male because of the death of their spouse, divorce, desertion, or migration to other areas to seek employment.11 There were four primary schools located in the village, but no junior highs or high schools. The majority of the population (72 percent) had attended primary school. Education was valued and increased among younger cohorts, but the travel beyond the village required after primary school added expense and difficulty.

The village covers an area of 326,000 hectares, with 70 percent of the land used for agricultural production. Proximity to the active volcano Merapi creates fertile soil for agriculture as well as periodic crises for inhabitants. Village records are inconsistent and contradictory, but it is safe to say that agriculture is the primary occupational sector, employing as many as 70 percent of individuals who reported occupations12 and dictating the rhythms and schedules of village life. The raising of crops was also a source of local pride, status, social relationships, and values.

Small landowners predominated (720 persons, or 77.5 percent of those who are involved in agriculture), but their holdings were very small, averaging 2,500 square meters or one-quarter of a hectare of land or less, an amount that cannot supply adequate yield or income for most families. Almost 17 percent of the landowners owned between one-quarter and one-half hectare of land, while only one household had more than two hectares of land. Another 133 persons were land operators, and 76 people were farm laborers. Land operators are those who do not own land but have access to land by sharecropping or renting, while farm laborers do not have any direct control of land.

The farmers in this village usually independently chose the varieties and types of plants to be cultivated. Farmers’ groups were not very active and had little influence on agricultural production practices. Dry-season crops included vegetables and fruits such as eggplant, watermelon, green beans, corn, peanuts, and soybeans. An eggplant-processing factory constructed and owned as a joint Japanese-Indonesian venture provided a market for local produce and employment for some young villagers.

Other jobs were found in trade, services, and handcrafts. Agricultural products such as rice, tobacco, and vegetables dominated trade. The handicrafts sector consisted mostly of plaited mats, of which women were the primary producers. This activity was one of the lowest-income-generating activities, since each mat marketed at only Rp 125 to Rp 150 (6.25 to 7.50 cents at the value of the currency at the time). Because of this, many women participated in this activity as a secondary job. Multiple job holding and utilization of the labor of most household members was typical of this village.

Most of the population (4,400 people, or 96.9 percent) were Muslims; six persons (0.1 percent) were Protestants; and 136 persons (3 percent) were Catholics. According to many of the people in the interviews, before 1965 (the date of the failed bloody coup that ultimately brought Suharto to power), most of the people in the village were believers in Javanese mysticism. The village was among some regions in Yogyakarta where many disciples of Javanese religion were allegedly also members of or closely affiliated with the Communist Party. Since the Communist Party was banned after the failure of the attempted coup and most of its members were incarcerated or killed, people were apprehensive about being affiliated with the religion and, by extension, the party. Thus many adherents of the Javanese religion converted to one of the five formal religions accepted by the Indonesian government, and most of these converted to Islam for political expediency—Islam has the most followers in Indonesia, and Muslims were among the most active advocates for banning the Communist Party. Conversion to Islam was viewed as the safest way to avoid the accusation of being an ex-communist.

Despite the fact that village records did not indicate any current adherence to the Javanese religion, in some subvillages, traces of Javanese religion still persisted. This was very apparent in one of the subvillages where this study was conducted. Many people asserted that official religious organizations were not ver...