1 An Introduction to Angola’s Diamond Past

Paternalism, Professionalism, and Place

I admired the perfect organization of Diamang, I admired its industrial activity, I admired . . . the riches of its mines. But, more than the riches of the diamonds, I admired the richness of its souls.

—Dr. Vieira Machado, Portuguese Minister of the Colonies, following a 1938 visit to Diamang’s installations

Diamang has to be appreciated and judged not only . . . as a mining company, that extracts and sells diamonds. . . . This enterprise, as a consequence of the unique conditions in which it was created, and . . . from its isolation in relation to the rest of the colony . . . has evolved to be more an “enterprise of colonization” than a simple mining undertaking.

—Diamang General Assembly Meeting, 1959

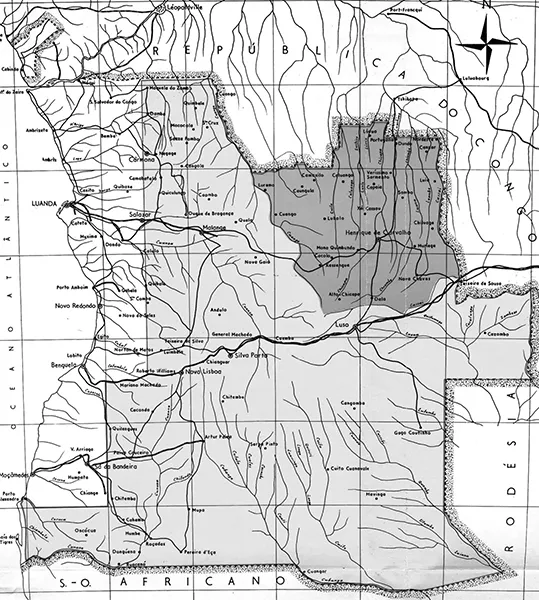

On the morning of November 4, 1912, prospectors found seven small diamonds near Musalala Creek in the Lunda region of the Portuguese colony of Angola. Less than five years later, in October 1917, international investors formed the Companhia de Diamantes de Angola, or Diamond Company of Angola (Diamang), to exploit the alluvial diamond deposits that had been identified in the interim.1 By 1921, in exchange for the rights to half of the company’s annual profits, the Portuguese colonial government had granted Diamang exclusive mining and labor procurement rights over a vast concessionary area in the northeastern region of the colony, roughly the size of the state of Oklahoma (map 1.1). Using these monopolies, the self-described “enterprise of colonization” was to become the largest commercial operator and leading revenue generator in the history of Portugal’s durable empire in Africa. Only the protracted Angolan Civil War (1975–2002), which followed the country’s independence from Portugal in 1975, was able to finally bring this industrial leviathan to its knees.2

It was on the backs of Diamang’s African labor force that the diamond enterprise generated its prodigious profits. Many local residents sought employment with the company, though others were forcibly recruited from throughout the Lunda region and brought to work on the mines. Together, they constituted the collection of “rich souls” that so impressed Dr. Vieira Machado following his visit to the company’s installations in 1938, as noted in the epigraph. Because Diamang demonstrated a preference for manpower over more costly machinery throughout its history, it aggressively pursued ever-greater numbers of laborers to staff its expanding operations. Consequently, from the commencement of mining operations in 1917 until Angolan independence in 1975, approximately one million African men, women, and children—who often traveled to the mines together as families—toiled for Diamang. Based on the company’s ability to procure and service this massive labor force, its operational zone became known in both European and African popular imaginations as um estado dentro do estado: “a state within the state.”

Following a tumultuous initial decade and a half of operations, a remarkable level of stability pervaded the company’s mines and mining encampments, as well as the thousands of kilometers of countryside that surrounded these installations. This relative quiescence stands in sharp contrast to the labor strikes, trade unionism, and intra-mine ethnic conflict that African mine workers elsewhere so commonly generated. Lunda remained conspicuously quiet even during the Angolan War for Independence (1961–75), while much of the rest of the colony erupted in violence. The central question that this book attempts to answer is: Why, in light of the demanding labor regime in Lunda, did African mine workers not adopt a more militant posture?

One way to interpret the absence of unrest on and around the mining installations is to attribute it to the repressive capabilities of Diamang and the colonial state. After all, the company was the largest and most powerful in Portugal’s African empire. It was, therefore, able to stipulate that the state, which often projected terror to compensate for severe human and material resource shortages, support its operational objectives.3 However, even after a variety of international pressures in the early 1960s—more than a decade before the conclusion of the company’s mining operations—compelled Diamang and the state to abandon corporal punishment and the forced labor scheme, stability reigned in Lunda. In fact, an inverse relationship existed between violence and productivity on Diamang’s mines: as the former decreased, the latter increased. While acknowledging that both real and potential violence contributed to keeping the regional population subdued—both on and off the mines—this book argues that a unique blend of company pragmatism, paternalism, and profits; African workers’ occupational and social professionalism; and Lunda’s geographical isolation were primarily responsible for the exceptional quietude.

It was during the 1930s that the confluence of these factors first began to produce this stability. Prior to this decade, many Lunda residents had violently resisted the company’s presence or fled ahead of labor recruiters. Similarly, Diamang’s African employees often deserted, while others only halfheartedly worked if they stayed. For its part, the company was offering only rudimentary accommodations, insufficient rations, and low wages, and mine overseers regularly assaulted laborers. However, as Diamang’s operations grew, company officials realized that they desperately needed the labor latent in the scarcely populated region. Moreover, as Diamang was unable to attract significant numbers of workers from beyond Lunda, its African employees were not expendable the way that they were on mines elsewhere on the continent and, in many cases, needed to be “recycled.” In response, Diamang adopted a pragmatic approach to its manpower needs. As part of this multifaceted strategy, the company improved working conditions, barred traditional authorities, or sobas, from its mines, and positioned Diamang to assume the paternalistic role of a “big man,” with all of the reciprocal structures and tropes with which Africans were familiar. Testimony from Joaquim Trinidade, a former employee, captures the company’s approach: “Diamang exploited the soil here, but also treated us [workers] well. So, Diamang was taking with one hand, but giving back with the other.”4

The origins of this “giving back” can be traced to the 1930s—paradoxically, at the height of the Great Depression. Although the global economy had collapsed, and the worldwide demand for diamonds had correspondingly plummeted, De Beers’s previously negotiated agreement to purchase Diamang’s output to maintain its (near) monopoly on rough stones continued to buoy the Angolan company’s revenues. While the global economy limped along, Diamang’s annual sales almost tripled over the course of the 1930s. Meanwhile, De Beers was forced to halt production and shutter diamond mines in South Africa and neighboring South West Africa (Namibia) during this same period. This extraordinary scenario is especially significant because the 1930s was the most pivotal, transformative decade in Diamang’s history, a period in which the company invested heavily in its health, food, and human infrastructures; as much of the continent suffered under the weight of the Depression, working conditions at Diamang were better than they’d ever been. If this newfound paternalism was rooted in the company’s pragmatic approach to staffing challenges, these ameliorative initiatives were facilitated by the ever-escalating revenues that it was enjoying. Indeed, it is almost inconceivable that Diamang was so profitable—growing output, revenues, and the size of its labor force year after year—in the context of such severe global economic devastation.

Exempt from all state taxes and duties and bolstered by the lucrativeness of Lunda’s high percentage of gem-quality stones (upwards of 80 percent), Diamang proceeded on very solid financial footing. From the 1930s on, it began using a portion of its wealth to upgrade services for its African workforce, including dramatic improvements in housing and health care; the introduction of a wide range of recreational activities; and an aggressive campaign to achieve full food security. Diamang also began dependably honoring the lengths of African laborers’ contracts, and mine overseers administered corporal punishment increasingly selectively. Collectively, these calculated measures proved to be highly efficacious, as each year the number of voluntary workers grew, and the company enjoyed uninterrupted increases in annual revenues.

Absent from this battery of corporate improvements were elevated wages. Over time, Diamang only reluctantly and minimally raised wages, such that, for example, in the 1950s its rates were among the lowest in the colony. Given its regional monopoly on labor, competitive wages were simply unnecessary. Consistent with its paternalistic approach, Diamang instead allocated funds to enhance the overall well-being of both its African workforce and the regional population via an array of health care initiatives and improved nourishment; for company officials, a healthy workforce (and labor pool) constituted a productive workforce. The combination of low wages and benefits aimed exclusively at regional residents explains Diamang’s inability to attract laborers from beyond Lunda. Low levels of monetary remuneration also ensured that minimal cash circulated in the region, money that in most other colonial mining contexts generated severe social disruption. By design, Diamang was to be the sole provider in Lunda.

Meanwhile, as the diamond enterprise consolidated its regional hegemony, Lunda residents-cum-mine workers determined that they, too, were “stuck” in a partnership with Diamang. In a region previously ravaged by the slave trade and most recently devastated and further depopulated by a collapse in rubber prices, sobas were no longer able to provide in ways that the company now could.5 In turn, regional residents increasingly began engaging with Diamang in a manner that signaled that they had conceded to the company the paternalistic “big man” role it had been seeking to assume. For example, as Diamang began improving conditions on its mines during the 1930s, African laborers’ productivity increased, while their absenteeism and desertion rates plummeted. I understand this form of strategic reciprocation as occupational professionalism, which stressed commitment and cooperation, while largely eschewing confrontation and subterfuge. More specifically, the constituent actions of this novel work ethic, which eventually became normative, included arriving to work on time; dutifully completing daily tasks; abstaining from work slowdowns, strikes, or other disruptive activities that would jeopardize production—the hallmark of mine laborers across much of Africa; and cooperating with co-workers across an array of potential social divides.

Testimony from Rodrigues, who began at Diamang in 1958, captures African laborers’ promotion and application of professionalism: “On our way to the mines, we had plenty of opportunities to talk and mingle with workers who had just finished. These workers provided us with both information and advice. They told us to work with força [effort]—if you had two meters of gravel to remove, then do it with força. And we did.”6 Women at Diamang also cultivated and embraced this occupational approach. For example, Mawassa Mwaninga, who first ventured to the mines with her husband in 1964, offered the following testimony. “I had a baby girl while at the mines, in a company hospital. The branco [Portuguese] told me I didn’t have to work while I was pregnant, but I did anyway—all the way up until five days before I gave birth! I received a week off afterwards, but was still being paid. After this, I went back to work with the child on my back.”7 Both Rodrigues’s and Mwaninga’s words powerfully convey the occupational commitment and focus that the enterprise’s African laborers so consistently displayed.

As there had been no colonial precedents in Lunda before Diamang’s arrival, it took workers time to formulate new conceptions of power, responsibility, and expectation in the context of labor-management relations on the mines. As the company began cultivating a more agreeable environment in the 1930s, African laborers began infusing the Western (corporate) notions of time and work that they had been internalizing with their own notions of social reciprocity. These complementary developments enabled workers to realize both their personal expectations and professional objectives.

Beyond forging a particular occupational approach, African laborers also adopted an assortment of social improvement strategies away from the work site, which were, in almost all cases, not intended to undermine Diamang’s bottom line. For example, family members regularly accompanied recruits to the mines and, once there, creatively distributed workloads among themselves and reached across a range of social divides to befriend and fraternize with fellow residents in mine encampments, as well as with members of nearby communities who were otherwise unaffiliated with Diamang. I understand these actions and behaviors to be constitutive of social...