![]()

1

The Value of Culture

Congolese Art and Belgian Colonialism

FOR MOST of the colonial period, the Museum of the Belgian Congo was the most visible presence of the empire in Belgium and one of the a major avenues through which Belgian citizens got to know their colony. Its neoclassical and marble halls filled with its zoological, mineralogical, and man-made “wonders” represented the colony. During the 1950s, the museum received between 141,800 and 197,859 visitors a year, the equivalent of up to 2.3 percent of the Belgian population. This made it one of the most visited museums in Belgium.1

This chapter lays out how representations of Congolese cultures were produced and projected at the museum, and the ways in which these intersected with and helped shape colonial ideologies. The process whereby Belgium became the custodian of a large museum collection of Congolese material is explored, and the chapter explains how a fragmented and varied process of collection was translated into seemingly coherent images of Congolese culture and bodies of knowledge.

I argue that the very guardianship of the museum’s collections became integrated into late colonial justifications for Belgium’s colonial presence in the Congo. This relied on two processes: the production of new values and meanings for African objects as art and the accompanying construction of Congolese cultural authenticity as endangered. This meant that Congolese art, eventually transformed into an exceptional resource with cultural and economic value, came to have its place in the mise en valeur narrative about the colony presented to the museum audience.2 The “endangered authenticity” projected upon the communities that originally produced these objects also provided an extra justification for Belgium’s continued presence in the Congo: the protection and guardianship of “traditional” cultures.

THE MAKING OF A COLONIAL MUSEUM AND THE CHANGING FACE OF COLONIALISM

Scientific exploration and the origins of the Belgian Congo are inextricably connected. Masking his imperial ambitions as scientific interests, Leopold II in 1876 organized the International Geographic Conference, where the Association Internationale Africaine (International African Association—AIA) was created, ostensibly to promote the exploration of the African continent. Simultaneously, Leopold II hired Henry Morton Stanley, a Polish-American newspaper reporter turned explorer, to explore the Congo River basin and secure allegiance from local leaders in order to thwart other European interests in the region. Having deftly manipulated those interests, Leopold II succeeded in securing recognition as the sovereign of the Congo Free State at the Berlin Conference of 1884–85. From then on, the area was essentially the private property of Leopold II, although representatives of the Congo Free State would not bring the entire area under their control until early in the twentieth century.3

Although Leopold II firmly believed in the area’s economic promise, he was not able to tap Congo’s resources until the allocation of exploitation rights to a number of regional concessionary companies, as well as to the “Royal Domain,” which remained directly under Leopold’s control. The representatives of these companies (which included the Anglo-Belgian Rubber Company and the Société Anversoise) and state agents in the Royal Domain received commissions on the amount of product (initially ivory, but eventually mostly rubber) they extracted.4 With no state regulatory controls, this arrangement led to widespread abuses at the expense of the local population while generating great wealth for the Congo Free State and its monarch.5

The creation of the Museum of the Belgian Congo was deeply intertwined with the colonial project of Leopold II. As early as the 1880s, the Belgian king seized on the potential of colonial exhibitions for the promotion of empire. These exhibitions served two purposes. On the one hand, they were intended to stimulate Belgian (and international) interest in the commercial opportunities of the area.6 To that end, extractive products such as ivory, tropical woods, and rubber as well as agricultural products such as cotton, coffee, and cacao were most prominently displayed. Displays on the natural sciences emphasized the diversity of fauna and flora, while geological maps and displays emphasized potential mineral resources. Aside from attracting investors and businesses to Congo, the other goal of these exhibitions was to convince the general Belgian population of the value of having a colony. While economic potential was certainly important in this respect, the organizers of these colonial exhibitions also emphasized the civilizing work there was to be done in the colony, organizing and displaying ethnographic material to this purpose.

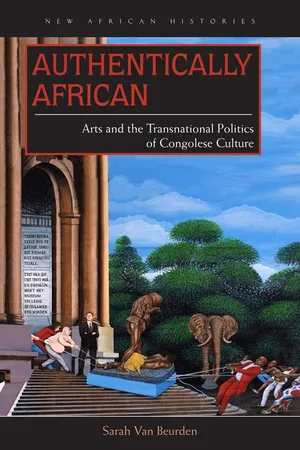

For the international exhibition of 1897 Leopold II opened a “Palais des Colonies” in the royal park in Tervuren, near Brussels.7 The success of the exposition (1.2 million visitors in six months) led to its becoming a permanent exhibition in 1898, and soon plans were drawn up to construct a real museum building. Leopold II envisioned a park, or a “small Versailles,” with a museum, spaces for the exhibition of Asian art (another region on which he had set his imperial ambitions), extensive gardens, and an international school. The design of the new museum was entrusted to the Parisian architect Charles Girauld, and construction began in 1906, although the elaborate scale of the project was reduced to the building of a museum.8

From the beginning, the museum’s mission was “to ensure the promotion of the colony, to spread knowledge about all its aspects and to encourage vocations for colonial careers.”9 The Belgian population had historically been apprehensive with regard to its king’s colonial undertakings and worried about “their sons and their cents.”10 Whatever the degree of nationalism among Belgians, in most cases it did not extend to a willingness to travel to Central Africa or even to contribute financially to that adventure.

Tervuren’s founding between 1897 and 1910 came late when compared to the first generation of ethnographic museums, founded beginning in the 1840s, but it coincided with the wave of new and renewed museums of ethnography opening across Europe in the late nineteenth and first part of the twentieth centuries. The creation of these museums was often driven by anthropologists’ desire to elevate their discipline and to create spaces with both an academic and a broader educational purpose.11 Tervuren, however, was not intended as a museum of anthropology or ethnography but rather as a museum for the promotion of colonialism. Empires and museums shared close ties throughout Europe, but this founding purpose and oversight by the Ministry of Colonies set the museum of Tervuren apart.

While Leopold II promoted the idea of empire to the Belgian population, growing international critiques of the abusive system of rubber exploitation threatened Leopoldian rule in Central Africa. Spurred by protests from some of the Protestant missionaries, British accusations regarding the abuses began circulating widely in 1904. The widespread attention and international hostility generated by E. D. Morel’s Congo Reform Association and the damning Congo report of British consul Roger Casement made the existing arrangement untenable for the monarch. As a result, the Belgian government—although not without internal debate—took over the colony, and its museum, in 1908.12

By the time the newly designed museum building opened in 1910, the colony—and its promotion—had become a matter for the Belgian state.13 Little had changed, however, in the Belgian population’s lack of interest in the colony, and the Museum of the Belgian Congo would become one of the most important tools in combating this indifference. A visitor to the museum in 1910 would first circulate through natural science displays before entering the halls housing the ethnographic material, followed by an area devoted to history that included a section on “political and moral sciences,” documenting the influence of the West, and Belgium in particular, in the Congo. The visit finished with a tour of displays emphasizing the colony’s potential to generate income for its colonizer. A visit was intended to induce wonder at the riches of the colony, and pride at the role of Belgium as a “civilizer.”

Meanwhile, the Belgian state attempted to create a new kind of colonial system in Congo that would distance it from Leopoldian absolutism in the eyes of the international community, but even with an expanded colonial administration and colonial reforms, forced labor practices and violent suppression of African resistance persisted. The numbers of (Catholic) missionaries, civil servants, and entrepreneurs grew steadily, particularly after World War I.14 The Belgian colonial system rested on three “pillars”: the colonial companies; the (Catholic) missionary congregations, responsible for the “civilization” of the Congolese population, which in practice meant a monopoly on the religious, educational, and health systems in the colony; and the colonial administration, backed up by the Force Publique, or colonial army. The economic sector expanded and diversified after 1908—a cash crop economy developed, but the exploitation of the colony’s mineral resources, including gold, copper, and diamonds, was central, and it relied on large-scale regional migration for its labor force.15

The colonial state’s indigenous politics were characterized by “prescriptive, administrative and judicial regulation of conduct [of the Congolese population] developed along with other forms of social engineering” that targeted things like hygiene, housing, and infrastructure development. The territory was divided into administrative territories and districts with civil servants assigned to each, but there were also efforts to integrate some of the local power structures into the colonial system. For example, local “chiefs” (known as chefs médaillés) amenable to the colonial power system were appointed by the colonial regime. Given their role as facilitators of colonial power, they did not always enjoy the respect of the population.16

The need for reform of the colonial system, overly reliant on large corporations and missionary groups, was apparent by the late 1930s, but World War II was the real catalyst for change. Not only was Congo the only “free” Belgian territory during the war, it also made considerable contributions to the Allied effort in the form of raw materials, especially uranium (most famously including the uranium used in the American atomic bombs dropped on Japan). Increased awareness of the great economic value of the colony’s resources invigorated the Belgian state’s desire to “modernize” the colonial system and increase its hegemony in relation to the powerful companies and missions.

The Belgian state also hoped that a “different” kind of colonial regime, which, in theory, applied some of the principles of the Belgian welfare state, would undermine any nascent independence movements. Belgian belief in its “welfare colonialism” remained strong, which explains why many Belgians were caught completely off guard by events in the colony in 1959.17 Of course, postwar modifications to colonial regimes were not unique to Belgium. Both France and Great Britain attempted to sustain their empires in Africa by implementing limited reforms with the goal of placating the colonies’ increasing demands for participation in the political, social, and economic life.18 The impact of Belgium’s “welfare colonialism” was limited and did not alter the political structures in the colony. Instead, the colonial government believed that social reforms aimed at diminishing the racial segregation between the colonizers and their subjects in daily life and promoting a class of évolués (“evolved” colonial subjects) would be sufficient to ensure the allegiance of the Congolese population.19 Additionally, increased construction of urban and transportation infrastructure and the limited introduction of social welfare benefits for the small class of Congolese wage earners sought to develop the loyalties of urban populations.20 These efforts, however, ignored the rural underdevelopment that defined the communities in which most Congolese people lived.21

Crucial to selling this renewed colonial vigor to the Belgian population was the idea of mise en valeur, or the value the colony’s exploitation could generate for the mother country.22 As it had before, the Museum of the Belgian Congo played a prominent role in the promotion of the promise of the colony to Belgians. As I will argue next, in the postwar era and particularly in the 19...