- 234 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Psychiatrist, philosopher, and revolutionary, Frantz Fanon is one of the most important intellectuals of the twentieth century. He presented powerful critiques of racism, colonialism, and nationalism in his classic books, Black Skin, White Masks (1952) and The Wretched of the Earth (1961). This biography reintroduces Fanon for a new generation of readers, revisiting these enduring themes while also arguing for those less appreciated—namely, his anti-Manichean sensibility and his personal ethic of radical empathy, both of which underpinned his utopian vision of a new humanism. Written with clarity and passion, Christopher J. Lee's account ultimately argues for the pragmatic idealism of Frantz Fanon and his continued importance today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Frantz Fanon by Christopher J. Lee in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Martinique

There were some who wanted to equate me with my ancestors, enslaved and lynched: I decided that I would accept this.

—Black Skin, White Masks1

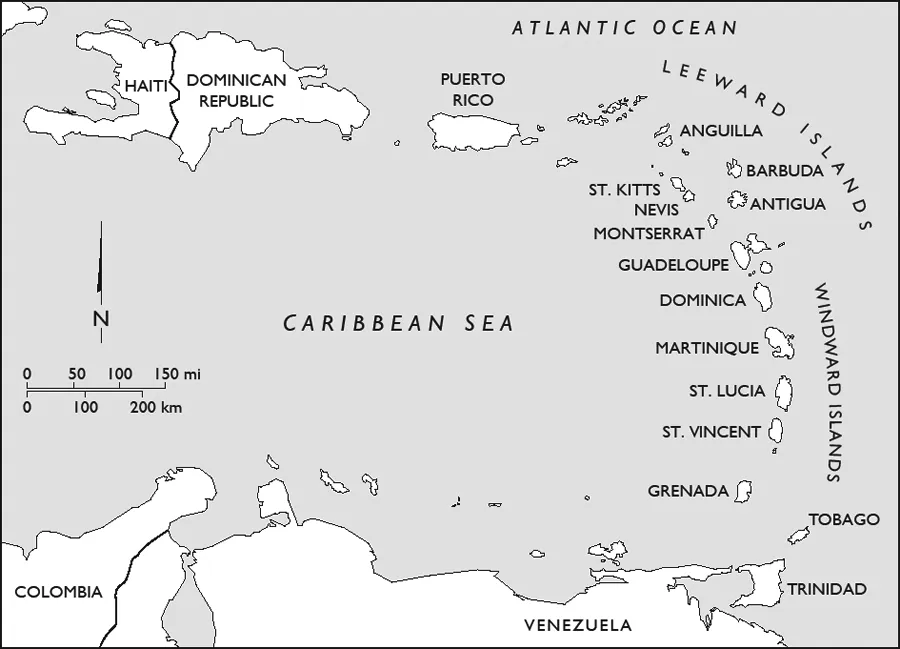

Frantz Fanon was born in Fort-de-France, the capital of Martinique, on July 20, 1925. Martinique is often a cipher in many studies of Fanon, treated merely as a place of origin. But its deep history fundamentally informed his identity and shaped his ambitions. A small island of approximately 1,128 square kilometers (436 square miles) located toward the southern reaches of the Lesser Antilles near South America (see map 1.1), Martinique’s size and geography suggest a peripheral status within the French Empire. However, contrary to these surface qualities, the island experienced the firm entrenchment of French rule and influence beginning in the seventeenth century. Local indigenous societies were quickly subsumed through conquest, with European settler and enslaved African communities defining Martinique’s political and cultural life. French control took hold in a way that reflected metropolitan concerns for maintaining authority and legitimacy in a geographically distant, yet economically important, territory.

Map 1.1 The Antilles and the Caribbean.

These long-standing conditions elucidate the complex search for political and cultural alternatives by figures like Fanon, Aimé Césaire, and Édouard Glissant, generating a particular Antillean discourse (discours antillais), to invoke an expression of Glissant’s.2 Martinique remains a part of France to the present day—an overseas department (département d’outre-mer) like Guiana in South America, Mayotte and Réunion in the Indian Ocean, and Guadeloupe, also in the Caribbean. Indeed, it is a historical irony that Césaire and Fanon, as vocal critics of colonialism, originated from a place that did not ultimately achieve independence like other French territories in the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Still, this basic fact and the deep-seated French-ness in Martinique also explain their motivations, underlining how and why such a small place produced vital thinkers who confronted the paradox of French rule that promised political and social equality in principle, but denied it in practice. Racism, based on a history of black enslavement, underpinned this contradiction.

Slavery and Its Enduring Legacies

As with many European colonies, the French acquisition of Martinique was prompted by competition with other imperial powers, as well as its economic potential. Originally occupied by indigenous Arawak and Carib communities, Martinique was identified and mapped by Christopher Columbus (1451–1506) in 1493. France claimed it almost 150 years later in September 1635, when a group of French settlers established Saint-Pierre (or St. Pierre), having been pushed off the neighboring island of St. Kitts by the British. But Martinique’s political status remained uncertain during the next two centuries, with the British occupying the island on several occasions. Only after the Napoleonic Wars (1803–15) did French rule stabilize, lasting to the present day. Still, by the early eighteenth century, slavery had been established within the island’s economy, following the 1685 promulgation of the Code noir—the French legal decree by King Louis XIV (1638–1715) that formalized slavery and restricted the freedom of emancipated blacks. Coffee and especially sugar became the key commodities produced by slaves for export to Europe—an extremely lucrative trade, such that France gave up its sizeable Canadian possessions (including present-day Quebec and Ontario) at the end of the Seven Years’ War (1756–63) against the British, in order to retain the far smaller territories of Martinique and Guadeloupe.

Though Fanon was born well after abolition, the history of slavery on Martinique is vital to understanding his personal origins, the racism he fought against, as well as the anticipatory role that slave emancipation had for ideas of anticolonial liberation. Enslavement incurred a form of social death, to use sociologist Orlando Patterson’s expression, which left enduring legacies of dehumanization and lower-strata status.3 The practice of slavery on Martinique took the particularly harsh form that characterized sugar production across the Caribbean. Its brutality would have lasting political, economic, and intellectual effects. First introduced to the Western Hemisphere by Columbus, sugar cultivation spread around the Caribbean over the next several centuries, sparking economic growth across the Atlantic world. Indeed, as argued by scholar-politician Eric Williams (1911–1981), this commodity generated enough surplus wealth to help initiate the Industrial Revolution in Europe during the nineteenth century.4 The triangle trade that sent slaving ships from Europe to West and Central Africa, slaves from Africa to the Western Hemisphere, and sugar and other slave-produced commodities—such as cotton, tobacco, and coffee—to Europe created a cycle of commerce that altered European consumer tastes, encouraged imperial expansion, and transformed the political histories of many African states, which both participated in and fell victim to the slave trade. No less significant, it fundamentally changed the demography of the Americas, bringing millions of African people north and south of the equator. African slaves in turn profoundly shaped the economies, cultures, and politics of the Western Hemisphere. But they did so in the wake of the Middle Passage—the westward journey of slave ships across the Atlantic—during which millions died from disease, malnutrition, and physical mistreatment.

Violence and mortality continued to define the lives of those who arrived. The presence of death in its spectral and actual forms circumscribed the lifeworlds of those enslaved. Disease and the threat of corporal punishment caused constant anxiety. The backbreaking nature of cultivating, harvesting, and processing sugarcane weakened physical regimens and shortened the lifespans of many. Practices of commemoration subsequently emerged that sought to preserve cultural tradition and senses of African identity, in order to resist the overwhelming nature of enslavement, geographic dislocation, and colonial disempowerment.5 These customs also insured that slavery and its violent history would never be forgotten in popular memory. Although the abolition of slavery in Martinique in 1848—coincidentally, the same year France claimed control over the territory of Algeria—preceded Fanon’s birth by almost eighty years, the legacy of slavery and its dehumanization continued to ripple up through the twentieth century, marking Fanon’s history and social status as it did for so many other black men and women in Martinique and throughout the Americas. Fanon never addressed slavery in his own writing with the same rigor as other topics.6 But its pervasive latency in Martinican society unquestionably informed his political outlook, as indicated by the epigraph for this chapter.

Balancing this history of racial oppression was an overlapping history of rebellion. The French Revolution (1789–99) affected the Caribbean, with the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) being the most significant political outcome in the region—a world-shattering revolt led by Toussaint L’Ouverture (1743–1803) along with other former and rebel slaves, who embraced the rights of liberty, equality, and fraternity as espoused by the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen (1789). The meaning of the Haitian Revolution should not be underestimated. Not only did it signify the global reach of the French Revolution, but it vividly underscored the capacity of African slaves to resist their bondage and establish a new political order, to the shock and fear of slave owners throughout the Western Hemisphere. The Haitian Revolution remains the only slave revolt in history to result in the founding of a new sovereign state. This overwhelming fact generated immediate anxieties that similar uprisings could be staged north in the United States and south in Latin America. But the meaning of Haiti has equally extended to the twentieth century, becoming an early symbol of anticolonial revolution as argued by the Trinidadian intellectual C. L. R. James.7 For Martinique, the French Revolution resulted in citizenship rights being extended to persons of color, with slavery itself abolished in 1794. However, a British takeover of the island the same year and the Napoleonic Wars prolonged slavery’s slow death until 1848. Nevertheless, Martinique, similar to Haiti, experienced tension and debate over slavery and citizenship rights. This regional political tradition of resistance informed the views of Martinicans.8

Yet, unlike Haiti, the end of slavery in Martinique did not spell the end of colonial rule. It did grant legal citizenship rights to the island’s inhabitants—Fanon was a French citizen by birth. But this political failure and the continuities between enslavement and colonialism were not overlooked by Martinique’s intellectuals, including Fanon. In Black Skin, White Masks, he deftly insinuates this perspective, writing, “I am not the slave of the Slavery that dehumanized my ancestors.”9 Fanon instead felt indentured by his racial status and the cultural chauvinism he faced under French colonial control. This prejudice was both local and imperial in its dimensions. The basic structure of inequality in Martinique along lines of race and class was forged in the crucible of slavery and continued up through the early twentieth century—a hierarchy reinforced by demographic numbers and white political and economic control.

The population of slaves in 1696—roughly a decade after the Code noir decree—approximated 13,126 people out of a total population of 20,066. By the time of emancipation in 1848, slaves numbered 67,447 people out of an overall population of 120,357.10 Slaves therefore remained in the majority for more than 150 years. But while these figures indicate a stable population ratio over time, they do not reflect the full magnitude of racial difference on the island. Many of those in the nonslave minority were also of African descent, either as freed slaves or gens de couleur libres (“free people of color”), a group principally comprised of métis (persons of multiracial background) born from relationships between European men and slave women. Though tensions of race and status emerged between these different groups, an overwhelming nonwhite majority existed, persisting to the present. Approximately 90 percent of Martinique’s population today is of African descent.

This racial demography combined with the social hierarchy that slavery and colonialism constructed—with a white minority occupying the top tier—set the stage for Fanon’s worldview: a perspective defined by belonging to a majority, yet one unjustly limited by racial discrimination. Landownership stayed in the hands of a ruling white plantation class after emancipation. Labor continued to be provided by black Martinicans, augmented by indentured immigrants from India, primarily Tamils from French-controlled Pondicherry. As a result, political power remained among elite whites and békés—Creole whites who descended from the original French settler community.11

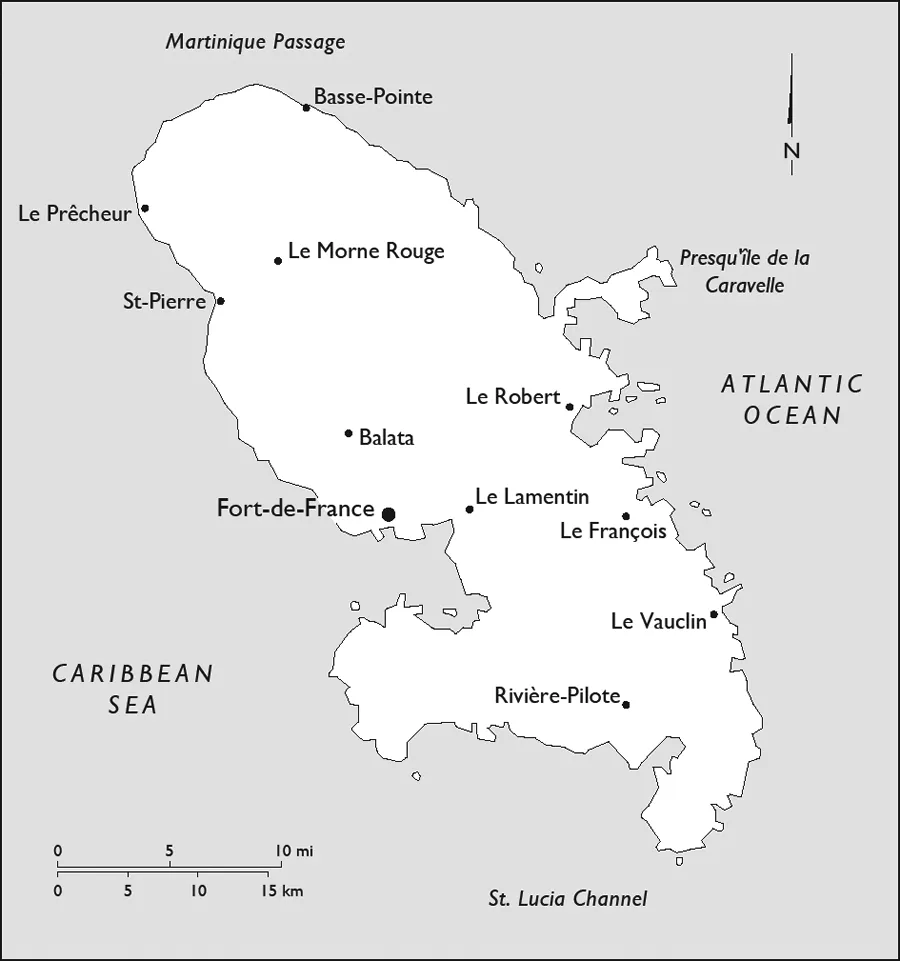

Middle-Class Life in Fort-de-France

The recorded history of the Fanon family starts in the 1840s with his great-grandfather, who was the son of a slave but himself a free man. Fanon’s great-grandparents and grandparents owned small farms. His parents, Félix Casimir Fanon (1891–1947) and Eléanore Médélice Fanon (1891–1981), lived in urban Fort-de-France, working as a civil servant and shopkeeper, respectively (map 1.2). They had eight children, Frantz being the fifth. His mother was métisse—which may have granted Fanon some status, due to Martinique’s racial politics—with part of her family being from Strasbourg in the Alsace region along the border of Germany and France. The Germanic name “Frantz” is understood to be a gesture toward this familial past. Given the professional occupations of his parents, Fanon was born into relative privilege—a first-generation, middle-class milieu—even if the degree of affluence possible in Fort-de-France at the time was limited.12

The population of Fort-de-France approximated 43,000 people during the 1930s, a decade after Fanon’s birth, signaling the small scale of its economy and urban life generally. While it maintained all the essentials of a Caribbean port city with commercial facilities and a French naval installation, business activity was minimal and largely local after the decline of sugar’s profitability at the end of the nineteenth century. Fort-de-France had long been Martinique’s center of government, but the historical and cultural hub of the island had been its first settlement, Saint-Pierre, once known as “the Paris of the Caribbean.” Saint-Pierre experienced a cataclysmic downfall in 1902 with the volcanic eruption of Mount Pelée that emitted a cloud of toxic gas, killing 30,000 people in its wake. Fort-de-France consequently swelled in size in the decades that followed. Urbanization delivered a mix of benefits and drawbacks. The promise of work and financial opportunity for Martinicans without land competed with everyday problems of poor living conditions, inadequate sanitation, and disease due to an expanding urban population. Smallpox, leprosy, and tuberculosis were common.13

Map 1.2 Martinique.

Fanon himself escaped the worst of these conditions. His family accrued enough wealth for household servants, private schooling, and a second home. Fanon never wrote about or discussed this relative affluence. Indeed, Alice Cherki, in her memoir of Fanon, recalls his persistent privacy, writing, “Every time Jean-Paul Sartre wanted to know some particular concerning Fanon’s life, Fanon avoided answering by dismissing the information as ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- A Note on Translations and Editions

- Introduction. Unthinking Fanon: Worlds, Legacies, Politics

- 1. Martinique

- 2. France

- 3. Black Skin, White Masks

- 4. Algeria

- 5. Tunisia

- 6. The Wretched of the Earth

- Conclusion. Transcending the Colonial Unconscious: Radical Empathy as Politics

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index