![]()

1

The First Films, 1896–1908

Itinerant Exhibitors: Lumière in the Austro-Hungarian, Prussian, and Russian Empires

THE TRAVELING EXHIBITORS WHO INTRODUCED motion pictures to the area eventually brought their demonstrations to all the main cities of the partitioned lands and to many of the small towns as well. Various factors influenced their choice of routes and stopping places. Railway lines allowed the exhibitors to move among the small towns along the routes from Warsaw to other cities in the Russian Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia. Rail connections in the eastern part of the Russian partition were less substantial, however, and poorly maintained links to Kraków, L’viv, and other towns of the former commonwealth hindered travel. Electrification, too, came about only gradually. Inhabitants of cities in the Prussian partition were receiving limited benefits from electricity by the end of the nineteenth century, while the process took even longer in the cities of the Russian and Austro-Hungarian partitions. Lights came on slowly in the countryside of each region. Local variations in population and wealth likely influenced exhibitors’ opportunities, as well. Urbanization opened possibilities for exhibition to larger audiences. Warsaw and its suburbs, for example, experienced immense growth between 1890 and 1910, when their total population climbed to almost one million. Levels of wealth were lowest in Galicia and highest in Prussia.1 Moreover, although higher levels of education accompanied urbanization, literacy spread slowly. In 1897, Warsaw’s illiteracy rate of 41 percent among men and 51 percent among women was lower than the rates in other large cities (in Łódź, for example, 55 percent among men and 66 percent among women), and much lower than the 69.5 percent overall rate in the Russian Empire.2

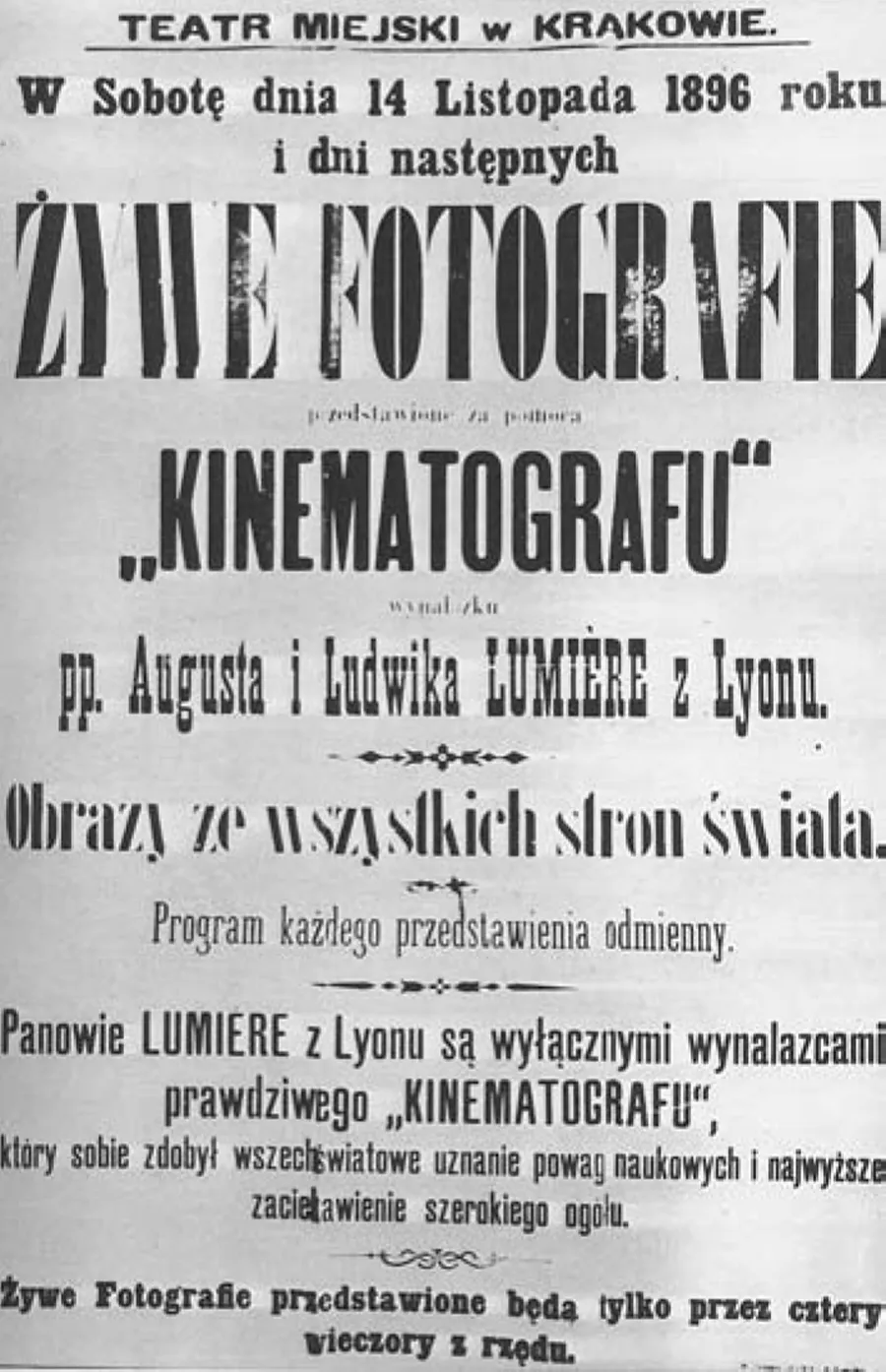

An advertisement for an early demonstration of the Cinématographe. Biblioteka Narodowa

The first demonstrations of “a theater of live photography” took place in Warsaw at the end of 1895 and the beginning of 1896, when Thomas Alva Edison’s Kinetoscope (or, perhaps, a counterfeit version of it) appeared first on Niecała Street and next in the Panopticum on Krakowskie Przedmieście Street.3 In July of that year, exhibitors lured audiences to an enormous ballroom and meeting space on Krakowskie Przedmieście Street with a (presumably counterfeit) copy of Louis and Auguste Lumière’s patented Cinématographe, an apparatus constructed to record, print, and project films that had been demonstrated for the first time in Paris in 1895. They chose images of people walking along the street, a fire engine in operation, dancers, and cat pranks for this first demonstration. This makeshift cinematograph disappointed the Warsaw patrons, who complained that the presentation was of poor quality and that its exhibitors were not organized or competent in handling the new technology. The viewers also remarked that it was unoriginal in light of other inventions of the time. One commentator writing in Kurier warszawski (Warsaw Courier) in 1896 claims that the invention

would have been awe-inspiring, if in the age of telephones and phonographs there could be anything awe-inspiring. It is the cinematograph, a combination of photography and electricity. . . . The thing is unusual in itself, very interesting and worthy of admiration, but the apparatus, which is operated by a Warsaw entrepreneur, does not work properly. Because we are not able to compare, we cannot, of course, conclude whether this is the fault of the still imperfect idea, or the apparatus itself, which acquainted us yesterday with a solution to the problem of movement.4

In L’viv, Galicia, entrepreneurs presented the first program of short films in September 1896. It is not clear whether the equipment featured Edison’s Vitascope, Kinetoscope, or a counterfeit, although the last is most probable.5 According to historian Andrzej Urbańczyk, the first exhibition included a separate demonstration of a related invention, the phonograph. The performances took place in the Grand Hotel and at a hostel for workers located in the same section of the city. Underscoring the dubious aspects of this presentation, the program advertised an unlikely slate of films that combined, for example, the Edison Company’s Chinese Laundry Scene (1894) and Annabelle Serpentine Dance (1894) with the Lumière production L’Arrivée d’un train à La Ciotat (Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat, 1895).6 Accounts of the first screenings give the impression that audiences arrived pessimistic, skeptical, and certain that the presentation would be second-rate, and they received no surprises. Writing some thirty-four years later, novelist Juliusz Kadren-Bandrowski recalls one of the first demonstrations in the city: “Some people said during the intermission that in spite of everything, the show would probably not make it to the end because, eventually, something must go wrong. Still others were certain that it all had to be some kind of false imitation and, sooner or later, it would turn out to be a devilish hoax.”7

On November 14, 1896, the first demonstration of the patented Cinématographe took place in Kraków’s Community Theater. The Galician city of Kraków—home to fewer than a hundred thousand people at the turn of the twentieth century—supported one of the most active theatrical traditions, including traditional stage theater, magic lantern shows, and demonstrations of other cerebral curiosities, in the partitioned lands. Lumière exhibitor Eugène Joachim DuPont brought the Cinématographe to Kraków from Vienna and advertised the demonstration in a local newspaper, Czas (Time). He re-created the program of twelve short films that had been shown during the famous first demonstration of the apparatus at the Grand Café in Paris eleven months earlier. It included, among others, Repas de bébé (1895), L’Arrivée d’un train à La Ciotat, La Charcuterie mécanique (1895), Arroseur arrosé (1895), and Quarrelle enfantine (1896). So successful was the process this time that, after its solo premiere, the short films were added to the end of regular theater performances as a bonus for audiences. The program changed often, and projections were not regular; but in December 1896 and sporadically throughout 1897, around forty short films were shown in Kraków.8 Additions to the program included Partie d’écarté (1895), Photographe (1895), Dragons traversant la Saône à la nage (1896), Enfants pêchant des crevettes (1896), Démolition d’un mur (1896), and Les Bains de Diane à Milan (1896). The virtual itinerary of the Kraków audiences included Madrid, Paris, Milan, Tyrol, and London, but nowhere outside western Europe. Although the quality of the projections was poor, reviewers expressed the astonishment and intrigue that audiences felt when they saw moving images of trains, people, and, especially, ocean waves.

Demonstrations of the Cinématographe soon followed in other cities in the partitioned lands, including Poznań in the Kingdom of Prussia and Warsaw in the Russian Empire. In the Russian partition, demonstrations took place in storefronts and restaurants. The railway that connected Warsaw to smaller towns in the region connected it to western European cities, as well, making the city a rest stop for many traveling entrepreneurs. Because it was relatively large and easily accessible, Warsaw was the most logical place for the new industry to take root. Although urban theaters and cafés held exhibitions, many shows took place in outdoor venues, such as the circus, during the warm season. According to film historians Władysław Banaszkiewicz and Witold Witczak, projections were held at twilight during almost every summer event in Warsaw at the turn of the century.9

The history of cinema in the small city of Bydgoszcz in the Kingdom of Prussia offers an exceptional opportunity to reflect upon issues of film, language, politics, and cultural identity. Scholars know little about the first exhibitions in Bydgoszcz. Although it is clear that itinerant exhibitors appeared in the city in April 1897, the names of those first exhibitors and the titles of films shown in the first programs are unavailable—but information on traveling exhibitors in small cities and towns is always difficult to find. What makes Bydgoszcz interesting is its character as a meeting point for Polish and German cultures. The majority of people in Bydgoszcz at the turn of the twentieth century spoke German and identified with the cultures to the west rather than those to the east, even though Poles considered the city an inseparable part of Polish national identity. Not surprisingly, residents may have had a perspective on the subjects of itinerant exhibitors’ programs that differed from that of residents of other cities.

In Filmowa Bydgoszcz, 1896–1939 (Filmic Bydgoszcz, 1896–1939), Mariusz Guzek suggests that the beginnings of a local film culture can be found in the photographic exhibits at the Kaiser Panorama located on Fryderykowska Street (now Marszałka Focha Street). Guzek explains that through the subjects of these exhibits—he cites Constantinople, the Rhine Valley, Cyprus, and Syria as examples—the residents of Bydgoszcz grew accustomed to seeing photographic representations of different parts of the world on a regular basis. He writes, “Still images, just like the later live photographs, affected the imagination, satisfied the curiosity associated with the unattainable spheres of life, and supplied entertainment.”10 Guzek notes that the central location of the first projections of the Kinetoscope (or Vitascope) in a hall on Berlinerstrasse (now Świętej Trójcy Street) was chosen on purpose, as it was one of the few public places in Bydgoszcz visited by both Poles and Germans.

While the Lumière brothers’ films took center stage in the Russian Empire, American picture shows made their way through the partitioned lands in the Kingdom of Prussia. Zygmunt Pogorzelski, a Polish exhibitor, showed the Lumières’ L’Arrivée d’un train à La Ciotat for the first time only in 1902 at an outdoor festival on the outskirts of Bydgoszcz (where a majority of the town’s Polish inhabitants lived).11 The reason for this division may lie with historical ties dating to the Romantic period between speakers of the Polish and French languages in the Russian Empire, which made French films attractive, and with a long-standing struggle for power between speakers of the Polish and German languages in the Prussian partition, which led Polish speakers to shun German films. Linguistic and cultural affinities—or antipathies—thus reflected political alliances and rivalries. That these political-linguistic relationships affected even the earliest exhibitions of silent films shows the extent to which early exhibitors regarded cinema as an international business venture based as much on established political practices as on creative entrepreneurship and a sense of adventure. From the outset, exhibitors found themselves—willingly or not—part of the political landscape.

During the five years that followed the debut of the Cinématographe in Kraków, entrepreneurs moved from town to town throughout the partitions to offer demonstrations of their short films. In this time of actualités (short nonfiction films, such as travelogues, sports films, and news event films), reenactments, short fictionalized historical films, and one-act comedies, programs inevitably varied from town to town. The first traveling exhibitors had much autonomy with regard to the order of the films shown in their programs. They added title cards in the languages that they saw fit as well as sound or music when they deemed it appropriate. Films often complemented theatrical or technological attractions. These traveling entrepreneurs (as well as those whom they employed as additional entertainment) were often circus managers or performers, illusionists, magicians, or mimes, though some ambitious early filmmakers such as Bolesław Matuszewski arranged projections of their own work. As film historian Stanisław Janicki claims, spaces for their demonstrations “started to sprout like mushrooms after the rain.”12 Until 1903, most of the venues were temporary, but the few permanent optical entertainment centers hinted at the future shape of the industry. As in many of the first demonstrations in Kraków, the traveling exhibitions of “live pictures” were usually additions to other presentations such as live theater or magic lantern shows.13

Generally, exhibitors chose a venue, set up the equipment, collected a small entrance fee from spectators (or demanded a part of the fee collected for entrance into the other parts of the spectacle), projected short films for around twenty minutes, dismantled the equipment, and moved on. Permanent cinemas had yet to be established. However, audiences could count on seeing short films at a few regular venues throughout the region. In Łódź, brothers Władysław and Antoni Krzemiński projected Lumière films at their Gabinet Iluzji and offered a space, called the Bioscop, to traveling vendors in need of a storefront to rent. Also in Łódź, regular projections of the “Edison cinematograph” were held in Helenów, a once-private park that had been offering access to a waterfall, playground, restaurant, candy store, and theater to paying visitors since the late 1880s. In a large concert hall in the park, the first projection using a Lumière apparatus took place on June 11, 1897. Audiences saw half-hour programs consisting of eight Lumière short films featuring coronations, royal parades, and other events from western Europe.14 According to film historians Hanna Krajewska and Stanisław Janicki, a locale for motion picture demonstrations might have been opened in a former restaurant at 120 Piotrkowska Street in Łódź in 1899.15

In Poznań, exhibitors regularly held projections at a popular restaurant owned by Leon Mettler. A successful entrepreneur, Franciszek Józef Oeser, opened the first storefront cinema in L’viv, the Teatr Elektryczny. According to Urbańczyk, Kraków, too, had a Teatr Elektryczny that advertised the novelty of electricity along with cinema as late as the summer of 1905, long after electricity had ceased to be a revelation in many European cities. It announced, “Electric people and electric animals! Tigers, lions, elephants! Everything that lives fights on the electric canvas. People walk and dance. Director Oeser transforms into an electric person on the screen in front of the public’s eyes!”16

Władysław and Antoni Krzemiński ran a permanent cinema at 4 Nowy Rynek Street in Łódź, which held forty-minute projections of short film programs from 1901 until 1903. Teatr żywych fotografii, as they called it, was equipped with an imported projector from Paris. Krajewska describes it as a three-room space—with an entry room, viewing room, and projection room—on the first floor of a building next to a candy store. The entry room, adorned with stereoscopes, functioned as both ticket booth and waiting room. The viewing room held thirty seats (priced according to proximity to the screen) and standing room for sixty, though twice this number generally crowded into it.17

Within a decade, almost every major city in the region had a permanent motion picture theater. The extravagant, Secession-style Teatr Elizeum-Palais d’Illusion in Warsaw, with room for four hundred people, was one such venue. Its repertoire included films by the first local filmmaker, Kazimierz Prószyński, in 1902. According to film historians Małgorzata Hendrykowska and Marek Hendrykowski, restaurateur Mettler dedicated one of his properties in the so-called Promenade Park in Poznań to motion picture projections beginning in December 1903.18 Permanent motion picture theaters were opened in Kraków and L’viv in 1906; in Toruń and Vilnius in 1907; in Bydgoszcz, Częstochowa, and Lublin in 1908; in Przemyśl in 1910; and in Rzeszów and Tarnów in 1911, although cinema in the partitions remained a predominately outdoor event for several more years.19

Small, permanent theaters specialized not only in motion pictures but also in vaudeville, cabaret, and other popular forms of entertainment. Only the largest cities could support extravagant th...